Review by Ian Keogh

Starting in 2005 Drawn & Quartely published three carefully curated anthologies presenting the groundbreaking work of Yoshihiro Tatsumi along with interviews and informed introductions. Is there any purpose, then, in looking out this first English language presentation of Tatsumi’s work from 1988? Particularly when Tatsumi noted he knew nothing about the book until it was published. The answer is a cautious yes.

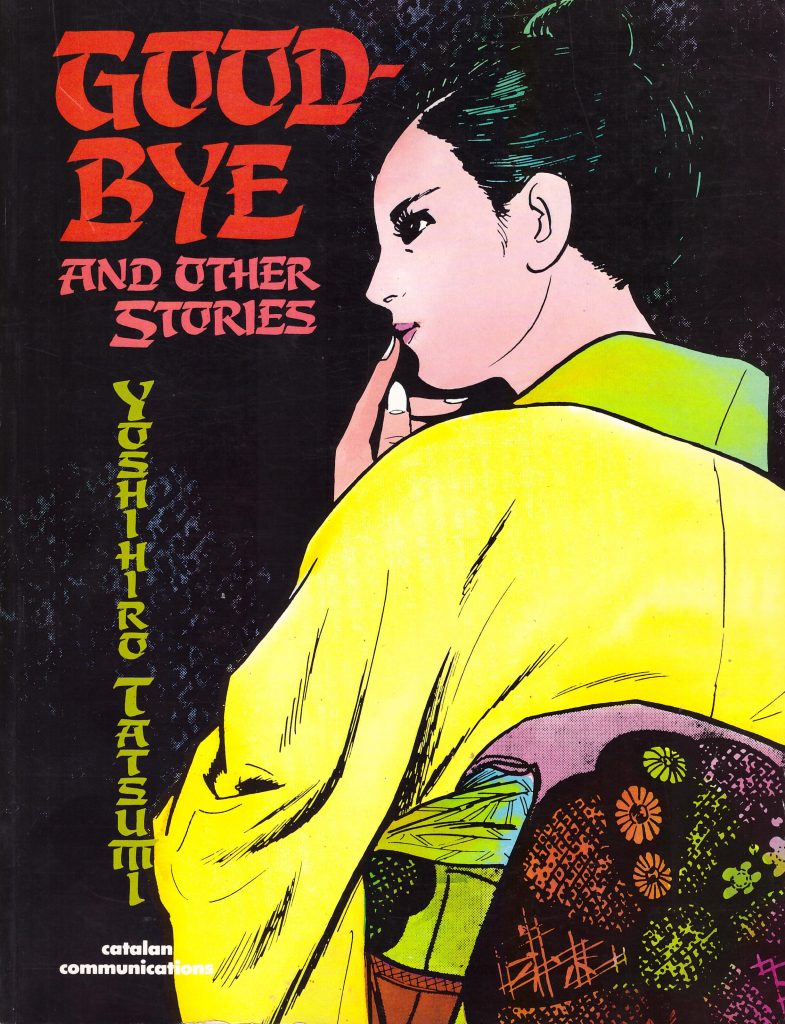

Most importantly this edition contains three stories not included in the more recent publications, and they’re all good, if accounting for just sixteen of 103 story pages. Also worth taking into consideration is that the art is presented at a size roughly equivalent to that Tatsumi drew for in Japan. On the downside, a chemical process involving either the cover card stock or the colour inks used on it has resulted in the first and last pages browning considerably. It’s not so important for the title page, but the final story page is the epilogue to ‘Unwanted’ one of the three stories missing from the Drawn & Quarterly collections.

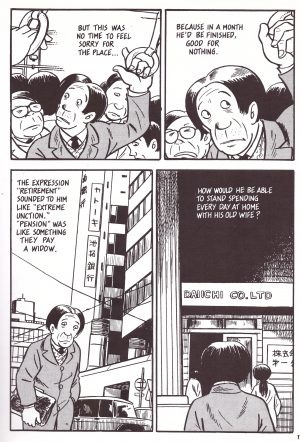

These stories were produced between 1969 and 1972, and at a time when Japanese comics increasingly looked toward the fantastic, Tatsumi based his stories on observations of the ordinary people he saw in the streets every day. From the late 1960s he concocted sordid dramas about unfulfilled ambition, confinement, fear and anger as Japan experienced a state of flux, transitioning between its imperial past and technological future. It’s uncompromising work, bleak and brief character based crime stories without happy endings. The attention-grabbing cover is taken from the longest story not included in the Drawn & Quarterly collections, about a woman who returns home two years after she left, a decision taken almost at whim, although prompted by underlying discontent. It’s a masterpiece of repressed anger, and squirmingly awkward, a sort of compact Abigail’s Party about fundamentally incompatible people.

Tatsumi doesn’t flinch from the unsavoury, in fact, he positively wallows in it, with the title story exemplifying his matter of fact spotlight, and possibly being his metaphor for Japan’s decline. With Japan in disarray immediately after World War II, the means of making money are very limited for young women without husbands, and while Maria has taken control of her life, it’s by prostitution. Her dissolute father, a returned soldier has also been cut adrift, and Maria takes drastic and almost unthinkable action to rid herself of this disappointment in her life. Tatsumi’s women are superficially compromised, but almost every single one of them has forged their own path, while many of his male characters are swept along by circumstance, victims of their own poor instincts.

These stories have become timeless, and almost every single one of them retains its power to shock, which is some achievement considering how far attitudes have progressed. It doesn’t appear as if much more of Tatsumi’s work will be translated any time soon, so every page is precious.