Review by Frank Plowright

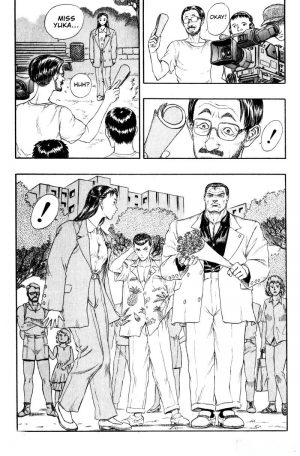

Even by Japanese standards, Japan is a completely mad graphic novel, and one that feeds back into centuries old ideas of isolationism. It’s a parable suggesting the idea that by 1992 Japan had become too economically powerful, resulting in jealousy from other countries around the world, emphasised in the early pages via a very strained comparison with ancient Carthage, eventually destroyed by Rome’s military might. Via some mystical mumbo jumbo a group of seven Japanese are transported to a future where Japan has been wiped out, partly due to envy of their economic stability, and partly because of ecological conditions, the only survivors of the nation scattered around the world. Fortunately among the time displaced is a massive and brutal Yakuza gangster, Katsuji Yashima, a lovesick puppy around the reporter who featured him in a documentary.

The more the book continues, the more nationalistic it becomes. Japanese citizens now live in shanty towns in Neuropa, much prized as slave labour because they’re such hard workers, but Yashima knows why they’re meek and downtrodden, it’s because they’ve lost their pride. And as for the Japanese youngsters who play bit parts, their primary purpose is to be on the end of Yashima’s lectures about how they expect everything to be handed to them on a plate. The irony of this being spouted by a gangster isn’t addressed. The women in the party have a further purpose, desirable for sexual exploitation, this by another group of Japanese refugees who’ve banded together to fight back. Not that it earns them any approval from Yashima. They’re just pirates as far as he’s concerned. Again, the irony isn’t addressed. Hell, if there’s one thing that makes Yashima madder than a lack of national pride it’s someone abducting his girl.

It’s difficult to know whether Japan is to be taken at face value or intended as exaggerated satire of a certain type of nationalist, but all online indications are that it’s serious, which is problematical as that moves it beyond daft to offensive. Buronson’s underlying messages are that might is right, that national pride is paramount, women are ornaments to be fought over, and they’ll drop naked into a man’s arms if he wins a fight. It might have been written in 1892 instead of 1992.

Kentaro Miura draws this dystopian Mad Max style world adequately enough, and some occasions when Yashima Hulks out are very funny, but otherwise there’s nothing memorable beyond the designs of the motor vehicles.

Everyone’s entitled to their opinion, but this lacks respect for anything other than a very narrow worldview, and even putting that to one side, Japan’s plot doesn’t stand up to an iota of logical scrutiny.