Review by Frank Plowright

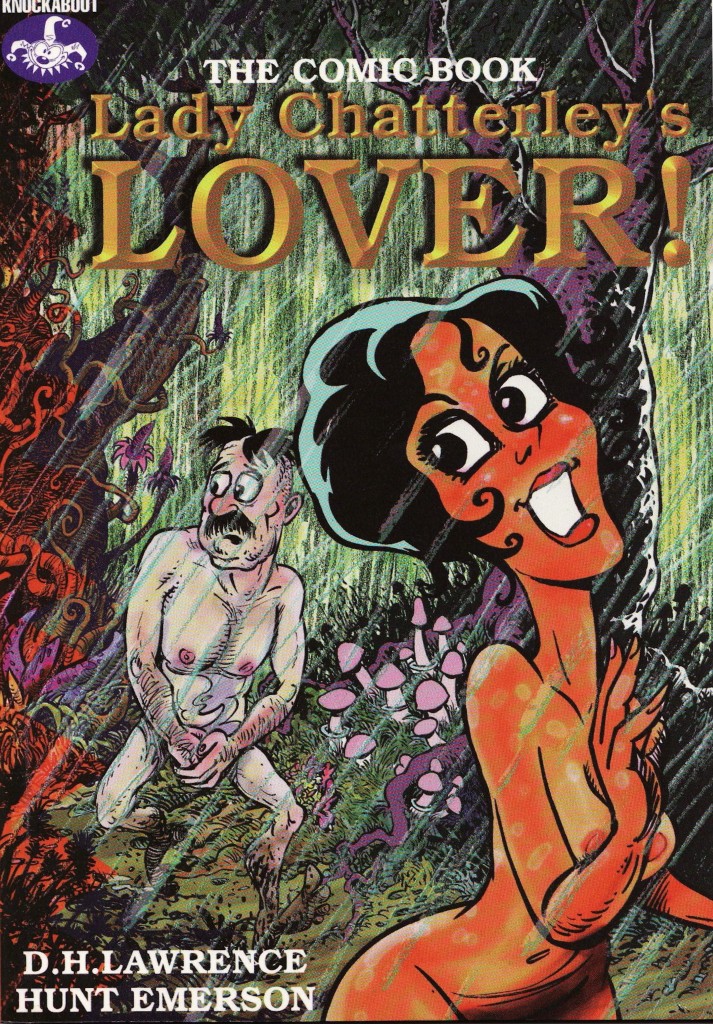

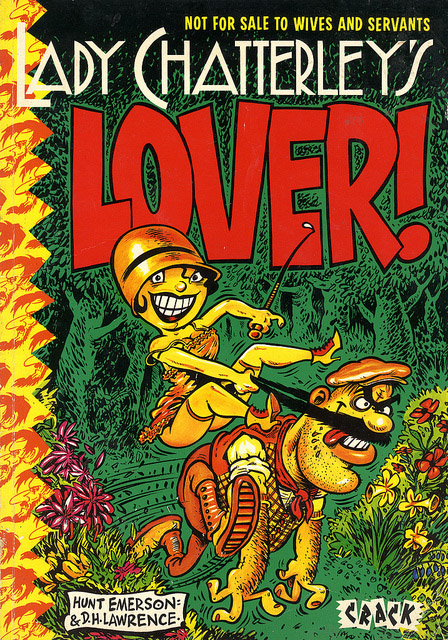

Hunt Emerson is Britain’s greatest living comics cartoonist. To paraphrase Sgt Bilko, were he French they’d erect a statue of him, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover best exemplifies his inordinate talent.

For all its notoriety, in the UK the original novel’s salacious reputation rests more on its ground breaking status as the successful subject of a court case that challenged Britain’s then repressive culture of censorship. Despite the fame, and honesty about sex, Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a very dry read today. It’s a very odd or sheltered person who’ll now experience an erotic twinge from reading the famous shrubbery draping scene, and even the earlier simmering undercurrent of repressed desire is matter of fact.

It wasn’t chance that Emerson alighted on Lady Chatterley’s Lover for adaptation, but a deliberate evocation. For a period from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s his publisher Knockabout endured a series of police raids on spurious charges of distributing obscene material, resulting in time-wasting prosecutions. They were cleared on every occasion, but the time taken to defend court cases, and the costs took their toll, not least in stunting the company for a decade.

The story begins with the marriage of the landed Clifford Chatterley to the young Constance just prior to World War I. He returns from that conflict a broken man, wheelchair bound, and lacking the desire or capacity to fulfil marital duties. An heir being of paramount importance, he suggests to Constance that she finds solace elsewhere, and notes he’s confident she’ll select the right sort. The right sort by his definition, though, is far from Constance’s desires.

As introduced by Emerson the groundsman Mellors is a rough and ready unreconstituted brute, yet simultaneously seen through Constance’s eyes as dashing and noble. It’s a wonderful method of adaptation. Emerson accentuates the comic throughout, which is his style after all, but is also capable of delivering the tender and heartfelt when required. Constance’s tears over a baby chick is one such moment, yet accompanied by Emerson’s illustration of a goofy, goggle-eyed chick.

His artwork is wonderful from first to last, capturing the era despite the satire, but pitching his exaggeration perfectly. At one point he illustrates the garden at night as if by Dr Seuss. Other artistic highlights are a collage spread abbreviating Constance’s tour of Europe, preceded by a wonderfully stretched cruise ship, and some hilariously hyperbolic scenes of unbridled lechery and orgasmic consummation.

Previously known for his more eccentric and whimsical material, Lady Chatterley’s Lover provided a career sideline for Emerson. He’d progress to adaptations of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Casanova’s memoirs and Dante’s Inferno, yet while all good, none possess the impassioned spirit he brought to this work.