Review by Graham Johnstone

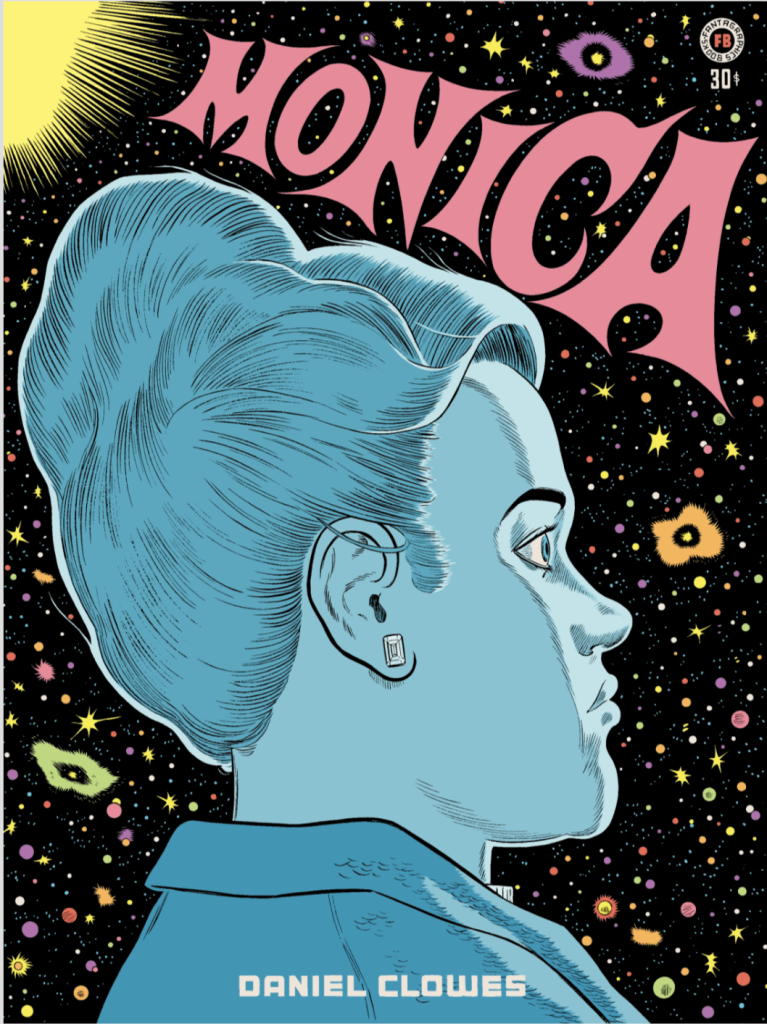

Daniel Clowes made his name with anthology series Eightball, and the contents page of Monica suggests a return to that form. A series of titles in contrasting lettering evoke different genres and styles: war story, horror, flower-power era romance, and so on. However, reading through them, connections emerge forming an ambitious composite novel.

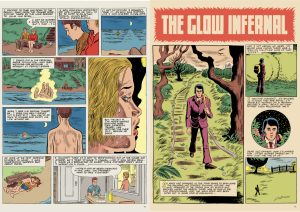

Opener ‘Foxhole’ has G.I. Johnny, thinking of his fiancée back home. Next episode, ’Pretty Penny’, shows her having fun without him, and the subsequent unplanned birth of daughter Monica. This, it emerges, is narrated by Monica herself, following a late-life quest for her roots, and further episodes revisit her, decades apart. Interrupting these are two genre interludes. ‘The Incident’ shows Johnny, now a detective, bringing home a missing adolescent, so triggering thoughts of his own younger years, and of Penny. ‘The Glow Infernal’ mirrors themes, and provides a supernatural mirror to the main story, but has no explicit overlaps, leaving readers to wonder how it feeds into the overall story…

Clowes’ early graphic novels were socio-cultural travelogues as much as narratives, and that fascination endures. ’Foxhole’, for example shows no Vietnam War action, instead concentrating on the grunts’ musings on their situation and prospects back home. In a novel spanning Monica’s lifetime (and his own), Clowes conjures each era with deftly placed cultural details like ‘the Pill’, Walkman cassette players, internet ‘fluff pieces’, and personal ‘brands’, so building a collective life-story of Generation X.

This rich story-world is experienced through a relatable protagonist and compelling story – Monica and the quest for her roots. Her narration vividly illuminates herself and others. It often seems to tell too much, which disguises significant omissions. Clowes typically shuns action heroes, preferring alienated, ambivalent, anti-heroes. However, Monica is plausibly fearless in pursuing her quest to a high stakes conclusion.

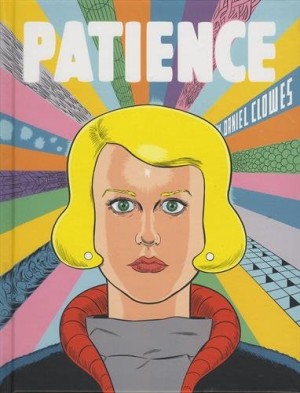

The art, like predecessor Patience, lacks the nervy energy, and pristine rendering of his earlier work. However, the mature Clowes impresses with understated craft. He packs a lot into these hundred-odd, album-sized pages, notably distilling flashbacks into elegant single panels. He designs subtly distinctive faces, recognisable across decades and generations, and his sketchy backgrounds conjure scenes and atmospheres without stealing focus, and comics’ traditional limited palette of flat colours is applied. However, even overlaid on ‘paper’ tints the colours look less like vintage newsprint comics than their typically over-saturated ‘restored’ forms. That’s presumably deliberate – all part of Clowes’ ironic, Generation X, cool. Between art and colour, few pages dazzle, but together they carry a rich and intricate story, guiding us through the parade of people and places.

Monica is generally chronological, but non-continuous, and from multiple perspectives. Such fragmentary composite novels are not new, with Jennifer Egan’s 2011 Pulitzer winning A Visit from the Goon Squad a possible inspiration. Clowes similarly implies a larger story across the fragments, and does so using his chosen form and its classic genres. He weaves his strands artfully together, misdirecting expectations, and delivering some astounding blindsides. If the art on its own never dazzles, it delivers a story that absolutely does. A final revelation, absent from Monica’s unreliable account, may be staring out of the pages, and the ending will send many readers right back to the start, in search of such missed clues.

Clowes’ interviews about Monica indicate a creative reimagining of both his own upbringing, and the world’s woes while he wrote it. This adds further depth to ‘Monica’s’ story and the apocalyptic portents, making this Clowes’ best book yet.