Review by Frank Plowright

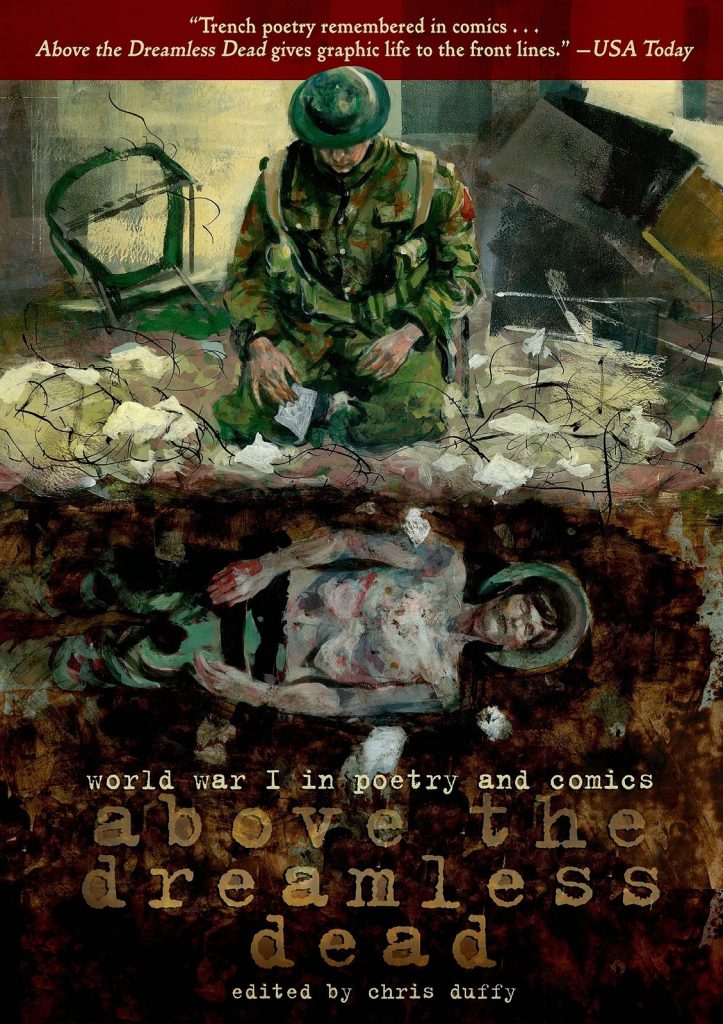

Issued to coincide with the centenary of World War I starting, Above the Dreamless Dead aims at the not inconsiderable target of fusing poetry with comics. As much poetry is about imagery there’s a head start, yet poetry isn’t sequential description, but something more ethereal. Editor Chris Duffy themes the collection around poets describing World War I, all too often grouped together, but as his introduction notes, that’s more an imposed literary convenience than a collection of writers with a shared aim. Being the most famous as poets, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sasson, who did know each other, are well represented, witnesses to horror in contrast to the idealistic militarism of Rupert Brooke.

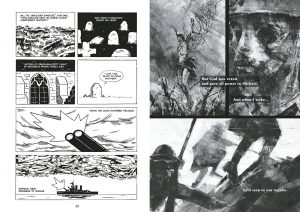

Thomas Hardy and Rudyard Kipling are best known as novelists, but are also highly regarded poets and Luke Pearson opens the collection (sample left) by adapting Hardy’s ‘Channel Firing’, a lament written before war broke out, but when it seemed inescapable. It’s almost pastoral while Peter Kuper adapting Issac Rosenberg’s ‘The Immortals’ features no quiet desperation, just visceral horror. The horror of corpses painted in grey by George Pratt accompanies another Owen poem ‘Greater Love’ adding another level to already heartfelt condemnation. Pratt also illustrates Owen’s ‘Soldier’s Dream’ (sample right) and ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, the truth of the war as opposed to the patriotic lie of the glory of dying for your country. He brings depth and dignity, reinforcing tragedy in stark images.

No house style unites the adaptations, each artist bringing their own strengths, and at the back of the collection they write about how they approached and framed the poetry, which is insightful, particularly in relation to artists whose work is harder to capture visually. Bringing everyone down to earth with an infallible truth, Eddie Campbell comments on the preposterous nature of any modern day artist imagining they can know trench warfare. He illustrates a chilling passage by Patrick McGill, who did know.

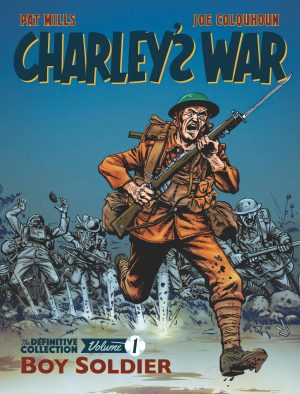

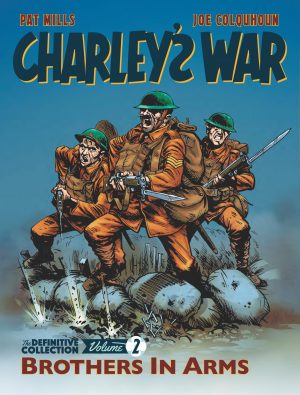

It might be asked why writers such as Kathryn Immonen and Pat Mills are required when the poets supply the text, yet that discounts their ability to think visually. Immonen is acceptably playful and Mills vitriolic in pairing Rosenberg’s ‘Dead Man’s Dump’ with images drawn by David Hitchcock showing life continuing much as usual for a senior officer. Perhaps controversially for some, Garth Ennis takes a step further, adding to Sassoon’s brief caustic condemnation of the officer class in ‘The General’. Ennis also damns cheery wartime clichés and a peace settlement almost designed to reignite war, and Phil Winslade beings the same depth and detail he does to all his projects.

Whether or not poetry appeals, it’s surely impossible not to be moved by this work, and the artists add to already powerful statements. Simon Gane is particularly successful in evoking the bitterness of Oswald Sitwell’s ‘The Next War’ surrounding statues of the fallen with children under discussion. Contrasting the inevitably downbeat tone, every now and then there are pages of Hunt Emerson adapting bawdy soldiers’ songs. As funny as they are, Emerson ensures they still carry a sadness in the finer details. That sadness is evoked in every poem here, from the wistful beginning to the tragic end, many also containing an appeal to an unresponsive God in an attempt to understand the carnage. It’s a stunning anthology.