Review by Ian Keogh

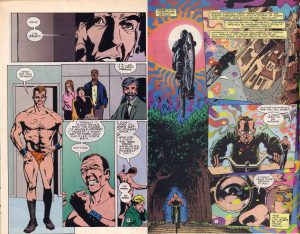

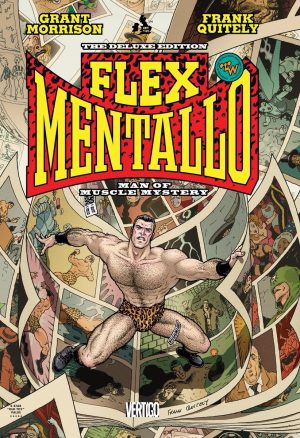

Down Paradise Way was the first selection of Doom Patrol stories by Grant Morrison where he’d had the confidence to foreshadow future stories. He introduced a heady brew of connections leading to revelations about Flex Mentallo, including, but not limited to, the disappearance of Flight 19 in 1945, the first words spoken on the telephone, the men in black and communication with the dead. The result extrapolates around the Charles Atlas method of bodybuilding, serially advertised in the mainstream superhero comics from the 1950s to thelate 1970s. Morrison and Richard Case reproduce the advert’s panels, but their departure occurs by taking the ‘hero of the beach’ lettering randomly placed above the hero’s head in the original ad’s final panel as an actual effect that manifests when Flex strains to the utmost. In his prime he attempted to change the shape of the Pentagon into a circle, but can no longer remember why, and his failure not only wiped his memory, but public knowledge of a once great superhero.

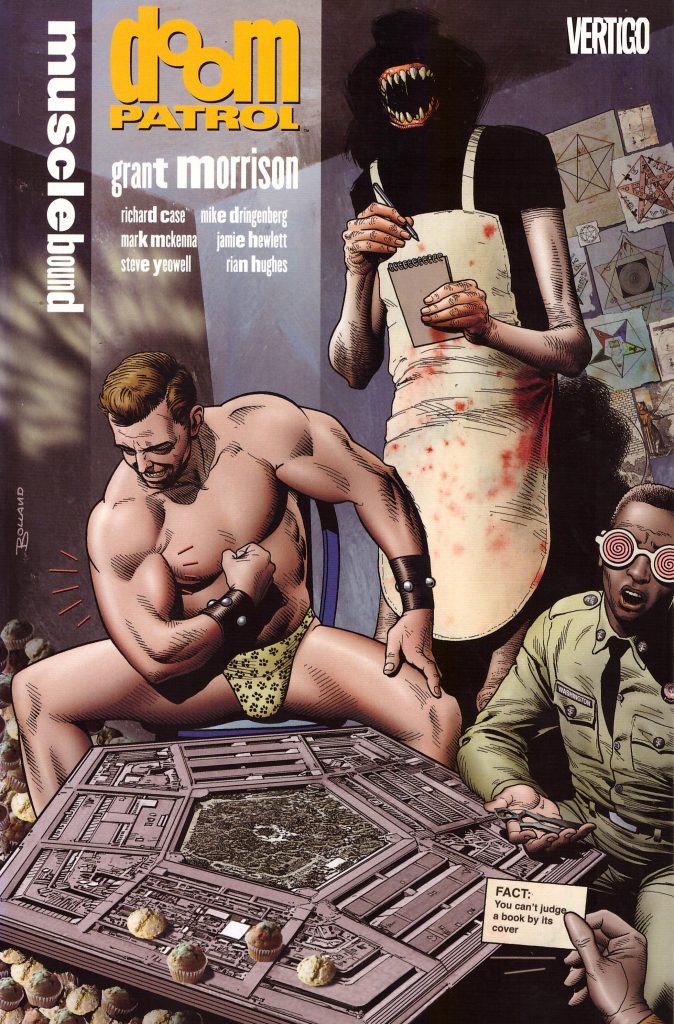

There have been artists other than Case who’ve drawn Morrison’s Doom Patrol, but never so many in a single collection, even discounting the final chapter here being a fiftieth issue celebration. Mike Dringenberg and Steve Yeowell (sample art left) each take a chapter of the Flex Mentallo story, and Vince Giarrano, strangely absent from the cover credits, draws the Punisher pastiche of ‘The Beard Hunter’. Yeowell’s are the strongest contribution, but on the fiftieth issue we have the completely contrasting, but equally effective pages of Jamie Hewlett and Rian Hughes, and Case inking his own pencils is an improvement on his work inked by others. Daniel Vozzo’s colouring also rises to the occasion on Case’s sample page.

Musclebound is slightly weaker than Morrison’s earlier Doom Patrol. In the afterword to the first volume he noted that when considering the series he generated enough plots to occupy every issue from 18 to 63, but then that’s the hyperbole he sometimes comes out with. It feels he’s straining at times, echoing what came so naturally to begin with, and to some extent duplicating the tone if not the content. The conceptual density is still present, but not as convincingly, and the writing is structured more like a traditional superhero comic than before. Willoughby Kipling, not his most fulfilling character the first time round, is back, as is Mr Nobody, now with a new Brotherhood of Dada, refreshed and the best in the book, and Morrison begins to explore ideas of sexuality now permitted by the Vertigo imprint. It’s among several elements that may have been groundbreaking in their day, but haven’t dated well. The satirising of American patriotism seems obvious now, as does some of the comedy. The funniest section is right at the end, where Morrison applies captioned descriptions of odd and previously unrevealed Doom Patrol cases to accompany illustrations by several of the contributing artists along with Simon Bisley, Brian Bolland, Duncan Fegredo and Paul Grist.

The Brotherhood of Dada survive to spread more madness in Magic Bus, and that, this and all Morrison’s other Doom Patrol work can also be read in the oversized hardcover Doom Patrol Omnibus or as Doom Patrol Book Two.