Review by Jamie McNeil

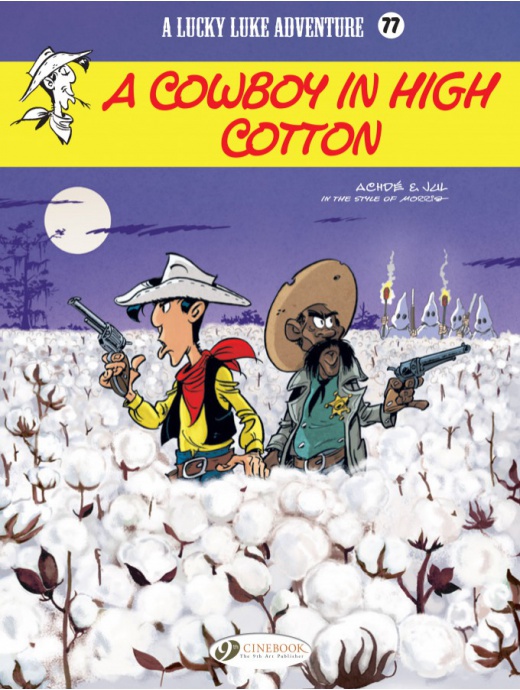

Lucky Luke is vacationing in a sleepy Kansas town when news arrives that he is the sole heir of one recently deceased Mrs Dolores Pinkwater, an avid fan of his numerous exploits. He is now the owner of the largest cotton plantation in Louisiana, but Luke isn’t thrilled about it. He intends to head down to Louisiana and hand it over to his employees. His friend Bass Reeves, the first Black US Marshal and a legend in his own right, warns him that things in the Southern states are not as straightforward as former slaves have reason to distrust a white man, even a well-intentioned one. Added to the mix are residual bitterness from the Civil War, white owners who don’t want the status quo altered, villainous neighbour Quincy “Q.Q” Quarterhouse, the Klu Klux Klan and the Dalton Boys.

While Lucky Luke the character can’t be described as racist, a man who treats all with courtesy, Lucky Luke the series is historically riddled with racist caricatures. Yes, Morris and his writing partner René Goscinny were from a time and generation where this was acceptable largely due to ignorance, but society has less excuse to be ignorant. However, racial stereotyping, as recently as 2018’s A Cowboy in Paris, has persisted with the excuse that it is respecting the integrity of Morris’s original vision.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter, Luke’s current creators Achdé (Hervé Darmenton) and Jul (Julien Berjeaut) have an opportunity to address that. The delightful The Promised Land, exploring Jewish influence on American culture, proved they are more than capable with sensitive subjects, but here the challenge is to prove that the Morris ‘style’ can provide positive depictions of race and ethnicity while distancing Lucky Luke from ignorant racism.

Achdé has been illustrating the series since Morris’ death and here produces what might be his best work. He captures the aristocratic opulence of the white land owners while displaying the desperate poverty and fear of their former slaves. The former are drawn in a very funny way, bringing out all their spiteful, spoilt, arrogant and selfish mean-spiritedness, purposely stereotyped for comedic effect compared to their swamp dwelling Cajun counterparts with their can-do charm and humour. Luke himself is genuinely shocked by the attitudes of his fellow whites, becoming angrier and angrier by the panel.

Drawing believable African Americans in the classic Lucky Luke style isn’t that hard if they’re drawn like normal people. Achdé does remarkably well with a rich array of characters infused with personality. The scenery is equally impressive, every panel a visual treat accentuated by Mel Acry’link’s colours, from the arid landscapes of the west to the muggy swamps of Louisiana. The problem is that the long tradition of drawing Black characters with big lips and vacant stares haunts Achdé’s efforts despite how brilliant his art is.

Jul’s sensitively handles America’s sordid racial history from the view of the oppressed, updating Wild West history in the process by introducing Bass Reeves. That alone is worth researching. The topic of oppression isn’t a pleasant one, but Jul lightens the mood with references to modern history and popular culture. In one panel a wide-eared boy called Barry announces he wants to be president one day. The responses to the revelation that Reeves is a U.S. Marshal are even funnier.

A Cowboy in High Cotton is a great rip-roaring tale and matches anything Morris and Goscinny produced in terms of quality. It doesn’t reverse the mistakes of the last 75 years but it is a step in the right direction.