Review by Frank Plowright

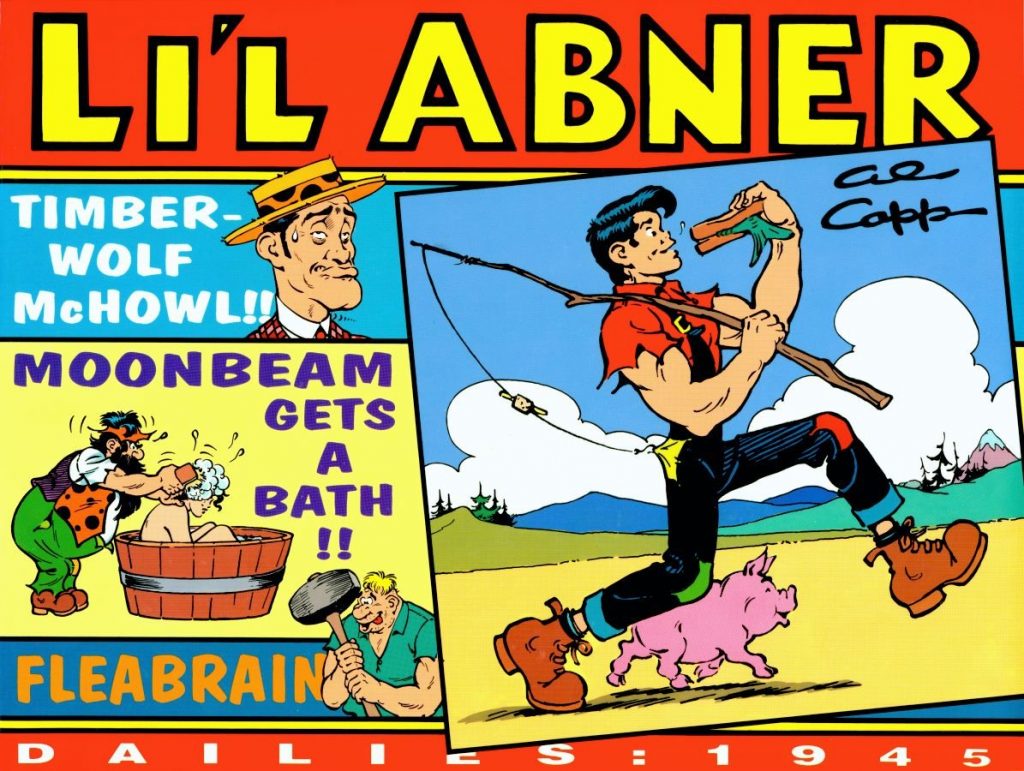

Although titled Dailies 1945 for convenience, for the sake of a smooth read this collection picks up the strips where Dailies 1944 finished in early December, and runs through to mid-November 1945, leaving the remainder of the year for Dailies 1946.

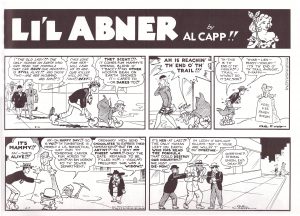

That’s almost irrelevant. Al Capp has now hit his groove, and packs so much quality entertainment into the daily strips it makes this selection a compelling read from start to finish. An example of Capp’s brilliantly conceptual mind is a villain named Mr Armstrong, able to commit any crime and get away with it on the basis he has two sets of arms and hands. Were he to be fingerprinted, he’d just use his other hands. The Capp of the 1930s would take this idea and run with the mystery for weeks, but the more experienced creator recognises the limitations and uses him as a throwaway, in and out of the strip in five days, his purpose served. The final strip of 1944 has Abner sneaking into Capp’s office and emerging distraught on reading the plans for him over the following year, an inventive breaking of the fourth wall.

Broadly, many plots are those used in the strip before: Mammy Yokum goes missing; Abner may be tricked into marriage; a seductive radio voice causes swooning; and the annual Sadie Hawkins Day chase. The difference, though, is the astonishing speed with which Capp zips through them, rarely more than two weeks continuity used before moving onto the next plot, and often including diversions along the way. Consistent surreal touches are applied, not least regarding the reasons people have for wanting to kill Abner. One such sequence has foreign visitors with a rule that anyone who touches the skin of their leader must die, and in avoiding this over a prolonged chase Capp throws in a brief clinch with a taxi driver, a tobacco promotion and the introduction of the dim Flea-Brain in a factory scene.

Li’l Abner has now moved beyond the humour being dated and diminished by being recycled in the decades since, and the sheer pace of events means any brief sequence that has dated is followed by something that still dazzles. The audacious ways in which Capp finagles his way out of tight plot corners is to be greatly admired, there are returns for eccentric oddbodies like Big Barnsmell, Available Jones and Moonbeam McSwine, and Capp is ever more visually inventive. A sequence down a drain where somebody is trying to kill Abner (another misunderstanding), has the viewpoint twisting every which way.

Occasionally Capp runs a joke into the ground, such as mogul Westbrook P. Buckingham’s peculiar hatred of feathers, including a sequence featuring native Americans that’s now of its time and reinforcing inaccurate stereotypes. Generally, though, he’s a fair judge of what works and what doesn’t, and while the increasingly satirical tone of Li’l Abner in 1945 falls a little below 1944, these strips will still hit the funny bone.