Review by Frank Plowright

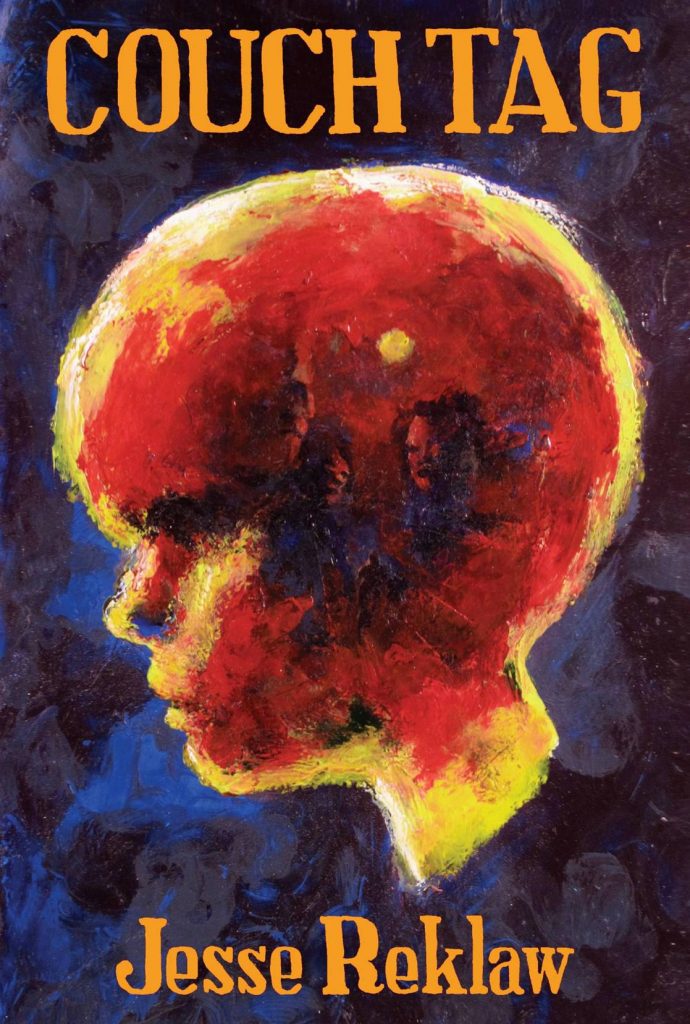

Anyone coming to Jesse Reklaw’s autobiographical Couch Tag without advance knowledge is in for a hell of a surprise. Hints of what follows are in an opening chapter titled ‘Thirteen Cats of my Childhood’. It’s as described, but with references in passing to a father who passes out drunk every night, constant changes of address, and a mother seemingly in denial about what happens. Also, few of the cat stories end well. That’s possibly allegory, as neither did Reklaw’s childhood end well.

He sorts his younger life into five chapters, the first four themed, cats being followed by toys and his creative friendship with Brendan. What’s common to each section is the distanced way Reklaw relates what in hindsight he realises are uncommon and occasionally bizarre experiences. Pain and hurt are knotted together with innocent recollections of Hot Wheels cars or a dolls house, reflecting the way children accept most experiences as normal until the realisation dawns that it’s otherwise. The chapters are separated into short sequences, and while not delivered chronologically a broad timescale can be ascertained. Most questions arising early in the book, such as why Reklaw’s parents cut ties with a family whose son was his friend, are answered later. The anecdotes broaden into a cohesive picture as Reklaw trusts the intelligence of his readers to pick up on the causes of behavioural issues.

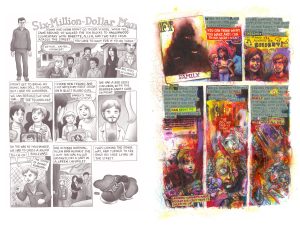

Part of the impact is Reklaw’s careful art, very expressive, and at first glance packed with images of happy children larking about. Indeed, for all the grim revelations, that not an entirely inaccurate picture. However, closer examination reveals the need to read between the lines with the art also, expressions, poses and the intensity of eyes all contributing to an overall melancholy.

Thematically and in terms of length, ‘The Fred Robinson Story’ could almost be excerpted as a separate publication. It’s a chronicle of happier times with grandparents and discovering artistic talent, with the title referring to a long term and multi-tentacled prank centred on a local Fred Robinson. Few readers will have an immediate ancestry as complicated as Reklaw’s, or relations as fractured, but despite the difficulties, this is the most ordinary section, going into too much detail about events common to most families via the conceit of his introduction to assorted card games.

Only for the final section is distanced narrative supplanted by raw emotion as Reklaw lets the atrocities tumble out. It’s the only coloured art, but overlaid with graffiti and scribbles, with the coloured lettering sometimes difficult to make out. As the A-Z narrative makes clear, though, this is our welcome to Reklaw’s real world and the way he often perceives it. The connecting threads are obsessions and Reklaw’s fear of his own intelligence, which when younger he considered limiting and tried to suppress. The graphic and narrative intensity doesn’t make for easy absorption, but it contains surprising revelations based on what’s already been read and re-contextualises Couch Tag. What had been a nuanced formalised recollection is transformed into a disturbing cry for help, reinforced by Reklaw’s subsequent LOVF.

As Reklaw’s life, Couch Tag makes for a difficult assessment. It’s certainly a rare graphic novel that’s uncomfortable for reader and creator. Only he knows for sure, but it transmits as honest and direct in assessing who he is and why he’s that way, often brutally so, and such is the consistency of recollection, Reklaw’s parents should be forced to read it. It awakens the voyeuristic in readers, but is simultaneously an obvious catharsis, and the hope would be that Reklaw’s life is improved for it.