Review by Frank Plowright

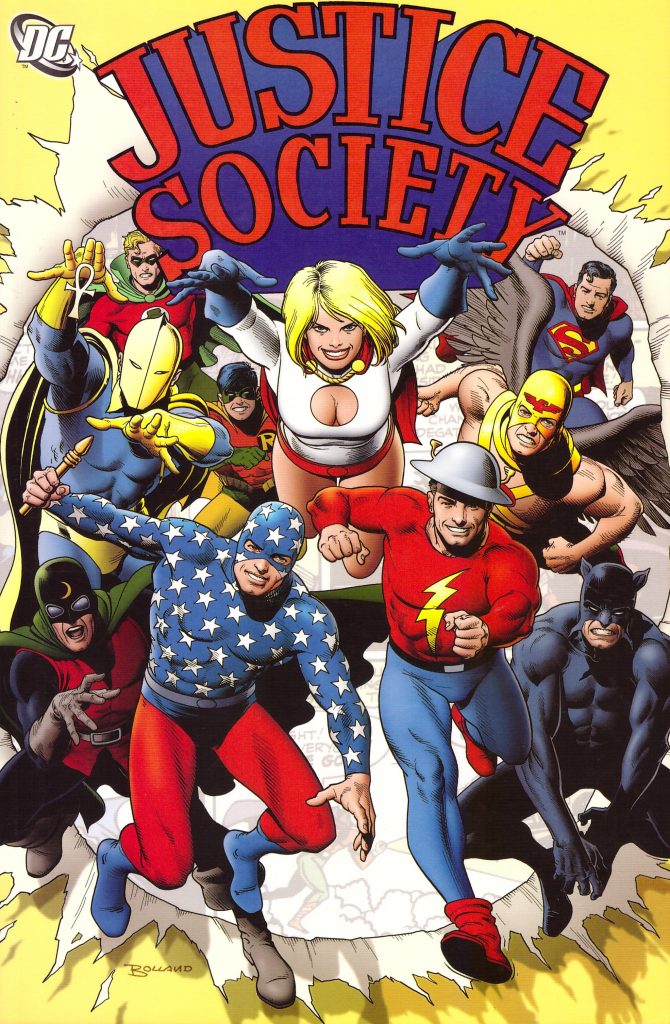

The Justice Society of America was the first superhero team, fondly remembered by comic fans of the 1960s who’d been kids during the 1940s, while annual guest-star slots in Justice League were well received. What fans really wanted, though, was the Justice Society restored to their own title, which finally happened in 1976. This is the first of two volumes reprinting the results, and the peculiar expressions on Brian Bolland’s cover characters, midway between grin and grimace, may well be his editorial comment.

DC wisely dispensed with the 1940s format of All-Star Comics, in which Justice Society members only gathered together at the start and finish of long stories, but separated for individual adventures in between. Youth was also introduced so the JSA appealled beyond nostalgic fans in their mid thirties and up. The Justice Society’s adventures occurred on Earth 2, where Robin was an older teenager in leggings, not shorts, but he disappears after the first story. Another 1940s revival, the Star-Spangled Kid is prominent on the cover, looking dated, which was already the case in 1976. The third introduction has stood the test of time. A story circulates that inker Wally Wood would increase the size of Power Girl’s breasts with every issue, but she’s introduced as phenomenally endowed, and so she remained, although after five issues her cut-out costume was filled in.

The ‘kids’ save the day after a Justice Society actually shown voting on a proposal to investigate disasters around the globe have failed. Gerry Conway’s two part opening plot also includes heroes explaining themselves, the ranting villainy of old JSA foe Brainwave, and situations ridiculous even for superheroes. As a much desired and long awaited revival, it’s terrible, with Ric Estrada’s art looking as if he’s posed a few action men in superhero costumes. Why anyone bought further issues is a mystery worth investigating.

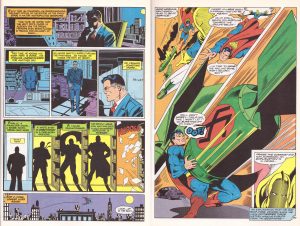

However, things improve. DC wipe credits from the reprinted issues without providing them in introductory pages (belatedly included in the following volume), but Keith Giffen’s layouts for Wood (sample left) is a very appealing combination. Giffen breaks down Conway’s plots into small panels, frequently ten to a page, and it makes Conway’s earlier stories look more interesting than they actually are. By his third two-parter, featuring a revived Lemurian God, Conway has settled into a more comfortable pattern, moving toward Marvel’s 1970s style of superhero comics, with subplots and foreshadowing. Accept the storytelling quirks of the time and the constant artificial clashes of young and old and male and female, and there’s still fun to be had, although the thrill of returning villains barely seen since the 1940s is lost as they’ve been used ever since.

The final third of the collection is the work of the team responsible for all of volume two, Paul Levitz arriving as writer an issue after Joe Staton as artist. Both take time to settle, but the final story, the previously unrevealed World War II origin of the Justice Society, still reads well, and was completed several months after their first work here. Staton’s sense of page design has come on in leaps and bounds, instead of looking cramped his panels have space to them, and there are a couple of wonderful Superman pin-ups.

For all the appetite for a Justice Society feature in the 1970s, the initial work is a textbook example of being careful what you wish for, lacking basic energy, never mind style or inspiration, but issue by issue it improved into something readable, with the best to follow in volume two. The hardcover collection All Star Comics: Only Legends Live Forever combines both.