Review by Karl Verhoven

This third adaptation of the Sherlock series introduced Moriarty to his 21st century world. It begins with a bored Sherlock, a Sherlock so bored he’s even read Watson’s blog about their first case (see A Study in Pink) and takes issue with his presentation of Sherlock lacking elementary knowledge most know: “Oh, you meant spectacularly ignorant in a nice way”. Despite Sherlock’s annoyance, the blog is attracting attention, and has one reader using it to challenge him.

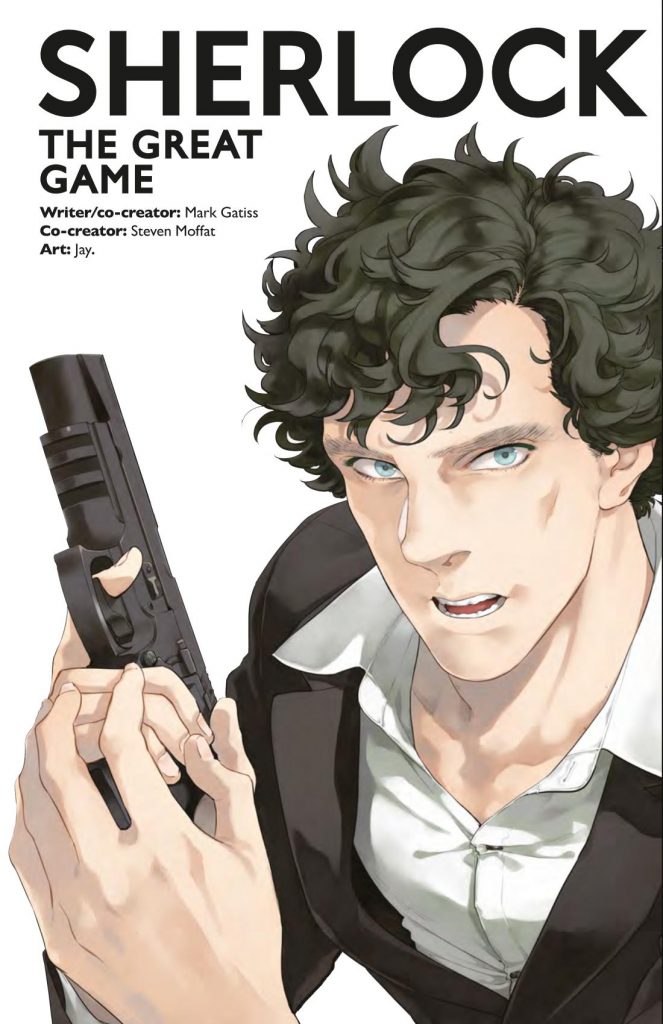

After the slight dip for The Blind Banker, both manga adapter Jay and the script he’s adapting from TV show writer Mark Gatiss are back to form. The script forces Jay to be more inventive with his art as it can’t be adapted using figures alone, and while the backgrounds aren’t as richly presented as TV, there are far more of them in which Holmes, Watson and other cast members are implanted. As previously, Jay captures a likeness for Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock extremely well, incorporated into a fluid and simple art style. He has greater trouble with other cast members. As before, Martin Freeman’s Watson is extrapolated rather than directly drawn, but there are also problems with Andrew Scott’s Moriarty where visual reference is more obvious

Gatiss’ plot is consistently inventive and surprising, dazzling with ingenuity and locked together tightly until a thrilling finale. It’s a very self-aware piece again wearing its cleverness on its metaphorical sleeve, but Sherlock’s primary enemy is nothing if not self-aware and drawn to a grand gesture, and a tension is continually implanted by means of deadlines with lives at stake. It’s never stated in the series or here that Sherlock is somewhere on the autistic scale, but it’s a deliberate intention of this modern update, with his concern for other people and their well being almost non-existent except as abstracts. “Will caring about them help save them?”, he asks. An exception is if people can interest him somehow, and interesting him invariably involves challenging his intellect, posing a puzzle. The plot for The Great Game emphasises this superbly. Sherlock’s callous attitude to victims is because he’s entirely occupied with solving a puzzle, to which they’re secondary, and with the series of events that play out during The Great Game he’s continually challenged and continually stimulated.

A constant stream of impossible puzzles dazzlingly solved gives the story pace and density, and for the prolonged finale Jay takes a full 25 pages to eke out the tension, remaining faithful to the source. This faithfulness extends to there being no definitive ending, events cutting off on a cliffhanger as they did on the TV show. Perhaps better would have been incorporating the conclusion that started season two, particularly as while Jay now intends to adapt that season also, there will have been at least a five year gap when it’s published.

Steven Moffat is also cover credited, but the internal credits list Gatiss as sole writer. The Great Game can also be experienced combined with the previous two Sherlock adaptations in a slipcased box set titled The Complete Season One Manga.