Review by Frank Plowright

March is titled after a defining period, both in American history, and the life of Congressman John Lewis, a primary organiser of 1963’s March on Washington. The opening volume only touched on the march in passing, being an autobiographical recollection of Lewis’ early years and events coalescing to cement his views on life.

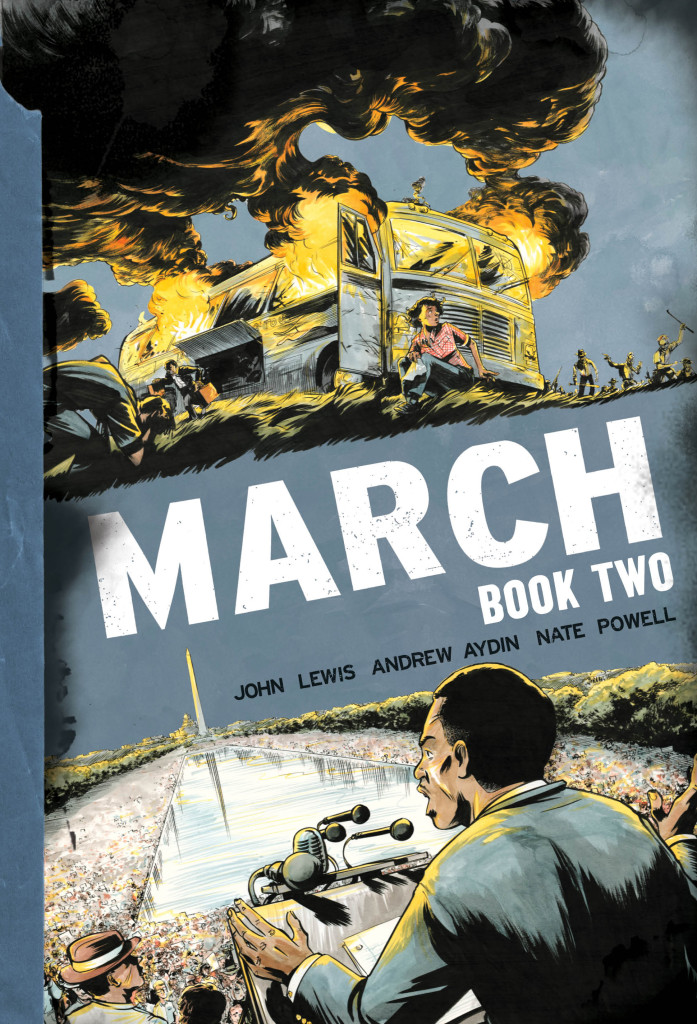

By 1960 Lewis had adopted a policy of non-violent protest at racial injustice, and his first jail sentence distanced him from his more conservative parents. He compensated by diving deeper into causes, his group targeting cinemas and fast food restaurants and politely requesting to be served. The response to peaceful protest induced escalating violence, the attacks sometimes led by officials, and at other times sanctioned by them. The Freedom Riders campaign became increasingly dangerous, with volunteers riding buses into states that had refused to desegregate them as demanded by legislation in 1960. Faith in a policy of non violence disavowing retaliation in the most extreme circumstances leads to tragedy for some.

It’s the story of the Freedom Riders that occupies the bulk of the book, and Lewis has unique insight into this landmark campaign, having volunteered early. He and co-writer Andrew Aydin convey the ease of casual bigotry being socially acceptable, and the disgust at state-sponsored assault. A victory was won, but at an awful cost, and it’s not just redneck racists revealed as crossing the line. Lewis further emphasises that someone who might be assumed to share the cause has feet of clay at a pivotal moment.

Lewis has the politician’s habit of distributing credit in public, which pleases those named and bores a nation. While his record stands against this being mere gladhanding, continuous passing mentions for people who’re not touched upon again clog the highway. Some names, however, resonate, and provide a conduit for the willing to investigate further. Try Stokely Carmichael as life well lived, for instance, if you’re not already familiar with the name.

As previously, Nate Powell’s artwork is excellent. The sketchiness endows an urgency to some events, and he emphasises others by using full pages lacking words. The horror of a firebombed bus is very effective, and he’s excellent on visual characterisation, while likenesses are an artistic weakness, although not one of particular relevance to this volume, where the truth of the content is the priority.

The final portion of the book deals with organising 1963’s March on Washington, the march itself and controversy over the speech Lewis planned to make, concluding with that speech. It still resonates today, and for comparison the text of the original version is printed in the back.

This portion of Lewis’ life has enough action, drama and tragedy to match any TV show. He also looks at the wider picture of the 1960s fight for equality, concentrating on the Alabama city of Birmingham, where he’d had personal experience of entrenched racism. His personal participation and current perspective enlightens regarding a tumultuous era when there was no certainty that the battle would result in victory. These events are contrasted with Lewis, already a senator, attending the Presidential inauguration of Barack Obama. That’s not subtle, but it’s earned. Lewis’ recollections conclude in Book Three.