Review by Frank Plowright

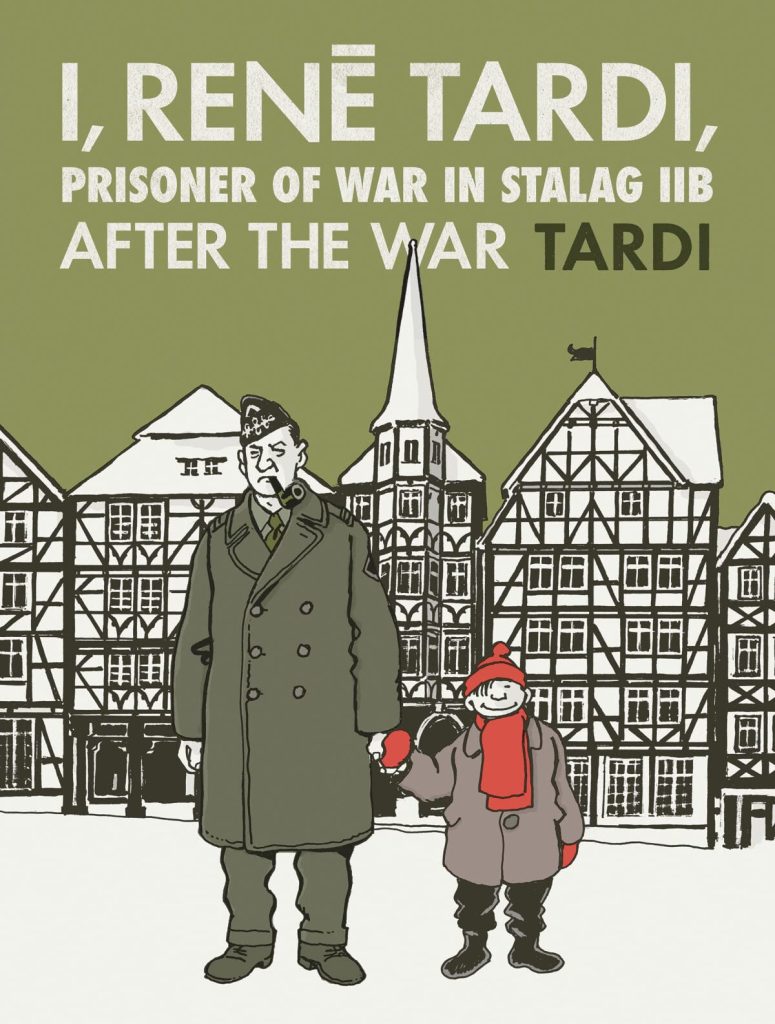

Jacques Tardi’s detailing of his father’s World War II experiences concludes with René Tardi returned home to France after the war, having lived through four gruelling years of captivity followed by an appalling forced march.

After the War has less concentration on René’s experiences, continuing a process begun toward the end of My Return Home, and he’s gradually phased out as Jacques reminisces about his youth of the later 1940s and the 1950s. René’s thoughts when mentioned are scattershot and broad ranging. He holds forth on what happened elsewhere during his years in the stalag, and on the aftermath of World War II, with the young Jacques running though historical events not mentioned. René is considerably bitter, let down by his country, not shy of calling out the French who profited from war and the ongoing process of brushing less heroic aspects under the carpet. Much may surprise, with the sheer number of rapes committed by ‘rescuers’ astonishing.

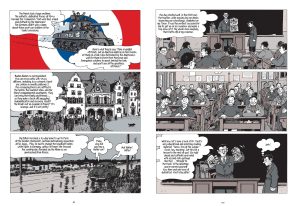

If the narrative drive is more fragmented, the post war period permits Tardi to draw some beautiful postcard scenes in his precise way, showing lovely areas not devastated by war. Among them is Bad Ems on the Rhine, where he lived as a child because René kept signing up for more periods of army service, some of which occurred in Germany. The art remains strictly three widescreen cinematic panels to the page, but now with more items highlighted in colour, increased when Tardi recalls the comics of his youth. The panels are packed with his incredibly expressive people such as the gloriously drawn class of boys on the sample art.

There is a presumption on the part of the creative Tardi that readers will have kept up with family relationships and footnotes from the earlier volumes. Anyone who hasn’t may find it confusing at the start when the narrative moves without any lead-in to other characters. Early on the recollections briefly switch from René to the memories of Dominique Grange about her father returning home after war service.

As After the War continues it adheres to the title, but moves further and further away from Tardi senior as Jacques recalls the pleasures and inconveniences of his childhood, and what would now be considered neglect. These will have been if not universal, then certainly commonplace, but the elapsed time since provides eccentric glimpses into a bygone era, and represents the attitudes of ordinary people to their circumstances. Items of considerable impact are supplied in passing, such as the American decision to finance the rebuilding of West Germany to provide a barrier to Soviet expansion, while France, nominally among the war’s victors, remained backward.

Tardi is a natural storyteller and a phenomenally gifted artist, but the more anecdotal nature and less shocking events of After the War renders it an interesting read, not a compelling one.