Review by Ian Keogh

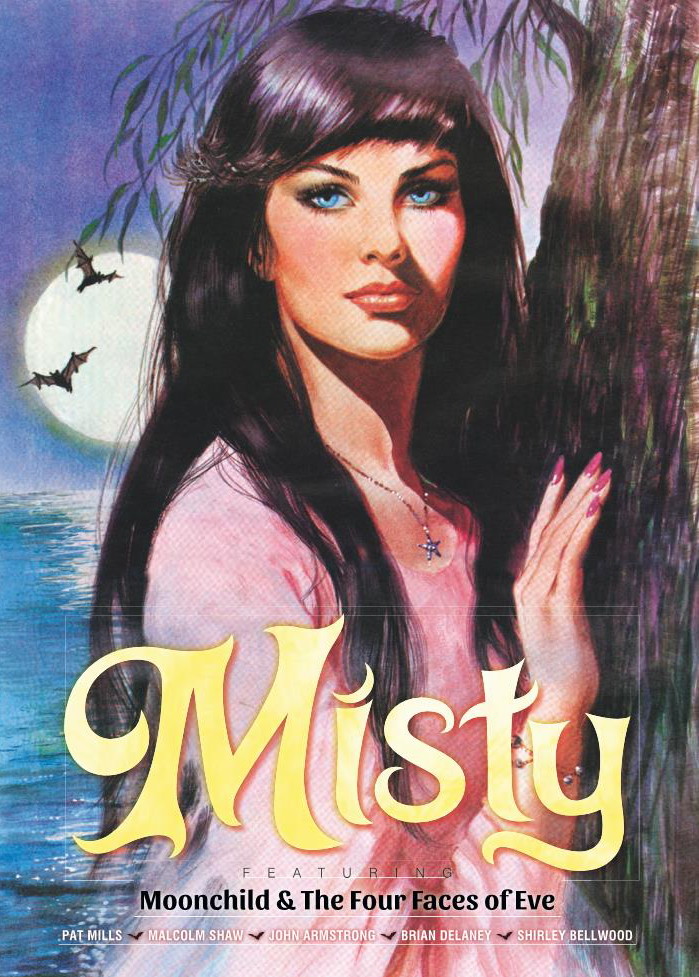

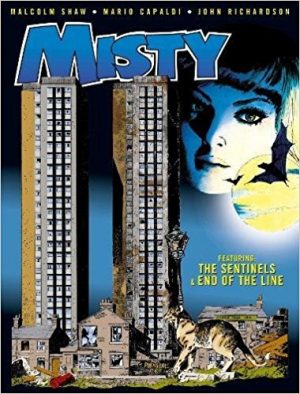

British girls’ comics in the 1970s were still recycling the stories and attitudes of the 1950s. Wholesome middle class white girls were dragged through serialised and formulaic soap opera plots where a bit of grit, elbow grease and/or stiff upper lip eventually won the day. Ballet dancers and ponies often featured, sometimes together. Having spent a good five years revolutionising weekly boys’ comics with Action, then 2000AD, Pat Mills turned his attention to their opposite. His intention was to fuse the supernatural with a look at modern, less privileged society, and Misty presents two complete stories originally serialised on a weekly basis.

As Mills notes in his introduction, things didn’t work out and he quit, only to return when Misty was about to launch, discovering, as he puts it, “punches were pulled”. He still recommends the art. It’s John Armstrong who illustrates the opening ‘Moonchild’, thirteen episodes of gothic suspense. Armstrong’s visual characterisation is superb. He creates an innocent and appealing Rosemary, consistently wide-eyed and troubled, and matches this with fine designs for the other major players, the school bully and Rosemary’s mother.

Mills begins ‘Moonchild’ well, with Rosemary’s mother on trial for cruelty to her daughter, then leads us into Rosemary’s life after the acquittal. She’s tormented at school, yet assorted strange events occur, and her tormentors are victims of accidents. Can she really be a witch? Mills toys a little with the tropes, but also sticks quite closely to what was acceptable for the era, and the strip never achieves the unsettling mood achieved by its influence, the film Carrie, until the finale. There are some pure Mills touches, particularly the unrepentant school bully, and a late arrival to the plot, while the resolutely 1970s comprehensive school was a step forward from girls’ comics usually featuring more privileged settings. Since then generations have been raised on Grange Hill and East Enders is Britain’s favourite soap opera, and while the illustration throughout is excellent, the progress has been overtaken by time.

‘The Four Faces of Eve’ is the work of Malcolm Shaw and Brian Delaney, the title and inspiration taken from the 1957 movie about what’s now considered disassociative personality disorder, and is altogether more successful. Eve awakens in hospital having undergone some procedure unexplained by her strangely distant parents. She dreams of a plane crash, is told of a fire at her house, and wonders why there are bars on the window of her ward, and security men with dogs patrolling outside.

Shaw’s writing is very skilled, unpredictable and impressively unconventional. He maintains a persistent tension through everyday objects seemingly possessing a sinister significance and reveals clues through the oddest of discoveries, a tax form, a stray fingerprint after a robbery and an encounter with a fortune teller. It coalesces for an extremely addictive brew, and is well reeled out episodically. Delaney’s fine line and appealing characterisation is a winning combination, and everything leads to a suitably perverse twist and thrilling conclusion.

When originally published both stories were specifically targeted at young girls, but it’s to be hoped we’ve moved beyond narrow gender stereotyping. The social realism of the times now passes off the stories as well researched period pieces, so there’s much to be enjoyed by the most robust of young gentlemen.