Review by Cefn Ridout

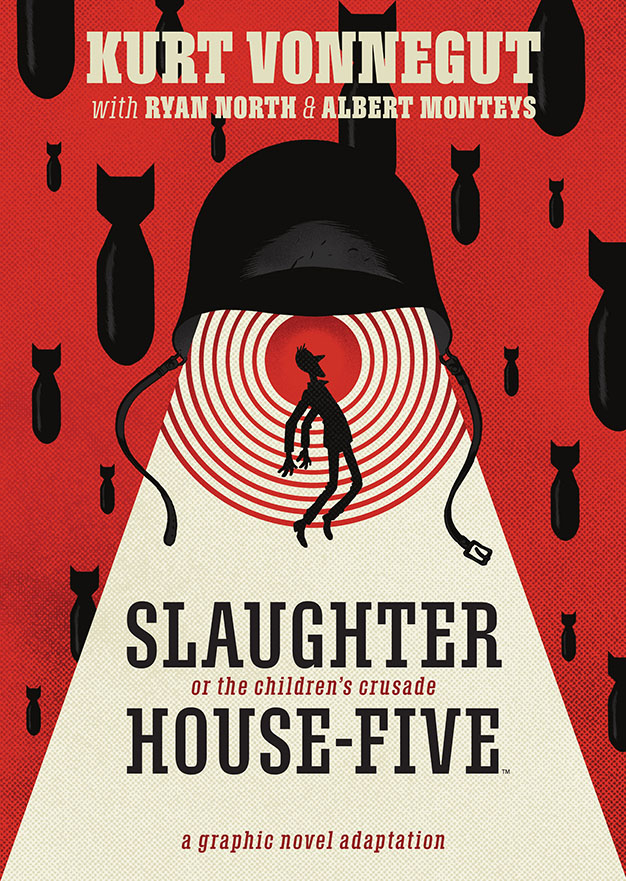

Listen, Kurt Vonnegut has come unstuck in time. Indeed, he seems to be enjoying a (Tralfamadorian) moment. Between the 50th anniversary of Slaughterhouse-Five and the centenary of Vonnegut’s birth appeared the first graphic novel adaptation of his semi-autobiographical, anti-war masterpiece. Taking their cue from Vonnegut’s own high-wire performance, writer Ryan North and artist Albert Monteys fashion a fresh, fearless work respecting and reinvigorating the source material.

Slaughterhouse-Five finds Billy Pilgrim, a 21 year-old prisoner of war, in Dresden on February 13, 1945 when Allied forces firebomb the city. Nearly 25,000 people are killed and the historic town is levelled. Billy, his fellow POWs and their Nazi guards survive by sheltering in the basement of a disused abattoir: Slaughterhouse Five.

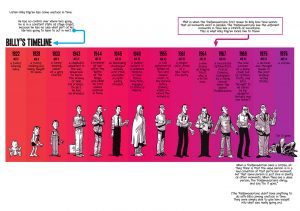

Billy is also temporally untethered. He flits randomly between pivotal moments in his life: a 26 year-old PTSD patient in a veterans hospital, a 54 year-old just-assassinated corpse, and a successful 45 year-old optometrist and family man abducted by aliens from the planet Talfamadore for their zoo. The Tralfamadorians, who experience reality in four dimensions, reveal the true nature of time, that all moments – past, present and future – exist in parallel and that Billy has somehow become “unstuck in time”. The deterministic extraterrestrials also explain how they will accidentally (and always) destroy the universe, accepting the inevitable with the stoic refrain, “So it goes.”

Like Billy, Vonnegut was a young prisoner of war in WWII who witnessed Dresden’s devastation. A pacifist, Vonnegut shunned glorifying the war, acknowledging the “boys” who fought for their country in the title Slaughterhouse-Five or The Children’s Crusade. An instant bestseller, it also attracted outrage and censorship for its irreverence, vulgarity and heresy. Perfect ingredients, some might argue, for comics, especially during heightened anxiety over the Vietnam War, when underground comix had found a receptive audience among draft-age readers.

Yet it’s taken fifty years to adapt the much-loved classic. North and Monteys rise to the challenge with great sympathy, flair and economy, capturing much of the novel’s absurdist drive, fierce humanity and chronological slapstick. The time-tripping storytelling is ideal for the comics medium, and the creators rapidly explore the narrative possibilities. From jump cuts, freeze frames and flashbacks to timelines, gag strips and cut-outs, the restlessly inventive North and Monteys stay true to the spirit and, largely, structure of the original.

Standout sequences include a four-dimensional Tralfamadorian book imagined as a series of surreal, disconnected images; a US bombing raid movingly told through reverse storyboards and The Gospel from Outer Space by Billy’s favourite failed pulp auteur, Kilgore Trout, fittingly recreated as a 1950s science-fiction, comic parable. North and Monteys also bring quiet tenderness to Billy’s last moments with his dying mother and stark satire to the figure of Howard Campbell Jr., Vonnegut’s pantomime patriot disseminating distorted home truths to his captive POW audience. Monteys’ clean, expressive cartooning and vivid colour palette effortlessly complement North’s smart, funny and nuanced script.

For all its many pleasures, the adaptation lacks the novel’s bitter irony and “moral clarity”, in the words of The New York Times. It lacks the edge in Vonnegut’s voice. Slaughterhouse-Five was, among other things, an act of creative salvation, an acceptance of survivor’s guilt, so it’s hardly surprising the intensely personal perspective is absent from the graphic novel.

That said, North and Monteys readily embrace Vonnegut’s belief that humour doesn’t undercut the horror of war, it underscores it. Even as the mood darkens, both versions retain an exuberant, comedic pulse, frustrating those who feel the subject should be treated solemnly. Yet these qualities are intrinsic to life, so making them central conveys the depth of the tragedy. So it goes.