Review by Graham Johnstone

Chris Reynolds emerged fully formed in 1986 with the Mauretania Comics anthology. In the wake of Eddie Campbell’s autobiographical naturalism, Reynolds and friends explored personal concerns in more poetic form. A selection are gathered here, with some later companion pieces.

This Mauretania is not a place in Africa. The rolling hills and village streets evoke Britain, perhaps the inter-war years, yet with mysterious additions like The Lighted Cities. Equally, Mauretania is a feeling – a yearning for the absent: distant people or places, a half-forgotten past, or imagined future.

These ‘adventures’ involve no chase sequences or nail-biting moments. Crime and danger form a backdrop for more internal struggles. ‘Whisper in the Shadows’, for example involves the death of a detective, yet omits the central event, focussing instead on a child’s reaction.

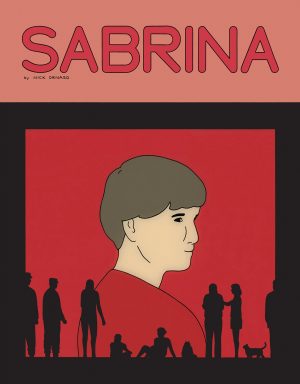

Two-page opener ‘The Lighted Cities’ (pictured) is a highlight. Typically matter of fact narration tells of a couple’s visit to farmer Jack. The first page is pastoral – tractor, cows, ploughed fields, the love of wide open spaces – until the last panel, when Jack casually mentions ‘patrolling for Telmarines’. What? Reynolds doesn’t explain, but thereafter builds a sense of unease – the huge planes flying across three panels, and the chickens that ‘considered the cook house a home’ wandering amongst pots they may end up in. The concluding note of optimism about the Lighted Cities doesn’t quite reassure. It’s a master class in storytelling: understatement, omission, compression, misdirection, and telling details. It also exemplifies Ernest Hemingway’s ‘iceberg theory’ – that an author should know more about the story than they tell the reader.

Reynolds’ art shows a similarly judicious minimalism, well captured in the featured image. His painterly brushwork conveys the landscape, chickens, and aeroplanes with all the detail we need. The best panels, like panel eight of this same page, are masterpieces of elegant simplicity. In a few lines and seemingly effortless dabs of ink he captures the farm, the people, the chickens, and a convincingly retro-futurist car – perfectly angled to both highlight its form, and to point towards departure through the final panel. It’s cast in long shadows, as if by the Lighted Cities in the next and final panel.

Several stories centre on helmeted enigma Monitor. He has a space ship we never see, but which signals his aspiration, and so the bathos of his string of unfulfilling jobs. ‘The Small Mines’ sees him away from home for a Works Fund post as a mine agent. Mines are closing, but aliens run one – not as an invading force but as purchasers of the mineral rights. The mines close and someone who found a new lode ‘next day was found drifting down the river in the ice’. This macro-narrative is revealed as passing details in Monitor’s micro-narrative: his new job, visits from friends, his grandfather’s homey anecdotes, and his journey on the train ‘Enterprise’ where he’s fleeced by a cardsharp before even reaching the affluent south.

These stories were born out of 1980s Britain, and it’s all there if you look: state support replaced by global capitalism; the financial disparity between capital and regions; the shift from welfare to workfare; itinerant youth chasing work; and over it all, the cold-war threat of armageddon. These stories reflect their time, but reach beyond it – readers will find their own meanings. Thirty years on we may be approaching the end of that era, with the same mix of hope and dread as in these still beautiful, still unique pages.

More of Reynolds work, including longer stories can be found in Mauretania and The Dial, with most now collected in The New World.