Review by Frank Plowright

In 1980 Dan Millman published the semi-autobiographical novel Way of the Peaceful Warrior, which floundered until reissued in 1984, after which he was able to switch careers from being a college physical education coach to a presenter of seminars encouraging human potential. His career really took off in the 1990s, and Way of the Peaceful Warrior was released as a film in 2007.

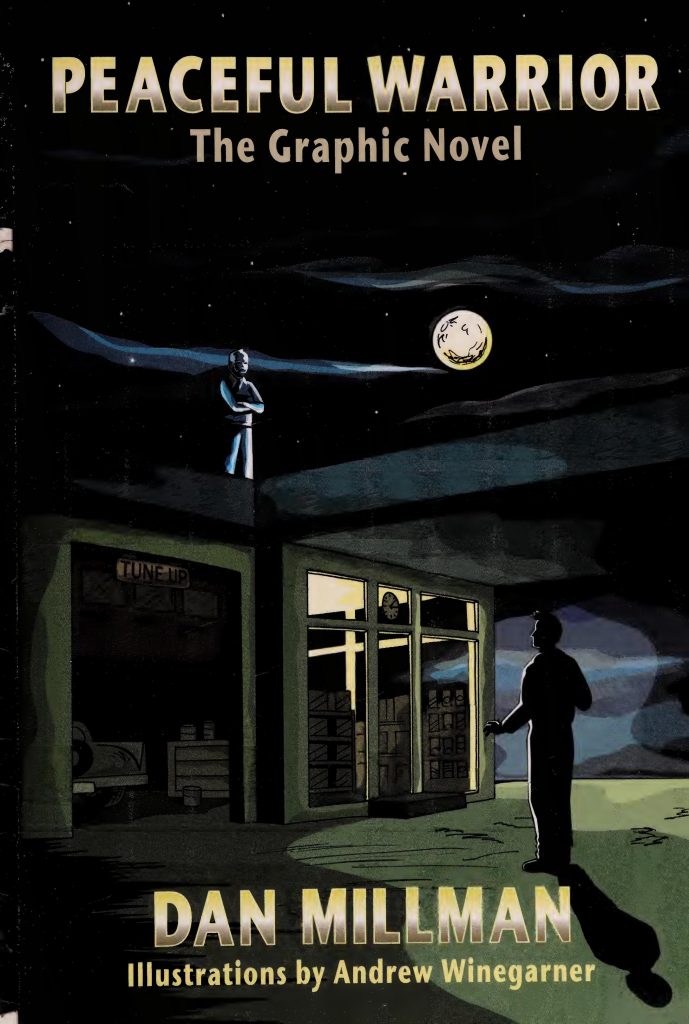

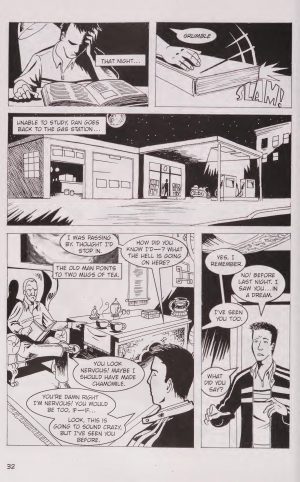

Three years later this graphic novel adaptation arrived, Millman explaining in his introduction that he’d been inspired by comics. His life journey really begins in his late teens. He’s a college gymnast with potential when he meets an enigmatic garage mechanic he calls Socrates, whom he credits with changing his life. Socrates is a provocative pomposity puncher, able to do remarkable things because he’s in touch with his spiritual side, and considers Dan worth training to battle a forthcoming battle against dark, invisible forces. Dan had to take this on trust. So will we. You’ll either believe Millman’s advocation of the peaceful warrior as it spools out over a further 150 pages you’ll succumb to your inner cynic.

Millman has a definite message he wants people to take in, and has a successful track record of promoting that message over numerous follow-up books. It’s strange therefore, that even if he’s commissioning the art himself, his choice of artist is Andrew Winegarner rather than an established comic artist who might have been able to bring some life and emotion to the script. Winegarner’s oddly shaped people and application of superhero exaggeration to what’s supposed to be an autobiography further diminish Millman’s point. If it’s difficult enough to swallow anyway, by the time Winegarner’s drawn it, the impact diminishes further.

A third of the way through, Dan has a life changing experience, and the path he’d plotted for himself appears no longer an option. It’s interesting how beyond mentioning the death of his father, Millman’s life as presented is exclusively one of school, gym training and visits to surrogate father Socrates at the garage. When we see him at home it’s always alone in his room, never interacting with his mother or any other family members he may have, and this is never addressed. Those keen on amateur psychoanalysis of others will have a field day.

In essence the teachings of Socrates, as passed on by Millman involve self-improvement via discipline, dedication, decent diet and the avoidance of what we may enjoy, but we also know isn’t good for us. Socrates supplies other common sense advice such as life not being about success or failure, but about constantly testing limits, yet also displays abilities most humans consider beyond them, but which he believes are attainable by those who dissolve self-imposed limitations. For the final quarter of the book Dan follows the path he believes has been set out for him, the first nine years of that reduced to two pages.

Almost everything Millman wants to pass on is sound advice for healthier living, but often imparted in the tritest terms, credibility damaged with scenes of magical realism that few will ever believe. The counter-argument, difficult to disprove, is that a closed mind is the stumbling block to the path of enlightenment. Most people come across something that helps them in a time of crisis and cling to that, sometimes imparting cosmic significance to random chance, and if it makes them feel better while harming no-one else we should embrace that.