Review by Will Morgan

Approximately twenty years into the future of the DC Universe, the world is a much bleaker place. Superman has turned his back on the human race to live in seclusion, and most of his generation of heroes followed his example and retired. But the new generation of ‘heroes’ is an ever-increasing threat to the survival of the world.

Meanwhile, an elderly minister, Norman McCay, is visited by the Spectre, the latter having forsaken most of his humanoid mannerisms and now appearing only as a vessel of judgement upon the world. He needs a human anchor who seeks justice. McCay, a former friend of the late superhero Sandman, Wesley Dodds, was bequeathed some of Dodds’ own insight, and together he and the Spectre survey what the world has become, and the demigods who will bring it to its close.

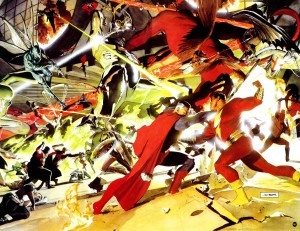

Largely deprived of opposition, the younger ‘heroes’ spend their days in violent conflict with each other, heedless of civilian harm. One such incident causes a nuclear accident that wipes out the state of Kansas, so Wonder Woman forces Superman to emerge from retirement and lead the older heroes against their rebellious offspring. But this is not a simple inter-generational conflict; Wonder Woman has her agenda in provoking Superman from seclusion, and Batman is caught in the crossfire, establishing his own anti-authoritarian movement.

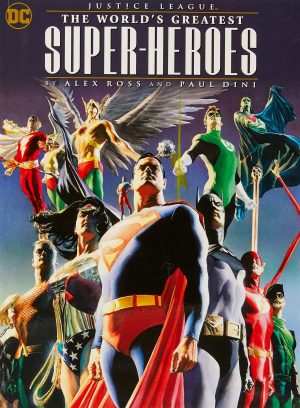

Alex Ross and Mark Waid’s story is complex and intriguing, though sharing many sparking points with Mark Gruenwald’s earlier, and under-rated, Squadron Supreme. The reader is left guessing about full motivations for just long enough, the characterisation of the lead triumvirate is strong, and there are endless fascinating bits of side business and subplots – often expressed wordlessly in the background of panels – achieving a suitably multi-layered feeling. More importantly, one feels genuine shock at the scope of the final conflict, and the ending doesn’t seem anticlimactic, which is too often the case with these self-conscious ‘blockbusters’.

There are nits that could be picked; the revelation of one of the main villains, a darkened recasting, is disconcerting, even though plausibly explained. And Alex Ross’ lush and majestic painted artwork, while a treat to the senses in battle scenes or imaginative vistas, is less effective in conveying subtleties of emotion. McCay and Clark Kent/Superman are superb, but he tends to fall too readily into stock poses on Batman, and the female characters suffer particularly, presenting the defaults of ‘angry’, ‘smiling’, or ‘vacant stare’. When Wonder Woman is such a major force in the narrative, this deficit is keenly felt.

Nevertheless, the overall result is stunning to the eye and satisfying to the mind. Kingdom Come knows its limitations; it doesn’t aspire to be Watchmen. It’s mainstream superheroics, and proud of it, but it’s probably one of the finest examples of mainstream superheroics ever.

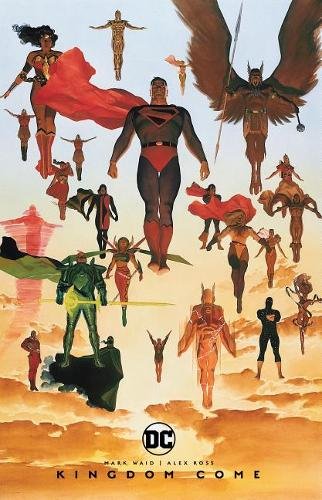

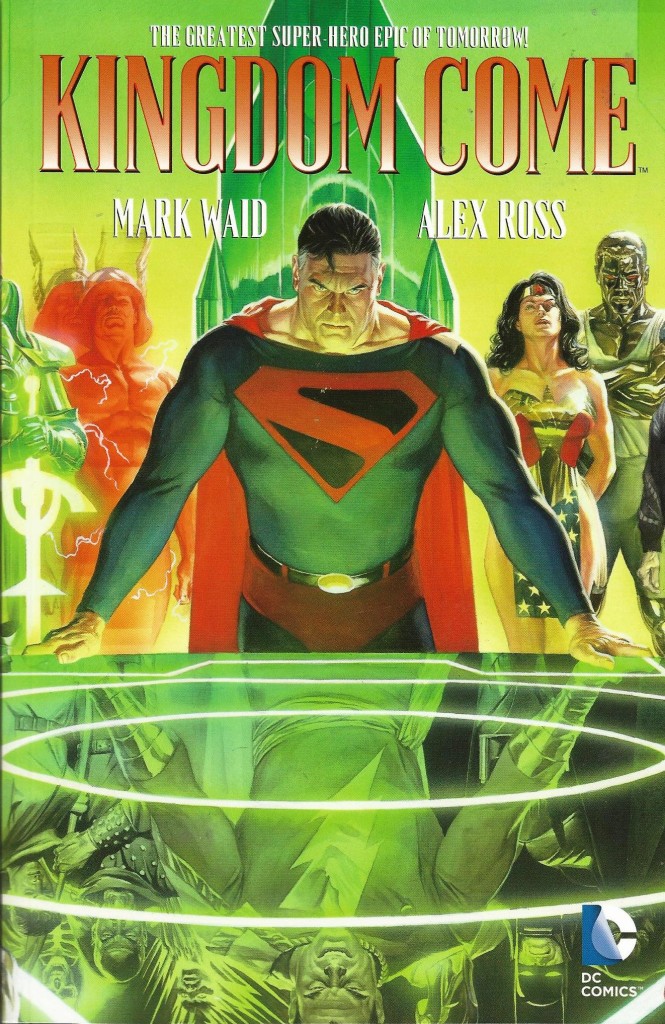

The paperback edition features Ross’ character sketches for six major players in the series, a foreword by Elliott S. Maggin, a “Who’s Who” key to the participants on each of the original series’ covers, and a selection of promotional artworks. There’s also the development of an interlude with Orion of the New Gods, not featured in the original comics.

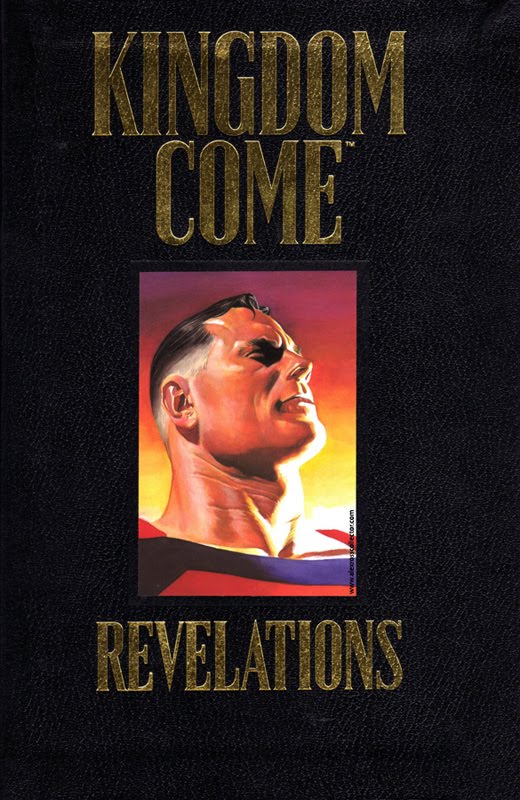

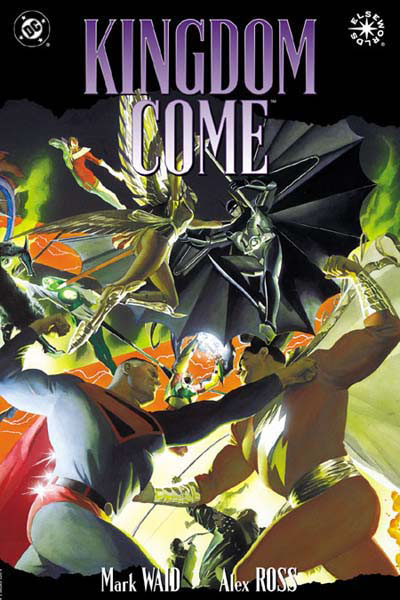

The 1997 limited hardcover edition is two slipcased volumes. The first primarily presents the story itself, with the bonus features from the paperback releases shunted over to a second book, Revelations. This is a mammoth mound of bonuses, including character designs, with accompanying commentary, for more than 100 other characters, a detailed fold-out genealogy for the cast, character annotations, credits for the primary models Ross used in creating his interpretations of the characters, and Waid’s preface.