Review by Graham Johnstone

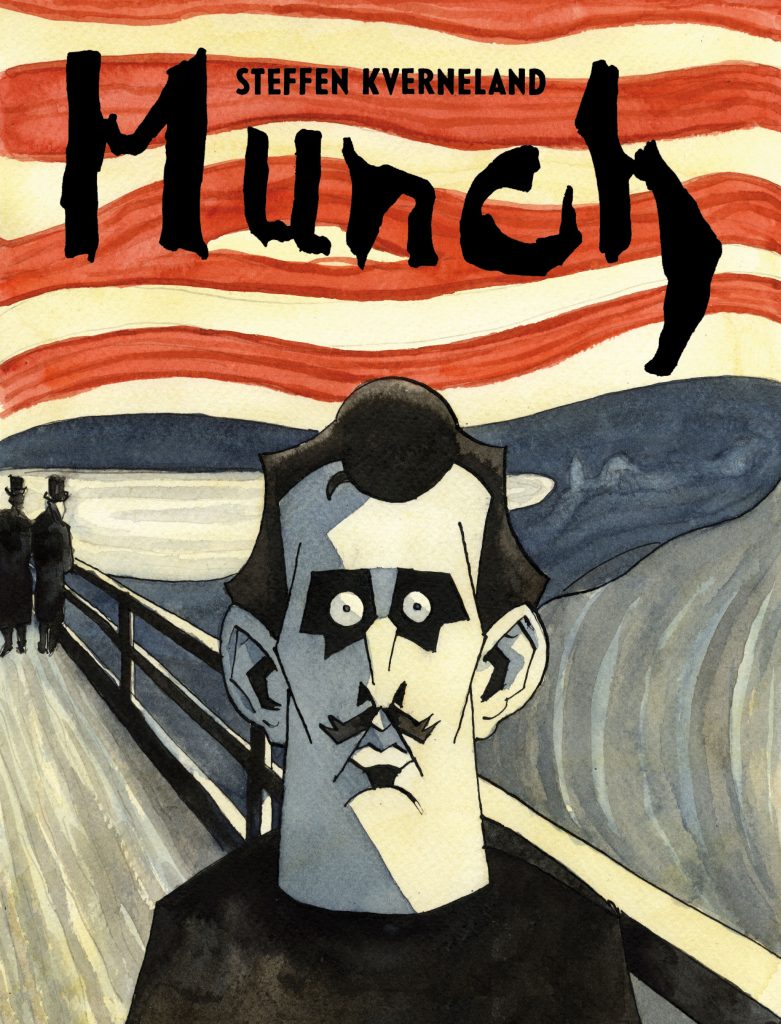

Edvard Munch’s The Scream is a famously expressive image of modern art, so ripe for an exploration of the life that inspired it.

Munch, in English translation, is the fourth in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series, after Vincent, Pablo, and Rembrandt. Like its predecessors, it’s by a European creator acclaimed at home, but new to the anglophone world.

In his native Norway, the young Steffen Kverneland was respected enough to secure a weekly newspaper page for ‘Classics Amputated’, his irreverent takes on classic literature. For The Divine Comedy, for example, he portrayed Danté and Virgil as latter day Italian ‘bards’ Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. He’d also tackled biography with Olaf G, about the Norwegian illustrator. So it seems inevitable that he turned his talents to his nation’s most famous artist, and also that the result would be no straightforward illustrated chronology.

Kverneland sets out his stall with an introduction in comics form, featuring himself and sometime collaborator Lars Fiske. He commits to using a “collage of pure quotes… letting the sources speak for themselves and [refusing to] add or rewrite anything.” Impossible with, say, Rembrandt, it works with Munch because of the abundance of primary sources. Collage is a Modernist invention, and the multiple viewpoints fit that movement’s rejection of moral and perceptual certainties. To avoid muddying the ‘reporting’ with ‘editorial comment’, he inserts the latter in the form of continuing discussions with Fiske as they visit key locations.

Kverneland takes us through the tragedies that shaped the artist. His childhood was defined by sickness, and the death of his mother – causing his distraught father to disappear into the bible. He’d obsessively revisit this in his paintings and prints, but also powerfully, in his journals: “My mother gave me … Consumption – my father … insanity”.

But this is no dry account – it’s visually engaging, and the ‘misery lit’ elements are balanced with humour. When three gentlemen enter Munch’s breakthrough exhibition, their hats rise off their heads in unison. Then their thought bubbles show a monkey producing the paintings, then a baby and a mentally ill person – the final result a steaming turd.

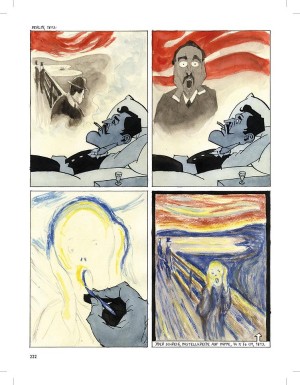

Munch’s journal entries on reactions to the exhibition are depicted in more contemplative fashion with a sequence of him lying on his bed: he smokes, the cigarette burns down, he brandishes a review. There’s a glass and bottle we never see him touch, yet the glass empties and is replenished. However, when he marvels at mere paint causing such unrest, it seems jarringly redundant that he’s suddenly brandishing a well-used tube.

A dizzying array of visual styles identify different strands. His 1890s heyday is drawn in an angular cartoon style. It’s less like the smooth curves of Munch than the German Expressionism he’d inspire, yet still redolent of his heady life in Berlin: the intellectual excitement and turbulent relationships. Other scenes drawn more like Munch focus on his art and direct inspirations. A pivotal romantic encounter at his iconic beach setting inspires his various Madonnas and female nudes filled with loss and hurt. Earlier incidents are in the sepia of the first photographs, but rendered with the vagueness of memory. Later life reflections are signalled by portraits of the older Munch, and rendered realistically in grey washes. Finally, the scenes with Kverneland himself are more documentary, with photographs, including the trademark curved coastline, and posing in situ for The Scream.

The result is a comprehensive and insightful biography of Munch, plus a fascinating record of Kverneland’s own intellectual and creative journey. Less accessible than Vincent or Rembrandt, Munch is not an easy read, but it is a rewarding one.