Review by Frank Plowright

Frank Wedekind’s play Erdgeist (Earth Spirit) was completed in 1895, yet each new generation brings its own interpretation to what a rescued street child becomes. It’s been adapted as an opera, and most famously by German film director G.W. Pabst whose 1929 adaptation as Pandora’s Box was considerably ahead of its time and a restored version with English subtitles can be watched on YouTube.

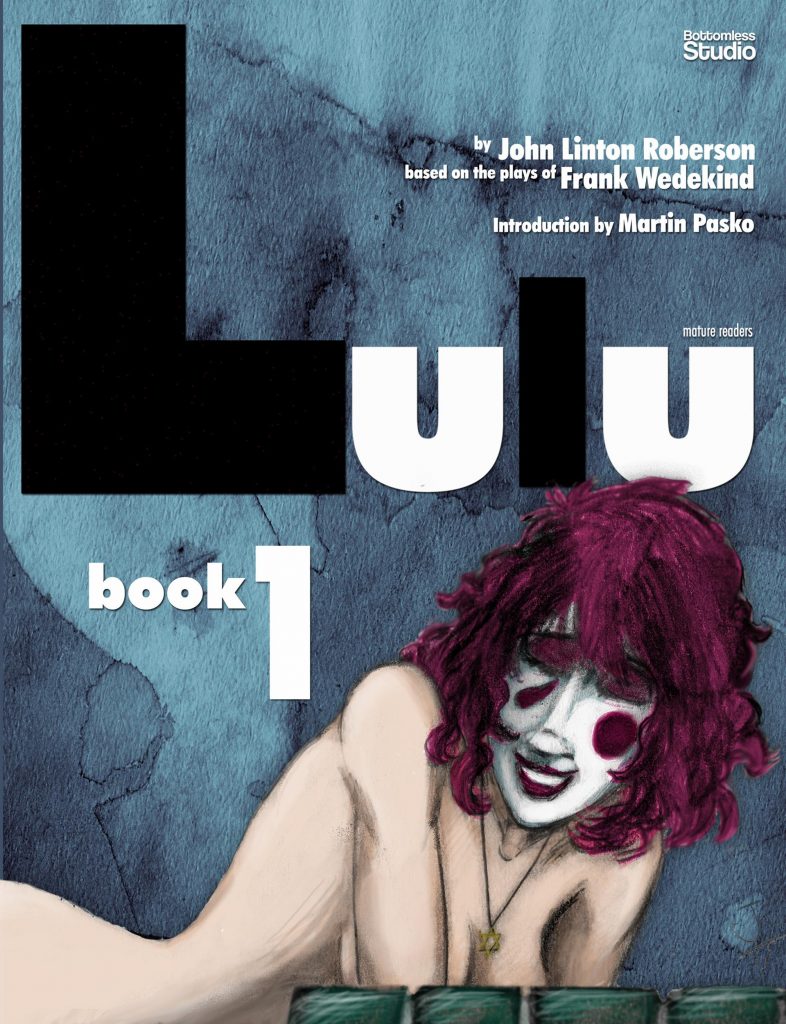

Lulu begins with artist Walter Schwarz talking with a visitor to his studio about the allure of the woman he’s been commissioned to paint. Her husband, one Doctor Goll, originally wanted her painted naked but for white pierrot make-up covering her face, but has changed his mind after the painting has been completed. The pair arrive at the studio for more posing, Goll advising that he calls his wife Nellie, whereas the other visitor, newspaper publisher Dr. Schoen named her Lulu, eventually how she refers to herself. Whether Lulu or Nellie, Mrs. Goll is very much a free spirit, uninhibited and revelling in her body, as does John Linton Roberson, bringing out the sexual nature so central to the play.

Roberson is faithful to Wedekind’s sardonic intent, but modernises the dialogue, and adds his own interpretations, often funny, one being Goll instructing Schwarz to add more paint as he’s paying for it. He also captures the sexual tension, with all three men in the first scene besotted with Lulu, as is Schoen’s son Alwa who subsequently turns up. There’s critical debate about whether Lulu’s character debases women by being objectified and having the sexual appetite of a fantasy figure, or whether she’s empowering for being entirely in control of her own sexuality and enjoying it to the full. Roberson definitively embraces the latter, joyfully illustrating her cavorting about Schwarz’s studio in her seduction of him.

The sample art is one of few pages when Lulu isn’t naked, yet Roberson still delivers her character visually in his appealing cartooning bringing to mind the underground comics of the 1960s and 1970s. As Martin Pasko’s introduction points out, there’s some skill in ensuring the cross-cutting conversations can take place without becoming boring for being restricted to the same location, while Lulu’s distracting presence further aids that.

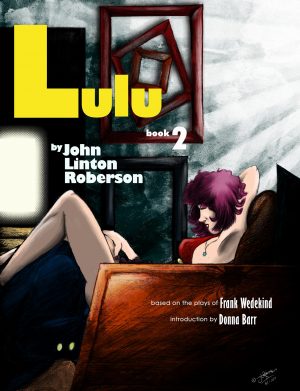

Wedekind was an iconoclastic individual and so is Roberson, and as Pasko also notes, Lulu won’t be to all tastes, not least because Book 1 only adapts the play’s first act. It would be eight years before a printed continuation appeared, and anyone who finds this original and refreshing won’t want to miss it.