Review by Frank Plowright

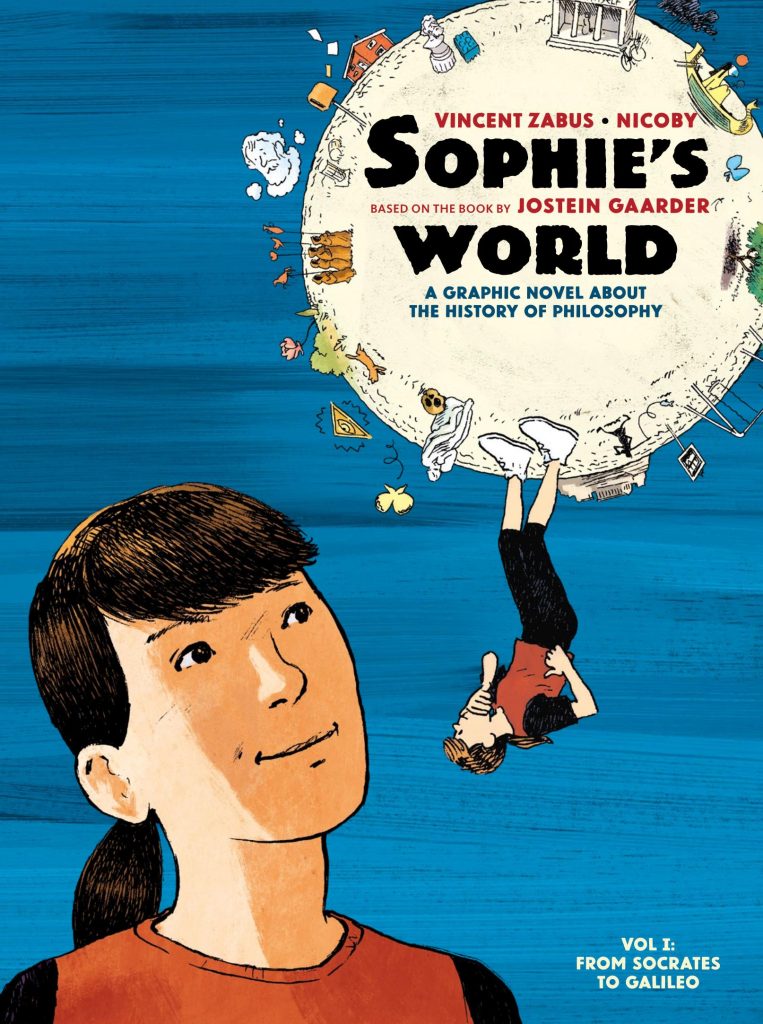

Jostein Gaarder’s Sophie’s World has been translated into 59 languages since its 1991 publication, which is a major success by any standards, never mind for a novel by an author largely unknown outside Norway beforehand. Perhaps a graphic novel version was therefore overdue.

Sophie Amundson is a teenager concerned about climate change who returns home one day to find an envelope addressed to her. Within is a card asking “Who Are You?” She considers the question and discovers another envelope, and so begins her mysterious course in philosophical history. Gaarder follows the Bertrand Russell principle of a philosopher becoming such by asking questions, so an early chapter investigates the myths that sprung up among the first communities to explain the changing seasons or nightfall, and the rituals that sprang from spreading belief.

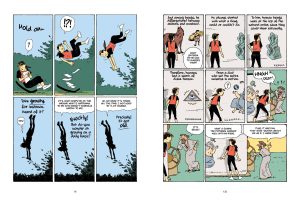

Despite formulating thought being fundamental to the way we live, philosophy remains a dry subject to many, something Gaarder understands. Via the creative adaption team of Vincent Zabus and Nicoby (Nicolas Bidet) he transmits thoughts and ideas in brief snippets, accompanied by funny illustrations that hold the attention. Nicoby’s cartooning is important in giving form to what would otherwise just be description, the old adage of how many words a picture is worth coming into play. One example of how effective this is occurs during Sophie’s tour of ancient Greece, and Nicoby ensures there’s always something visually stimulating on even pages conveying more difficult ideas.

Sophie keeps coming back to her climate concerns, angry that people know there’s a problem, yet nothing is done. It’s distressing to note how little progress has been made in that respect in the 31 years between Gaarder’s novel and the English graphic novel edition. At the same time there’s the mystery of just who’s taken upon themselves to educate Sophie, and why.

As a primary object of philosophy is to have people think for themselves the thoughts of highly regarded philosophers are presented, generally by versions of themselves, and considered. Science has proved some of their conclusions wrong, while others remain valid, and Sophie learns the meanings of terms applied to primary schools of philosophy are now different, and how philosophy and religion intersect. That’s mainly in terms of Christian religion, and if the lessons imparted until the halfway point ending this volume engender anything it ought to be a tendency to question any presentation.

While the cartooning is plain and open, Sophie’s World is a densely packed book, offering a lot to take in, but consistently engaging as it does so. Sophie determining she’s a fictional character and escaping predestination provides a natural break point and leads into From Descartes to the Present Day.