Review by Karl Verhoven

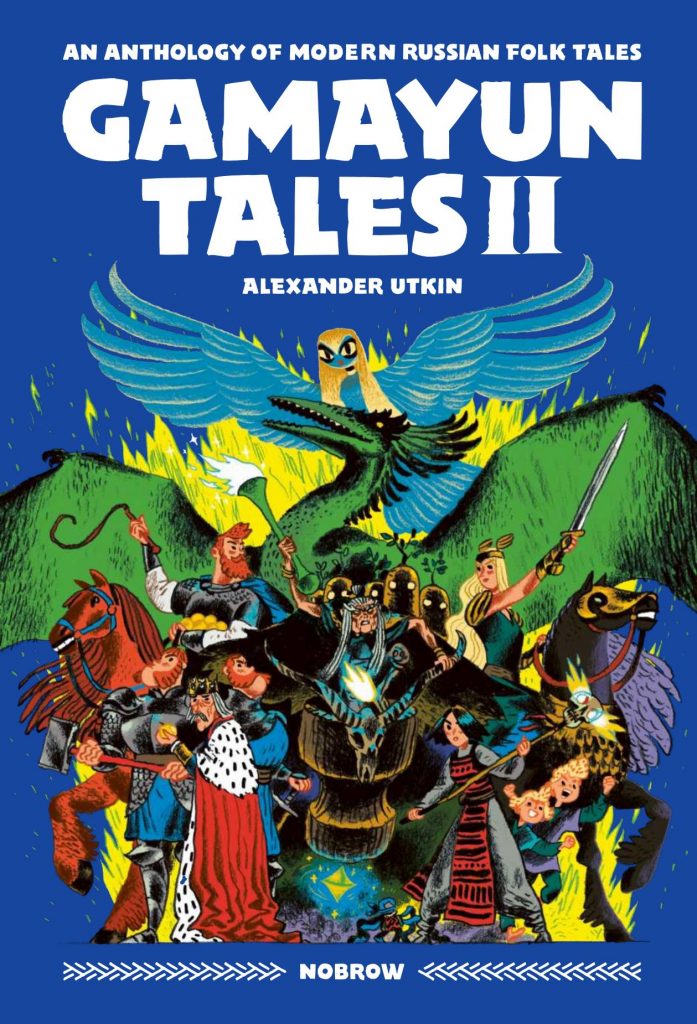

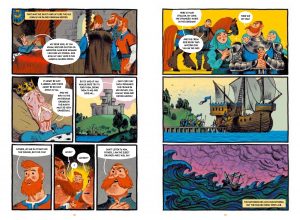

Given that fairy tales and myths originated separately around the world in different cultures, should it be surprising that common concerns feature? These are exemplified in ‘Vasilisa and the Doll’, where an unfortunate girl is set three tasks to acquire a prize, and it begins with tragedy, depriving eight year old Vasilisa of a loving mother. She passes on a doll on her deathbed, saying it will help her daughter in times of need, which are not long in coming as Vasilisa rapidly ends up with a wicked stepmother and watches her father wasting away. She’s a teenager by the time her father’s only hope seems to rest on Vasilisa convincing fearsome witch Baba-Yaga to provide a cure. Baba-Yaga is a gift to any artist, an old crone who lives in a house prowling the landscape on chicken legs, while she flies around in a giant pestle and mortar adorned with a horned skull. As seen on the sample art, Alexander Utkin doesn’t disappoint.

In the first Gamayun Tales Utkin frustrated by having his narrator, the bird with a human head Gamayun, casually toss out “but that’s a story for another time”. It happens again, and proves equally frustrating, although given the way we leave Vasilisa there’s relative confidence that she’s capable of coping with whatever’s thrown at her. It’s been a surprising and entertaining journey.

Providing some closure here are the two chapters of ‘The Golden Apples’, which were mentioned in passing last time. “Take a bite of an apple and it will bring relief from sickness or injury”, explains Gamayun, continuing “eat the whole apple and any illness will be cured and you’ll feel young and strong again”. It makes you wonder if it were golden apples Baba Yaga was chewing away on earlier. We’re introduced to an ailing King and his three sons, and there’s a fairy tale feel as it’s apparent the sons have different characters and one after the other heads north in search of the magic apples that could cure their father. The result is a fantastic twisting adventure, virtue playing off grasping desire, and unpredictable to the end.

Utkin’s pastel painted art is just as expansive and joyful as it was last time round, although this time not quite as bright. These are more gruesome stories than those told in the first volume, and Utkin ensures the full horror is left to the description rather than shown.

With some reservations about the number of times Gamayun cuts off a story saying it’s a tale for another time, this is a selection of stories every bit as captivating as before. They ought to dazzle and delight children and adults alike.