Review by Frank Plowright

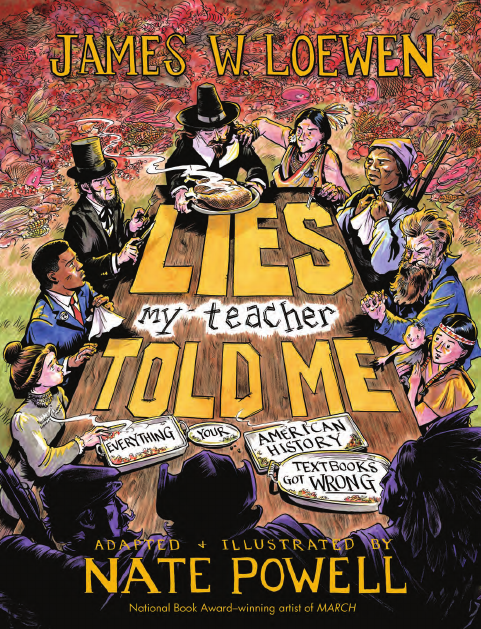

In 1995 James W. Loewen examined school history textbooks and discovered a very narrow interpretation of events, rarely illuminating them in the context of the present, and at worst glossing over atrocities to present myth building in the name of nationalism and patriotism. It’s strange, then, that he should run with a sensational title misrepresenting the content. It’s the textbooks at fault, not teachers locked to a curriculum.

Nate Powell’s visual interpretation is not so much graphic novel as illustrated book, since large blocks of factual text accompany pertinent pictures as per the sample art concerning President Woodrow Wilson’s frequent interventions outside US borders. Some were invasions by any standards, yet whitewashed and excused in the books history students learn from, most also ignoring Wilson’s overt racism. Powell’s adapting what is after all an academic work by a sociologist despite the historical research, and is very faithful, emphasising details via maps, diagrams, portraits or evocative representation of events. An occasional cartoon joke signifies Powell’s own personality.

From an opening dealing with Wilson and Helen Keller, Loewen moves on to deal with significant sins of omission, selective and biased interpretation and the downplaying of anything other than a white version of history. A former student wondering why they’d never thought who Americans were before Christopher Columbus and how his arrival changed their lives is almost a call to arms, as Loewen proceeds to explain how history books are written for the descendents of those invading Europeans. Quoting liberally from studied textbooks, he begins with Columbus, about whom very little is actually known. History books present speculation as fact, and ignore his pretty well inventing the transatlantic slave trade, despite his never referring to it by that name.

From there the spotlight falls on slavery, the Civil War, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War and other topics. Loewen highlights a depressing multitude of instances where the propaganda of the past has become accepted history, with belief in religion justifying pretty well any act of theft from ‘uncivilised’ people. Just a minor selection of reality not emphasised in the textbooks studied by Loewen is that a third of the USA has been Spanish for far longer than it’s been American; the wrong tribe were paid to purchase Manhattan; the first non-native settlers of the USA weren’t the Pilgrims, but escaped black slaves who overthrew their Spanish overlords a century earlier; and “national interests” so frequently means the interests of corporations. Loewen astutely notes that when other nations do something similar it’s labelled “State sponsored terrorism”.

The righteous sense of injustice of a nation preaching democracy while supporting tyrants is well transferred by Powell, while Loewen distils some remarkable evidence, such as the portrayal of slavery abolitionist John Brown in textbooks over the decades as a marker of the period’s level of racism. Regarding more recent events Lowen’s conclusion is that American history textbooks appear to take the American government trying to do what’s right as an absolute, so avoid mentioning mistakes and atrocities.

There’s no disguising what a depressing catalogue is presented to anyone sincerely believing truth should prevail. In the final chapter Loewen discusses who benefits from such a shoddy approach to teaching children history, and notes that lies, myths and inaccuracies are perpetuated because so few people read a history book after leaving school. However, he also presents ways in which the teaching of history could be improved. Powell takes a landmark book (and its updates) and presents a version maintaining the integrity while making it more accessible. It’s important and it’s magnificent.