Review by Karl Verhoven

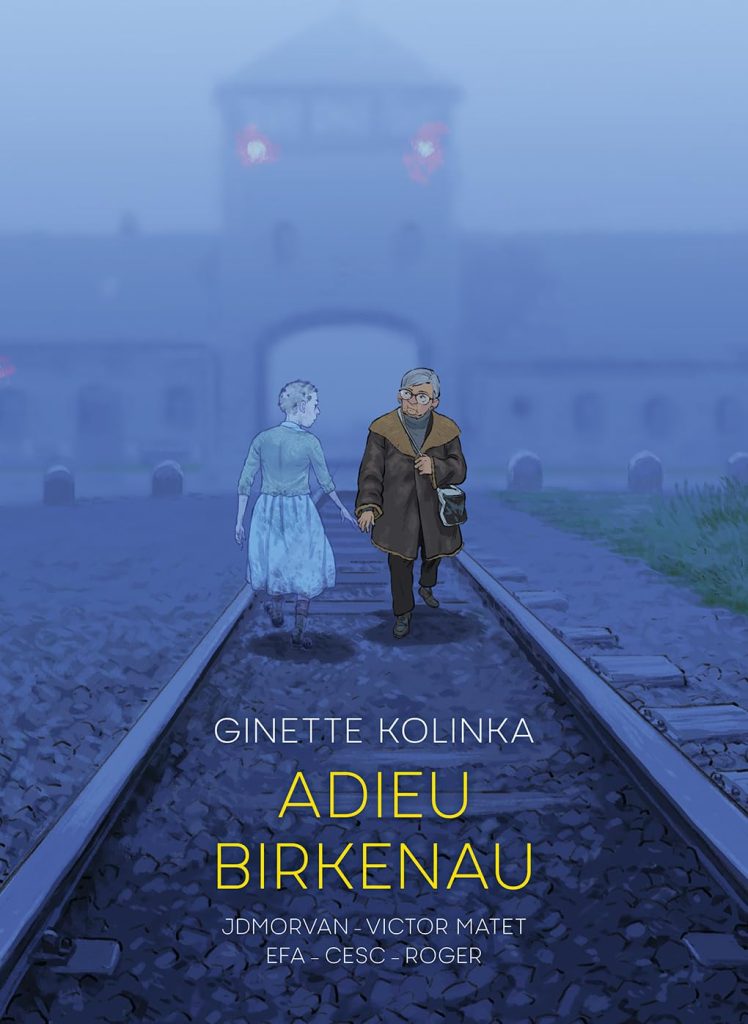

Over recent years graphic novels about the Holocaust have proliferated, but Ginette Kolinka’s story is nonetheless remarkable, both for what she experienced and her life afterward. Veteran writer J.D. Morvan collaborates with journalist Victor Matet to recount Kolinka’s life from personal recollections and evocations of the time. It begins with the childhood assumption of her son that all mothers had numbers on their arms.

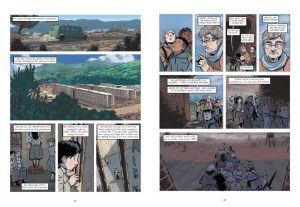

Ginette was the youngest daughter of a large family living in Nazi-occupied Paris during World War II, and although not adhering to the Jewish faith, their ancestry marked them as targets. Adieu Birkenau abounds with little details, first concerning the escalating persecution of the Jewish community, and then with day to day life in Southern France, which wasn’t entirely occupied by Nazis to begin with.

The art is also distinctive for departing from the usual grim depiction of grim times. Fine days are acknowledged with brightness, while Spanish artists Cesc (Francesc Fullana Dalmases) and Efa (Ricard Fernandez) show the young Ginette as generally cheerful, which flies in the face of expectation. Their workload isn’t specified, but it looks as if one artist handles the scenes set in the past, while the other illustrates scenes of Ginette’s later life. Both are accomplished, and artistic restraint prevails, people in distressing scenes rendered as smoky shadows.

Hateful contemporary newspaper articles from collaborators, mix with personal recollections from the 1940s, with those experiences cut between Ginette in her eighties taking a party of school children on a tour of the Birkenau concentration camp. While not as shocking as the events of the past, a sardonic Ginette shows little restraint in her explanations, telling things to the children as they were for her. “From that moment I must have stopped thinking. My brain just shut down.” reveals Ginette on being told in 1944 why the vast chimneys belched smoke, “Not thinking any more might be what saved my life”.

The story weaves around some famous names, bizarrely including 1980s French rock band Telephone, but they never distract from Ginette’s grim experiences, which progress from Birkenau to forced labour in Belsen. It becomes a testament to what’s necessary to survive, and an especially telling moment is the older Ginette’s revelation that she’s never been able to cry since the 1940s.

An extensive section of historical notes and pictures follows Ginette’s memoir, ending with the horrific disclosure that of all her family members who were deported she was the only returnee. The very idea of ranking holocaust stories is offensive, but Adieu Birkenau is more accessible due to Ginette acting as tour guide, offering commentary along with experience. Ginette’s personality provides a stamp of authentication to appalling events. How can some people so easily shed their humanity?