Review by Ian Keogh

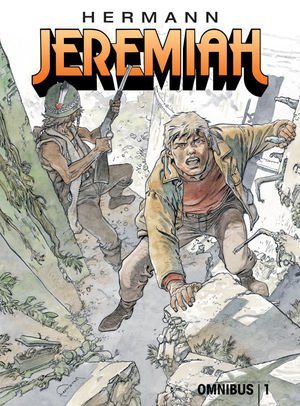

In a post-apocalyptic world Lone is a legend, the most fearsome fighter of all based on his war exploits, but that was a while back, and these days Lone prefers his own company. Hell, even getting to speak to him means travelling across heavily irradiated territory enough to kill anyone without a protective suit. He’s initially reluctant to help out a town infested with zombies, but there is a means of persuasion…

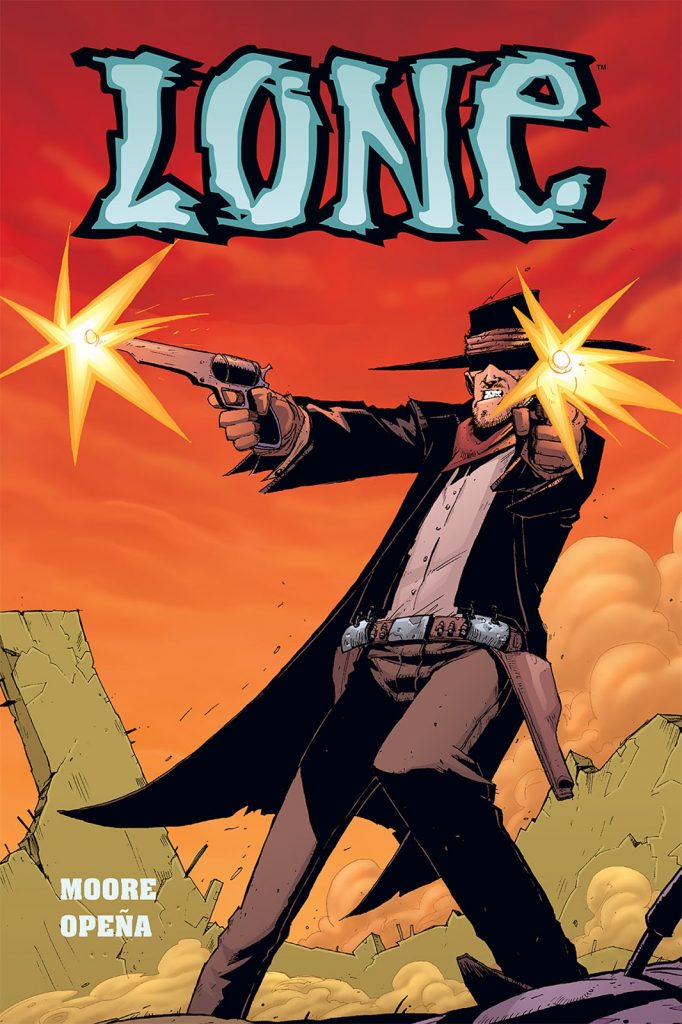

Lone may be drawn differently, but he’s manifestly Clint Eastwood, who it’s easy to imagine speaking every line of his dialogue. He’s introduced as seen through the eyes of brother and sister Mark and Luke, who like their biblical counterparts have slightly different views of the ways things are. It’s a pretty grim world, and eventually Stuart Moore explains how it came about, which ties into the problems manifesting now.

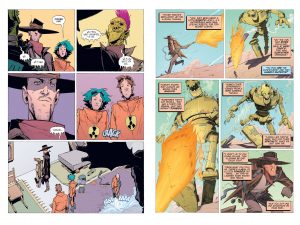

Jerome Opeña envisages this world in a spartan, stylised way. What he draws looks good, Jamie Hewlett’s Tank Girl seemingly an influence, but there’s not a lot of it, especially when compared with Albeto Ponticelli’s detail-rich back-up strip. Opeña, though, nails exactly what we want from Lone himself, his eyes almost never seen, hidden by the brim of his hat, and looking as tough as they come. Because this has all the Western trappings without being set in the past (see recommendations for others sharing that outlook), there’s a fair variety of novel threats for Lone to face, and Opeña’s clunky giant robot is a standout treat.

Moore provides an overall explanation for the anomalies, but it’s not comprehensive, and he chooses to leave Lone open-ended rather than reveal everything. That’s a mistake. Some dots can be joined, but too much is left unsaid. Likewise while Lone himself steals the show as intended, not all other cast members are as convincing. Luke’s proactive personality works well, though. Working against the story as a graphic novel is the original pacing supplying one threat per episode. Some are too prolonged, and while that pacing echoes the deliberately leisurely nature of Eastwood’s Westerns, it doesn’t engage as well episode by episode.

There’s no problem at all with the pacing of the two back-up strips. Ponticelli draws a railroad operator’s recollections of meeting Lone at the height of his legend. Moore throws in more anomalies, Lone is true to his personality, and the compact nature results in a more satisfying experience. The second is a prologue, introducing Lone and Cletus, who’s had a part to play in the main story. It’s slimmer, and not quite as satisfying.

Your reaction to Lone is likely to be dependent on how much you love a Western. There are so few published these days that any are welcomed by fans.