Review by Frank Plowright

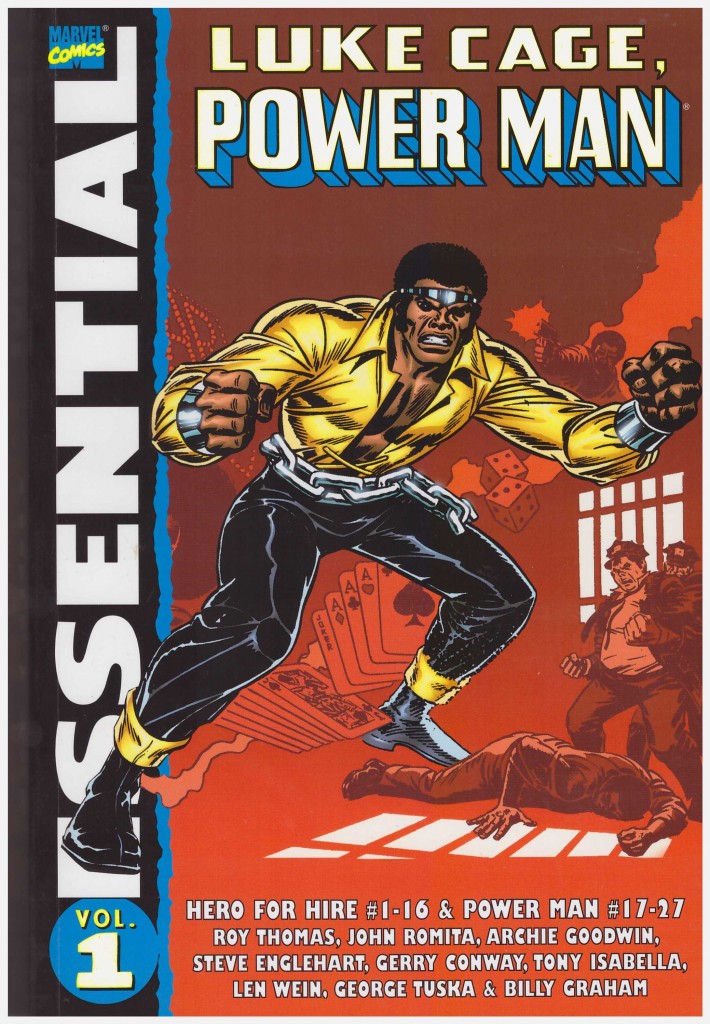

When Luke Cage was launched in 1972 it was big deal for Marvel. His was among several titles that year intended to broaden their regular focus (Warlock, Tomb of Dracula, Shanna the She Devil, Red Wolf), and more importantly he was a statement as the first African-American hero in his own title. Never mind that it was created by a bunch of white guys, the intentions were good even if it took Billy Graham a year to progress from inking George Tuska to full time penciller.

This bumper package gathers just over the first two years of Luke Cage’s existence. Unfortunately, for all the good intentions, there’s a sprightly start, but the quality dips rapidly.

Series creator Archie Goodwin pulls his inspiration from the era’s blaxploitation culture, cheaply made movies featuring jive-talking, street tough hustlers intended for a specific demographic. Genuinely framed for a crime he didn’t commit (although he did commit others), a prisoner referred to only as Lucas volunteers for an experiment that could earn early parole. A carefully calibrated procedure is prolonged by a vengeful guard, resulting in agony, steel hard skin with commensurate strength, and escape.

Back on the streets calling himself Luke Cage, he employs his abilities as a genuine protection business, dealing with the thugs of Harlem. Goodwin leaves the series in good form with a solid set-up and supporting cast, and the decline starts with his successor Steve Englehart, elsewhere very good at the time. There are signs that he might have been here as well, with an offbeat Christmas story, or the idea of Cage heading to Latveria to collect a $200 fee from Doctor Doom. Yet as related in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, he’d splice his action with character-building sequences, which would be ignored by Tuska who didn’t want to draw them. Truth be told, he didn’t fancy much other than delivering generic pages. Almost forty when he began working on the series, Billy Graham wasn’t the accomplished storyteller Tuska was, but at least his version of Cage inhabited a world that had backgrounds and resembled Harlem.

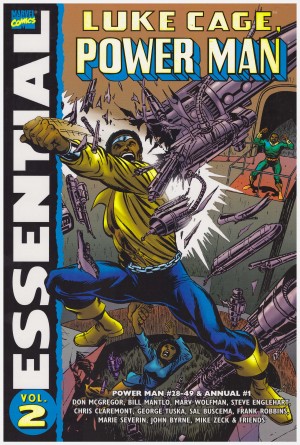

Tony Isabella and Len Wein write the remainder, but there’s very little spark present, and the return of Tuska to the art saps most of it. It may well be that his attitude to Wein and Isabella’s scripts was the same as his view of Englehart’s. The highlight of the final ten chapters here is a tale in which the villainous Power Man arrives to bring Cage to book for taking his name.

A problem throughout is that Cage’s strong characterisation as an urban hero plays out against a constant stream of super-villains as he’s treated editorially as just another superhero. Oddly, though, inappropriate they may be, with dumb names and dumb costumes, but the likes of Diamondback, Chemistro, Black Mariah and Commanche are characters that could be updated for modern use.

Volume two sees a slight upswing in quality, and for those just not able to take advice, the first sixteen issues reprinted here are also available in colour as a hardbound Marvel Masterworks edition, while the remainder are found in the second Luke Cage Masterworks collection. Alternatively everything is reprinted in colour in the bulky paperback Epic Collection, Luke Cage: Retribution.