Review by Andrew Littlefield

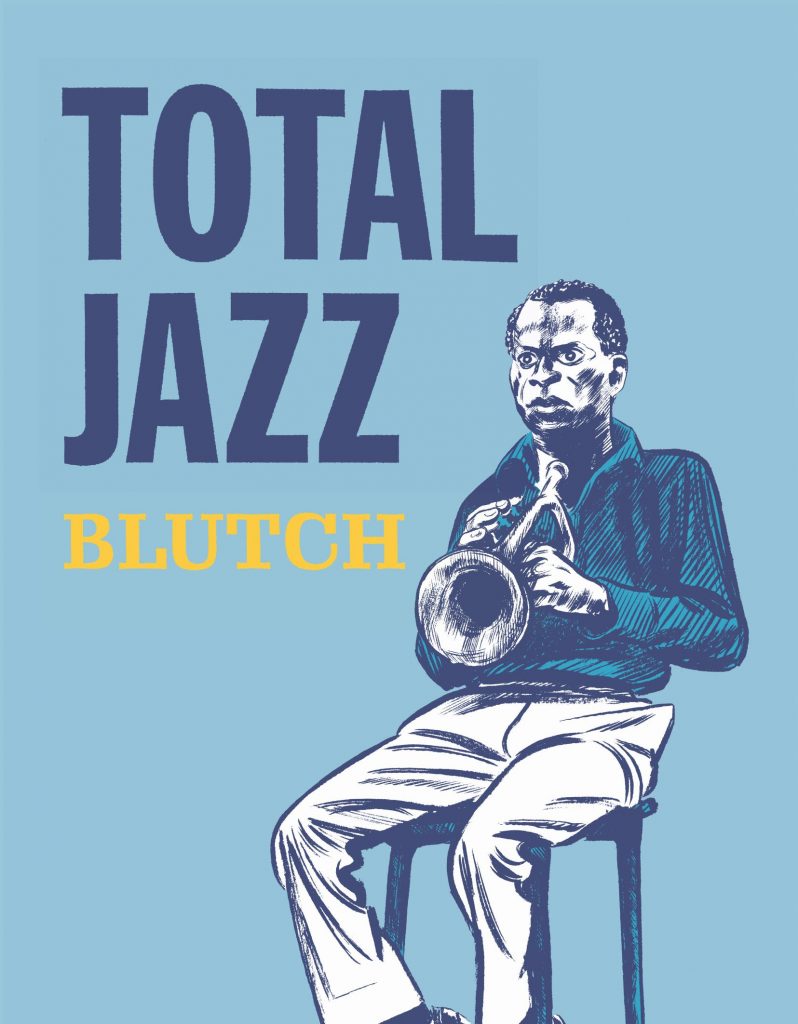

The cover to Total Jazz, by the French cartoonist Blutch, gives a stark portrait of the trumpeter Miles Davis. As a drawing, it’s quite similar to the famous photo on the front sleeve of the Davis album Milestones, recorded in New York, January/March 1958. Just a few months prior to that, in December 1957, Miles had been in Paris, improvising a set of limpid themes for director Louis Malle’s thriller Lift to the Scaffold and enjoying all the respect and attention that the French commonly paid to visiting American jazz artists of his stature (Blutch dramatises this American-Jazzman-in-Paris experience in a one-pager called ‘My Parisian Life’). All of this is to say that first and foremost, Total Jazz belongs to a long tradition of French appreciation of, and connection to, jazz in its many varieties.

Despite the ‘realness’ of the Davis portrait on its cover, Total Jazz is far from a straightforward piece of jazz biography or history. Readers familiar with So Long, Silver Screen, Blutch’s graphic novel meditation on cinematic form and feeling, will know not to expect the literal. This is a writer/artist who likes to dance around his subject, to creep up on it sideways and crabwise. The book begins with a Native American romance (or ‘An Apache Operetta’) that doesn’t have any actual jazz content at all, but functions more like an overture, and then from there we’re presented with a series of improvisations on and around a theme, rather than a singular, linear exposition of studio dates, jam sessions, catalogue numbers and the like. One of the book’s longer pieces, about a ‘jazz detective’ who knows the credits for everything and the value of nothing, clearly pokes fun at blinkered obsessives of all kinds – comics critics exempted, surely.

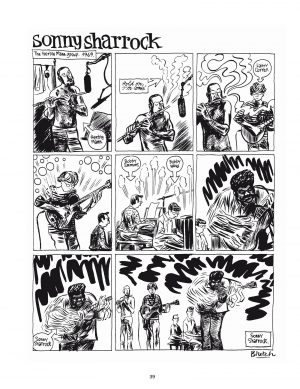

Blutch’s own abiding love affair with this music is one of Total Jazz’s recurring motifs. He has a real fan’s sentimental love for jazz’s great and true romantic narratives about genius and pain and outsiderdom, about effortless cool as both a way of life and as a protective shield against all the racist hangups of the straight world. He clearly idolises the great and good of jazz – we get delightful wordless strips where free jazz guitarist Sonny Sharrock shreds his way off of the page, or where mood maestro Stan Getz suggestively manifests his own name as a creamy swirl issuing from his tenor sax. Sun Ra, Lee Morgan, Duke Ellington and that man Miles again (here sometimes depicted as a scowling but benevolent jazz guardian angel) all make memorable appearances. At the same time, like all true jazz fans Blutch knows that you have to have the bitter with the sweet – Cecil Taylor AND Bill Evans – and a number of the strips in Total Jazz are more clear-eyed, even kind of blue about poverty, artistic compromise, human failings and mortality. To borrow a title from Charles Mingus, it’s definitely a self-portrait in three colours, at least.

Comics, unlike jazz, are not an especially improvisational form. The arrangement of a narrative into sequential frames requires planning, construction. Spontaneity in Total Jazz comes from the freshness of Blutch’s images – the beautiful freedom of his work with the brush, or the dense, frenzied cross-hatching of his pen lines. Here the effect can be as joyful and liberating as the very best jazz wailing.