Review by Frank Plowright

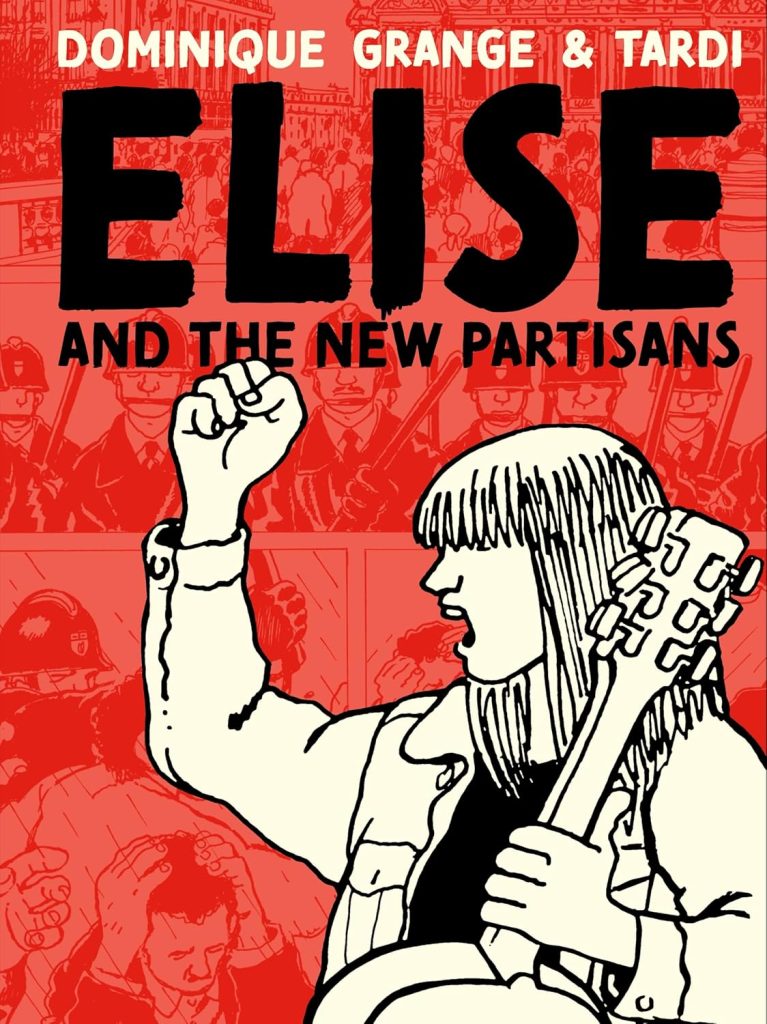

Paris has historical precedence for successful rebellions, and May 1968 saw a populist uprising by French students that led to civil unrest throughout the country. Elise and the New Partisans deals with that rebellion and the period that followed and is described by Dominique Grange in her afterword as neither fact nor fiction. Perhaps even after all these years admitting to involvement in some events would be too dangerous.

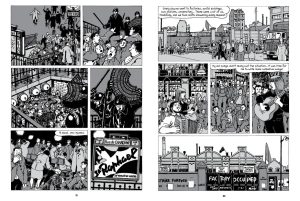

It opens with the infamous Paris massacre of 1961, horrifically depicted by Jacques Tardi, the beautiful Parisian architecture witnessing abject brutality and casual, state sanctioned murder. It wasn’t until 1998 before the police chief responsible was prosecuted, and then for his collaboration with Nazis during World War II. Tardi’s art is wonderful. There’s no hint of deterioration in the work of an artist now in his late seventies still maintaining a prolific schedule as his packed and detailed panels hone in on the essence of historical activity and provide vivid storytelling for the personal elements.

The central character is Elise, Grange’s avatar sharing many elements of her background. She’s politically awakened in the late 1950s by a Jean Brodie-style teacher opening the eyes of her pupils to the wider world, and Elise’s activism begins. She narrates her backstory during an extensive recovery after being accidentally injured by unstable explosives stored in a residential flat in 1972, and it’s a dispiriting catalogue of the social iniquities post-war France.

Elise is a minor celebrity in Paris and becomes involved in relatively small, but terrifying incidents as the country slips into disarray in 1968. Police brutality continues to go unsanctioned, and in the pre-internet era news distribution is selective. Unlike others, Elise’s involvement continues past the 1960s to the extent of taking factory jobs in order to agitate and report on conditions. Grange is good at highlighting the schisms between assorted left wing factions, their naivety in adherence to Maoist doctrine and how the eyes of the general public were closed when it came to inhumanity. However, by this point any sense of story is reduced to being led by the hand from one protest to the next interspersed with a few personal moments. While the minor details differ and prevent tedium, the bigger picture is repetition.

The result is a faithful documentation to warm the hearts of anyone who also participated in the era’s movement for social change, occasionally tipping into romanticising, but however worthy, it’s unlikely to hold the interest of a younger readership. A dozen pages of Grange relating her treatment during arrest and a subsequent jail sentence briefly restores interest for having a personal perspective beyond the repetition, but it’s a false dawn.

Grange’s activism and brave willingness to place herself in unpleasant situations and danger for the benefit of others makes her a better person than much of her audience. However, her recounting of those times weighs heavily on Tardi’s participation for its appeal.