Review by Ian Keogh

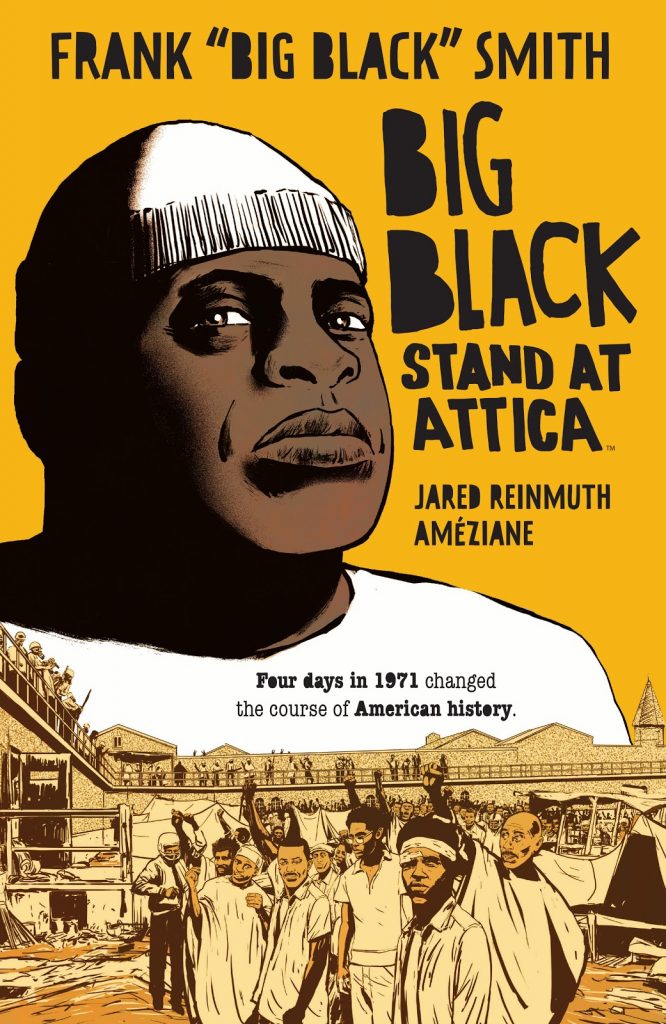

Graphic novels have proved a very effective format for reportage with a social conscience, and this recounting of the 1971 rebellion at New York State’s Attica prison provides a worthy addition.

As lawyer Daniel Meyer’s introduction explains, troops sent to restore order killed 29 prisoners and ten guards. Far from any sense of shame, police then tortured inmates, one of whom was Frank “Big Black” Smith. A single prison officer died from injuries received during the initial uprising, and all injured staff were handed over so their injuries could be treated. Big Black could have left with them, but chose to stay in order to help protect others. Views on what follows are likely to be polarised along the lines of whether prisons are just a means of protecting the public, or whether there’s a duty to promote reform and education to a population who’ve largely never received guidance.

Until reaching the four days of the prison uprising Smith and co-writer Jared Reinmuth avoid a strictly chronological account. The book opens with a page noting the fifteen demands from prisoners organising the uprising. They’re entirely reasonable, and the Prison Commissioner is subsequently seen saying he’s in favour of most. After that we’re shown the beginning of the end as state troopers in helicopters fly over the prison yard just firing indiscriminately into the crowd. That’s followed by New York Governor Nelson Rockerfeller’s self-congratulatory phone call to President Richard Nixon.

Smith doesn’t deny the reasons he was jailed in the first place, armed robbery from people who owed money, and by 1971 he’d served six years. He was well respected by all parties as coach of the jail football team, and well aware of the subhuman treatment prisoners endured. Although not among the rebellion instigators, his standing led him appointed as security chief to ensure hostages weren’t harmed. We’re taken through the four day standoff, then the appalling aftermath. This includes the hypocrisy of the authorities, their attempts to rewrite events in a racial context, then blame inmates for the deaths of officers killed by the troops. Eventually we reach the decades long fight for justice.

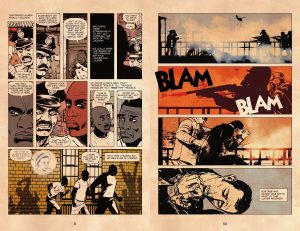

French artist Améziane has an efficient documentary style, distinguishing the main characters inside and outside Attica, and provides effective pastiches of 1960s style Marvel Comics splash pages as chapter separators. He doesn’t tone down the brutality, which would diminish the overall effect, so ensures readers experience each sickening beating. It’s necessary, but doesn’t make for pleasant reading.

Much of Smith’s writing is taken from legal testimony. He lived to see a court settlement reached compensating prisoners, but died in 2004, so Reinmuth shapes his words into a compacted cohesive narrative. It’s a powerful record of events that should provide a lesson, yet the sadness is that conditions in privatised American prisons have deteriorated considerably since 1971, with the companies running them often able to avoid any public scrutiny. It’s easy to speculate that much worse now occurs.