Review by Ian Keogh

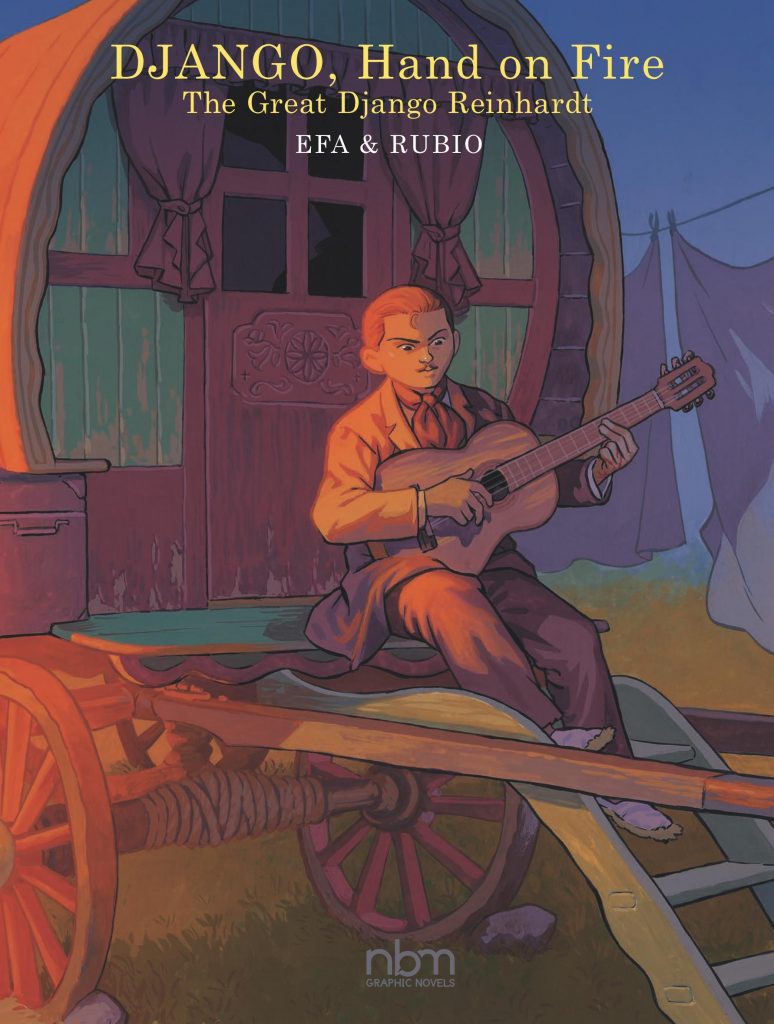

Django Reinhardt is one the greatest ever jazz guitarists, hugely influential both in popularising the form in Europe and in showing how guitar mastery could be achieved with injured fingers.

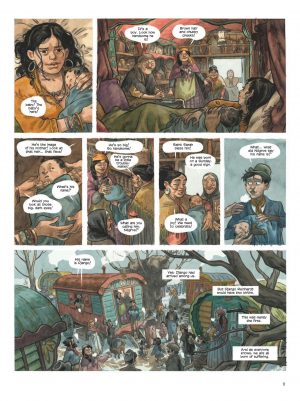

Integral to Reinhardt’s development was the gypsy culture he was born into and grew up in, and Salva Rubio’s biography begins by spotlighting that, although he takes a rather sentimental approach. We’re shown a mischievous child in storybook capers, although picked on for the absence of his father. These pages are beautifully drawn by Efa (Rickard Fernandez) in a lush storybook style, with richly drawn characters and locations. He maintains that polish throughout, with expressive people, and a refined sense for delicately applied watercolour.

Being given a banjo as a child is Reinhardt’s salvation. He’s a natural talent and we’re shown how a determination to master the instrument pulls him away from initial steps into delinquency. He has such an intuitive ear for music that he’s able to reproduce a tune heard through the walls of a club he’s not allowed into because he’s too young.

Throughout events recalled here Reinhardt lived among his Roma community, and the customs and practices are well conveyed, Rubio noting how some are restrictive and formal, yet marriages can be dissolved with hurtful simplicity. Rubio’s chronology concentrates on the early years, covering all essential moments of Reinhardt’s progression and acceptance, showing well how his only loyalty is to his music, and that he’s so prodigiously talented that no amount of poor treatment on his part reduces his demand. The crisis point and wake-up call is a caravan fire in which Reinhardt’s hand was burned so badly the supervising surgeon recommended amputation. Some might find the dual meaning of the title a little distasteful, referring literally to Reinhardt’s injury and allegorically to the speed at which he could play.

Rather than tell the story with narrative captions, Rubio puts words into people’s mouths. Whether down to Rubio or Matt Madden’s translation, the dialogue often rings false, narratively convenient, but clichéd and stilted, giving the impression of a staged presentation. Because that’s a constant background it distracts from what’s otherwise an understanding and nuanced biography. Rubio doesn’t spell everything out, showing instead of explaining the cuts on fingers accompanying constant banjo practice, and how although it might have seemed tragic at the time, the injuries sustained in the fire made Reinhardt. Without them his arrogance and failings would have resulted in a very different life. There’s a suitably mythical quality to the realisation that injuries can be overcome, the one moment where the feeling of staging shines bright.

Reinhardt’s life is full of unknowns and contradictory details, so in an extensive and very readable essay at the back of the book Rubio address his sources and some of the choices made in producing Hand on Fire.