Review by Graham Johnstone

‘Confidential’ is an overused title device, but justified for this biography of Jackson Pollock, as it references the CIA files on the painter. As the book explains, an early strategy of the USA’s Central Intelligence Agency was to promote American Abstract Expressionists like Pollock as a weapon in the Cold War.

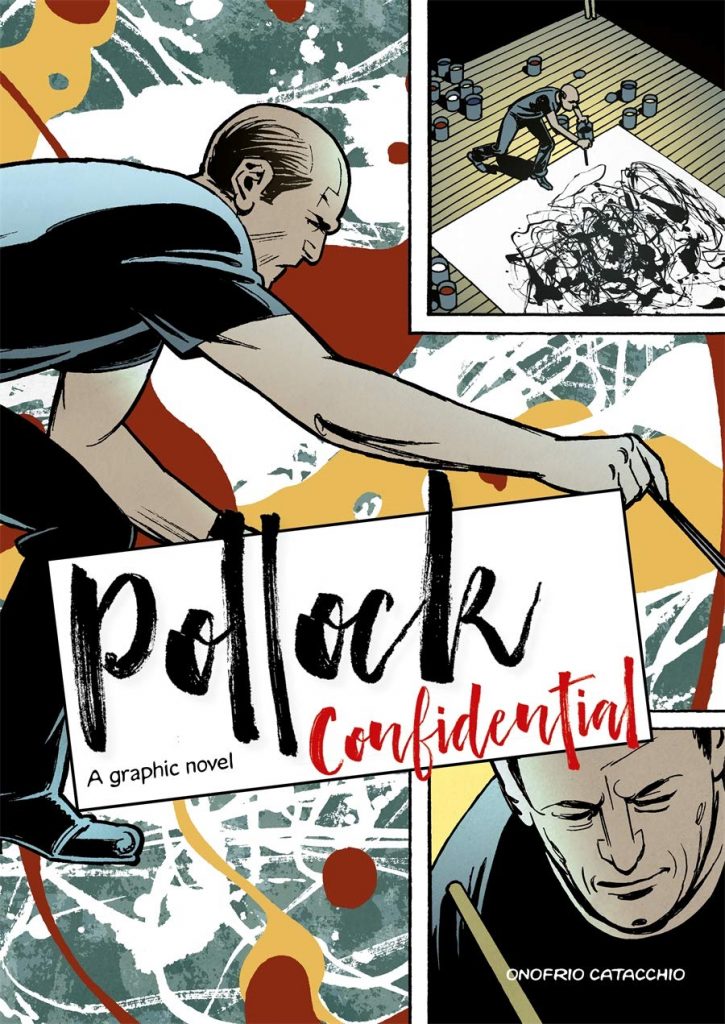

In the emerging genre of graphic biographies of artists, most have been highly fictionalised, dramatising their subjects’ lives with invented scenes and dialogue, in the manner of cinematic biopics. In contrast, Pollock Confidential uses various modes of documentary film. A fictional framing device introduces former Agent Adkins as the documentary’s narrator. He introduces the reader to what the CIA called ‘Operation Long Leash’, and to his allocated subject – Pollock. Next, Adkins follows the Pollocks’ relocation to coastal Long Island, connives a meeting and befriends them, thus the ‘filmmaker’ enters the film in the manner of participatory documentary.

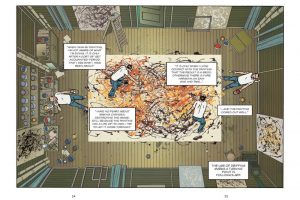

We see Pollock only through specific sources, i.e. the CIA file, Adkins’ direct contact, then public sources, including quoted statements, and documentary footage of Pollock painting. These limited sources nevertheless enable a well-structured, and economical portrait of Pollock. Adkins reports on the artist’s methods: he’s started working in his barn where he can lay vast canvasses on the floor. “The dripping colours weave together to the rhythm of Jackson’s movements,” his report reads, “as he shuffles along the edges of the painting”. Some key scenes can be usefully compared with Ed Harris’ biopic Pollock. While Jackson’s impulsive moment at Peggy Guggenheim’s party lacks the film’s depiction of the heiress’ poised response, however, artist Onofrio Catacchio’s night-time setting of future wife Lee Krassner’s first visit to Pollock, better suggests her sexual intent. Among the fascinating details revealed are Pollock’s inspiration from Native American sand painting, and his support from Mondrian – the most apparently opposite of abstract painters. The implied non-fiction contract prevents Catacchio imagining Pollock’s private thoughts on, for example, his alcoholism, but offers instead a symbolic image of the painter crawling in a sea of empties.

Artist biographies, notably Rembrandt and Pablo channel their subjects’ visual style – that’s not viable with Pollock’s pure abstraction, though Catacchio goes to the other extreme, with pristine illustration, and tonal fades that evoke photography, and so documentary film. Further cinematic effects include dissolves between times within the same shot, plus montage and time-lapse (pictured) spreads of Pollock painting. Another cinematic device deftly applied is insert shots from outside the story world: a revealing photo with other-woman Ruth; a map of Western state boundaries superimposed on a corresponding landscape; and symbolic images, like grappling Soviet and American flags. The motif of Pollock’s dribbled paint swirls is repeated hypnotically, building up to its powerful use in the climactic scenes that evoke his state of mind as he drives, then the design of a life-flashing-before the-eyes montage. Deft use of pacing, composition and scale, further add to a powerfully visual climax.

Given it’s foregrounding in the title and ‘angle’, more on the CIA element would have been welcome, The reveal of their engineering of a Life magazine feature is fascinating, however, what’s lacking is some retrospective consideration of the ethics and impact of the CIA intervention. For example, did the CIA’s championing of Abstraction railroad American art, and were art patrons further enriched by receiving state funds to buy paintings, now ‘worth’ hundreds of millions? The framing sequence with Adkins looking back from the 1970s is an opportunity sadly missed.

Ultimately though, as a biography of one painter, Pollock Confidential convincingly delivers.