Review by Frank Plowright

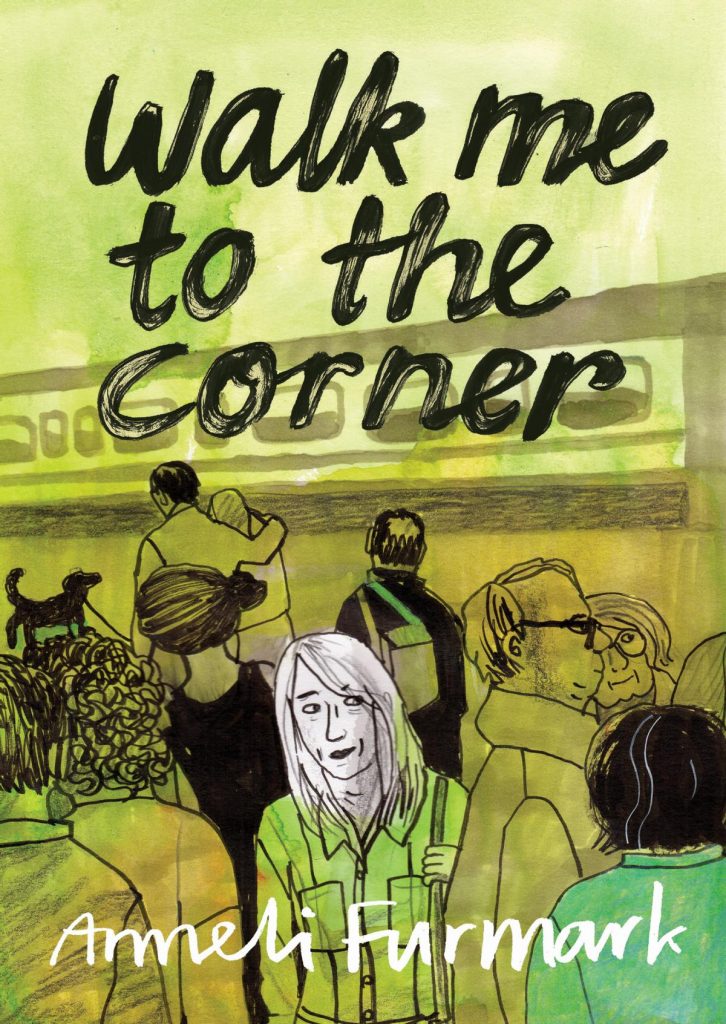

When Elise meets Dagmar at a party she finds herself excited and aroused. It’s completely beyond her experience. She’s lived through to middle age happily married to Henrik and loves him no less, yet is bowled over by Dagmar also. From that Anneli Furmark constructs something as novel as the relationship is to Elise.

Furmark depicts Elise as experiencing the equivalent to the first flushes of teenage infatuation, yet as both parties are smart, professional women this is overlaid with a veneer of intellectual rationalisation. Throughout this she professes no change in her feelings for Henrik, if anything feeling an intensified love for him, while he struggles with fears of losing his wife. Dagmar also has a partner, a woman, and they have children. While the feelings of others are acknowledged and absorbed, it’s always in the presence of Elise, and it leads to a complex investigation of priorities in any relationship, and what’s compatible with them.

While Walk Me To the Corner is a more confident and assured work, the theme of a middle aged woman looking elsewhere for love is also examined in Furmark’s Red Winter, where the infatuation was a younger man. Two graphic novels are hardly a definitive statement, but for a considerable time the repetition is puzzling. Neither story would seem any kind of fantasy as Furmark highlights the pains as well as the pleasure, if anything giving hurt greater precedence. Eventually, though, comparisons evaporate because previously Furmark left much to the reader’s interpretation, while everything is laid out here. While it’s never raised, hanging over everything is the comparative benefits of honesty and deceit in a relationship. Would all parties be happier had Elise never confessed her feelings for Dagmar to Henrik?

Furmark’s art is emotionally strong without being conventionally attractive. Because drama is the central pivot, Furmark ensures that’s seen, boldly using several wordless pages at a time to stress moments of upset or tension, and has an interesting way of honing in on a small detail as a signifier of intimacy or heartbreak. She illustrates a broad range of characters, prominent toward the end when Elise discusses her situation with a number of friends around her age. This is a good scene, one of possibilities unexplored and a sense of Elise being admired for choosing passion above security.

There is a sense of self-awareness about Furmark. She raises the subject of cliché and has a therapist respond, and has Elise identify with Brokeback Mountain and Emma Thompson’s character in Love Actually via the music of Joni Mitchell. Ultimately, though, as the therapist acknowledges, these things resonate because they’re, if not quite universal, then certainly common.

One imagines Drawn & Quarterly will have an uphill struggle marketing Furmark’s work, because the reader who’ll take the most from this is an older woman who’s seen a bit of life, and the suspicion is that they remain a very small percentage of those reading graphic novels.