Review by Ian Keogh

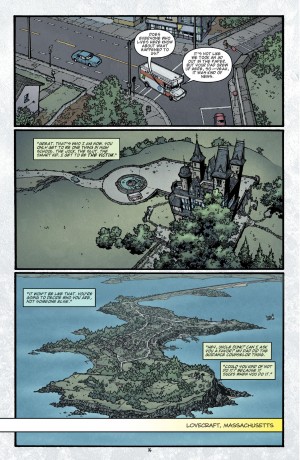

The Locke family move from California to the gothic old home known as the Keyhouse in Lovecraft, Massachusetts where father Rendell Locke grew up. Unfortunately the move is without Rendell as he was murdered in California, prompting the change of scenery.

Each of the three children has a different reaction to the horrific experience. In teenage Tyler’s case it’s guilt about the consequences of a conversation he never took seriously, and what he had to do on the day. A year or so younger, middle child Kinsey has become withdrawn, having sheltered the youngest of the family, Bode as mayhem occured within earshot. And no-one believes Bode about the Keyhouse, an ability to release his astral form and a presence in an old well among his discoveries. He seems to have adjusted best, but is having horrific nightmares.

Joe Hill’s plot is a well-paced horror drama perpetuating a sense of foreboding, and as we move deeper into matters his timing in switching scenes maximises the thrills. There’s a careful attention to detail applied to the way in which all three Locke children are characterised, Hill providing convincing little touches as each confides how the murder of their father affected them at the time and since. A two page sequence opening the third chapter has Kinsey’s first person narration disclosing that in effect her response has been to ensure she does nothing to draw attention to herself, and over a period of time she has modified her clothing to become as anonymous as possible. This in-depth personality construction extends further than the immediate family, and there are smart in passing references providing insight into people who aren’t spotlighted to any greater degree.

There may be an initial strangeness to the art of Gabriel Rodriguez, his cartooning stopping just shy of realism with its enlarged eyes and sometimes peculiar expressions, but a few pages into the book any sense of unease about this evaporates. Rodriguez is excellent at creating both a world and a claustrophobic atmosphere, knowing when to provide the long view in his panels and when to have it seem as if the panels are constricting the cast. He falls down a little when it comes to the depiction of violence, erring toward revelling in it rather than the true horror of suggestion, but some prefer the obvious. It’s a method that’s modified as the series continues.

Anyone who’s paid attention as the pages turn will have figured out the maguffin that becomes prominent toward the latter stages of the book, but that’s not the point. Knowing something and knowing its purpose are entirely separate, and while the purpose is revealed, the consequences aren’t. What is apparent is that Hill has a far bigger picture in mind, and the manner in which he’s established his series premise in this book has an admirable simplicity about it. Enjoy your horror fiction? You’ll rave about Welcome to Lovercraft.

The series continues with Head Games. Both are combined in the first Master Edition, or the complete series is gathered as a slipcased set, or as the oversized hardback Keyhouse Compendium.