Review by Frank Plowright

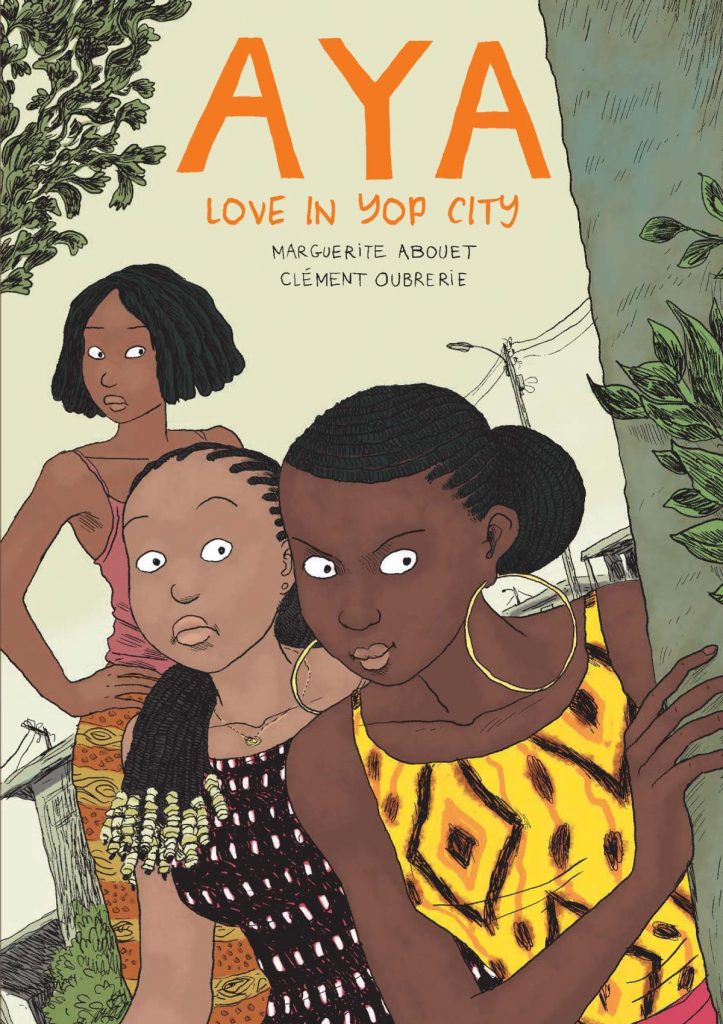

At nineteen Aya has grown up in the Youpogon suburb of Ivory Coast’s capital Abidjan, where in the early 1980s she still lives with her parents and a much younger sister and brother. Life in Yop City showed how her friend Adjoua became pregnant, and the complications that caused with their other friend Bintou. Alternatively, that complete story is available broken down into three thinner graphic novels, beginning with Aya. Love in Yop City translates and combines the next three Yop City graphic novels produced by Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie.

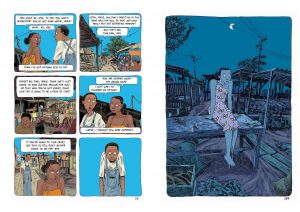

It will need no selling to anyone who’s read Life in Yop City, being a similar mixture of comedy and drama with personality prioritised. Abouet’s cast numbered over twenty when that book ended, and these stories are preceded by two pages of portrait diagrams showing how they all connect. Abouet surprises by starting the story with Innocent, someone she seemed to have discarded when he departed for Paris, but he becomes a major character showcasing the cultural changes experienced by Africans newly arrived in Paris, even back in the early 1980s. There have also been changes in Youpogon, colloquially known as Yop City. Aya is at university studying medicine, Félicité has become famous after starring in an advertising campaign showing her face on billboards all over the city, and Bintou is now running an advice shop, although the idea of that rather drifts away. As seen on the sample art, it’s Aya’s advice that’s more practical, if a little harsh on practically the only kind-hearted man in Yop City.

As well as focussing on what immigrant life holds in Paris, Abouet concerns herself more with the customs of her Ivory Coast homeland, some of which will be almost incomprehensible to a Western audience, but show the cast in shades of grey. It’s primarily the men who behave in ways they’ve been able to get away with for years, although that’s not as universal as before, and while new slugs are introduced, some others behave well, and some manipulative women are also seen. Oubrerie’s cartooning plays a significant part in first defining a character, but once we know them, Abouet ensures that whatever situation they find themselves in, they remain true to who they are, with the possible exception of Moussa, who takes a considerable leap into new territory. She extends the cast still further, and even with over three hundred pages to accommodate them it’s still an achievement to ensure everyone has a turn in the spotlight.

Despite a fair number of scenes taking place in Paris, there’s never any great sense of the times, which are given away by the cars more than anything else. It’s because Oubrerie’s delightful quirky cartooning supplies timeless locations, and the effort he puts into the detail ensures they look like places where people live. And as before, he supplies a great selection of personality-rich portraits and pin-ups.

A new set of secrets infest Yop City, and Abouet weaves dramatic comedy gold from them. She resorts too often to proverbs, a habit that becomes forced, but she puts her cast through even more intensive problems than before, especially Aya herself, as the emotions run very deep.

More recipes, contextualising essays and a further glossary end the book, which concludes Aya’s graphic novels in fine fashion. Abouet subsequently turned her attention to the all ages comedy of Akissi.