Review by Graham Johnstone

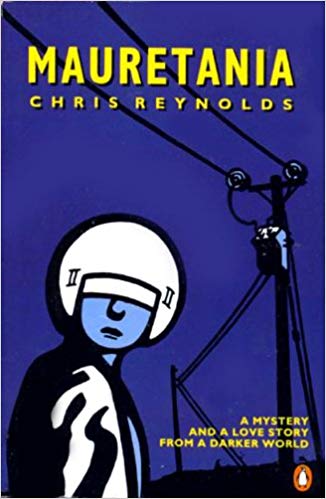

1990’s Mauretania was the first original graphic novel commissioned by a major British publisher. By then there’d been a media stir around the trade editions of DC’s superheroes-gone-serious Watchmen and Dark Knight, and Love & Rockets had found a niche with hip youngsters, but the mainstream success of Maus was yet to come. The wider book market wasn’t quite ready for graphic novels, or for this still unique, genre-defying work.

Mauretania Comics emerged from the British small press comics scene of the 1980s. Reynolds (and self-publishing partner Paul Harvey) may have taken inspiration from Eddie Campbell’s autobiographical comics, but went in a different direction – apparently drawing on his own experience of contemporary Britain, but exploring this in more oblique and poetic ways. Reynolds is best known for short compressed stories, gathered in Adventures from Mauretania, and more recently The New World. This was, and remains, his only book length work.

Mauretania, the cover tells us, is ‘a darker world’, but it’s almost a genre. Few comics before or since have had such a distinctive mood or approach. Life in what looks like the British Isles, carries on almost as normal, with hints at take-over and management by shadowy forces like Rational Control. Amongst this, Reynolds’ characters try to remember and imagine better pasts and futures.

Susan’s life is going nowhere, so when Fern Ltd closes and she’s out of work, she sees it as an opportunity. This is symbolised by her declining a last lift home, in favour of a walk into a landscape previously seen only from the office window. A new job proves odd – there’s little to do and they’re most interested in quizzing her about her old job. She discovers the company is a front for Rational Control, who are spying on ‘Jimmy’ in the building opposite.

Jimmy is better known as helmeted enigma Monitor (cover image). Other stories refer to his spaceship, but is he here with a purpose, stranded, or just a human dreaming of escape… ? As Rational Control observe him, he observes them. Monitor seems less a man with masterplan, than some zen-like agent provocateur – his oblique interventions provoking decisions and actions by those around him. Rational Control use Susan to find out what Jimmy is doing, through a story of continual reveals and reversals.

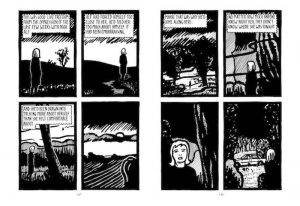

Reynolds essentially created his own genre – his stories have a powerful mood – a nostalgia for a perhaps imaginary past, and a yearning for a better future. There’s definitely something of Franz Kafka in the inscrutability of the social environment. However, in contrast to the latter’s extreme satirical horror, Reynolds presents everything in neutral fashion, leaving the reader to form their own response – a process that continues long after reading the last page.

This is complemented by Reynolds wood-cut style, and simple, iconic drawings. As Scott McCloud would later theorise, such drawings are subjective and universal, so enabling the reader to put themselves in the story. Over this length the art doesn’t sustain the concentrated brilliance of his finest short works, but not much does.

Mauretania, (and Penguin, the esteemed British publisher that commissioned it) were ahead of the market in 1990. Thirty years later, it’s lost none of it’s power, and deserves a much wider audience.

This edition is long out of print, but used copies can still be found. However, the complete contents, along with most of Adventures in Mauretania, and The Dial, are included in the definitive 2018 collection The New World.