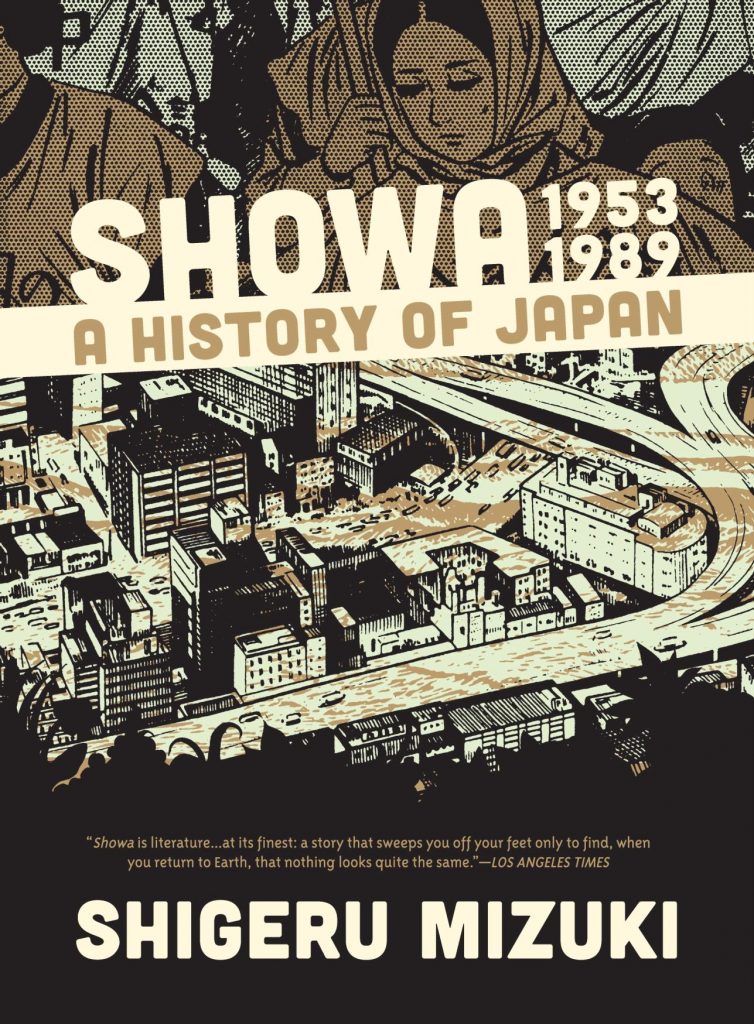

Review by Karl Verhoven

Shigeru Mizuki spent three volumes detailing the first 27 years of his life running parallel with Japanese history, and here supplies the subsequent 36 in just shy of six hundred pages. That’s achieved because over time both Japan and Mizuki radically changed, settled down and became prosperous. In acknowledgement of this parallel rise Mizuki changes format and begins sifting his own story into wider circumstances instead of partitioning them. Frederik L. Schodt’s introduction notes Japan’s view of global events often differing from the outside perception, and Mizuki supplies this while highlighting shocking incidents unknown outside Japan. These are often fascinating, belying the perception of Japanese corporate dominance and overseas export success being one smooth ride. Frequent violent tension is recalled, both via disgruntled individuals and organised radical groups, and Mizuki catalogues scandals and atrocities, seeing them as significant during social confusion. As previously, copious footnotes and references to the glossary at the end explain what English readers may not understand.

In 1953 Mizuki was introduced to a manga publisher, but although talented and confident in his own abilities, he barely made a living, nicely represented by a scene of pawning his shoes, and then noting he only retrieved them three years later. It was a further decade before he could claim success, one subsequent chapter titled ‘A Life of Extreme Poverty’, echoing the opening volume title of Robert Crumb’s collected output, The Early Years of Bitter Struggle. At times it seems the good fortune ensuring Mizuki’s wartime survival on so many occasions is spooling out in reverse. Other aspects of his life are only half-mentioned, his marriage a strange affair as portrayed here.

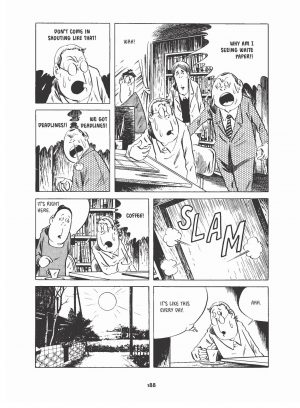

By the mid-1960s Mizuki is finally comfortable, but success brings pressure from publishers for more and more work, which becomes its own problem. Mizuki again drops a tragically appropriate signifier of his life: “There was a beautiful tree I could see from my window. I allowed myself to look at it twice a day. That was my only break”. It’s heart-rending, and the consequences of that workrate are inevitable. Assistants help, but also generate tensions, as detailed in a chapter about their squabbles, with the hilarious and sad problems of another assistant spotlighted later.

Mizuki isn’t spiritual in the conventional sense, but as seen in previous volumes, he’s open to beliefs beyond the scientifically proven, in his case personified by monster ghosts of Japanese myth. They feature on a tomb he constructs, simultaneously head-shakingly excessive and respectful. Inexplicable events occur several times, and a whimsical chapter about afterlife insurance seems to represent a lost period, with 1971 a turning point. Mizuki returns to the people who befriended him in Papua New Guinea during World War II (see 1944-1953) and again finds a form of temporary peace among them.

When he completed this volume in 1989 Mizuki didn’t imagine he’d live much longer, although he did, another 27 years, and the freedom of that generates an honesty the younger creator might have suppressed. He’s humane, his intelligent opinions are enlightening, he’s scathing about patriotism and duty being more important than individual lives, and brutal about the manga industry in which he’s such a success. “Being not unhappy was about the best you could hope for” is no ringing endorsement of his career, yet looking at some of his inconceivably detailed cityscapes it’s easy to imagine him becoming lost in drawing them as deadlines float away. Given the density, the understanding and the astounding portrayal via Mizuki’s mixture of simple cartooning accompanying rich backgrounds, there’s surely no better way to absorb post-war Japanese history. Plus, this edition restores over sixty pages of Mizuki’s colour paintings.