Review by Frank Plowright

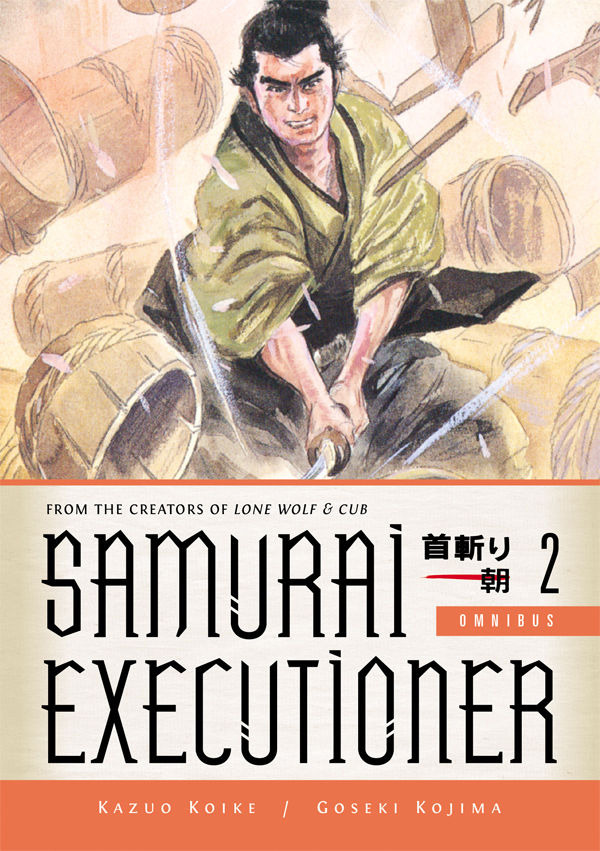

A second larger than previously presented collection of Samurai Executioner follows the pattern of the first other than Kazuo Koike now feeling he can write longer stories when needed. He has an enthusiast’s passion for the mid-Edo era of Japanese history, corresponding to some time in in the 1700s, and elements of his tales frequently feature an obscure piece of social convention that he’s researched. This is slightly more obvious than in the first collection because there’s a greater emphasis on the recent past of those being presented to executioner Yamada Asaemon. In some tales he barely features other than as the inevitable end to events.

Koike is strong on ensuring we have some sympathy for the criminals seen, delivering a relatively complete picture explaining their circumstances, and what might have pushed them into crime, or at least the era’s concept of it. By our standards injustice frequently occurs, and a story about how a condemned woman can delay her execution, although one of the weaker selections, is a horrific condemnation of the practices of the time. However, some of the soon to be deceased are plain mad.

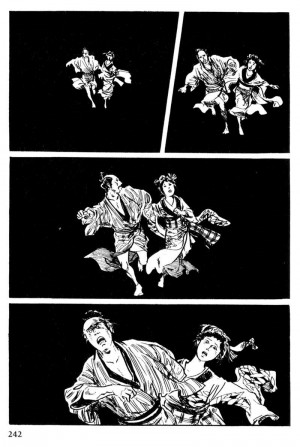

There are pros and cons to Goseki Kojima’s art. There are certainly no quibbles about the quality of his action sequences, or his elegant country locations, and he maintains a grubby atmosphere suitable for the type of historical pulp stories being told. He can also supply very cinematic panels at times, such as the sample art of two figures running away from someone and toward the reader, framed in black ink as they move closer. Balanced against that, his people can be hard to distinguish from one another, having very similar features. One improvement of these larger sized editions is that the art has a far greater clarity, losing the consistent smudged quality that plagued the pocket sized versions. The only smudginess is deliberate shading, which is consistent with the tone.

These stories were created in the 1970s, but the craftsmanship and period setting means they remain contemporary, and several issues still plague today’s society, one a beancounter unable to view anything other than direct cost and expense, never mind the mid-term consequences. Koike also relishes what could be considered sordid activities, occasionally to highlight hypocrisy, and this is explicitly illustrated by Kojima, as are the effects of violence. It supplies a lurid quality to a selection of stories always heavy on human interest, in which some characters recur. Not everything works, a story occasionally not clarifying the point at issue, and others just dragging on too long. It’s a fine balance, though, as the tale of Tōgane Yojirō, an over-zealous policeman, benefits immensely from time devoted to seeing him in action, and contrasting his efficiency with his coarse manner.

If the smaller editions are preferable, these stories feature in The Hell Stick, Portrait of Death, and Ten Fingers, One Life.