Review by Frank Plowright

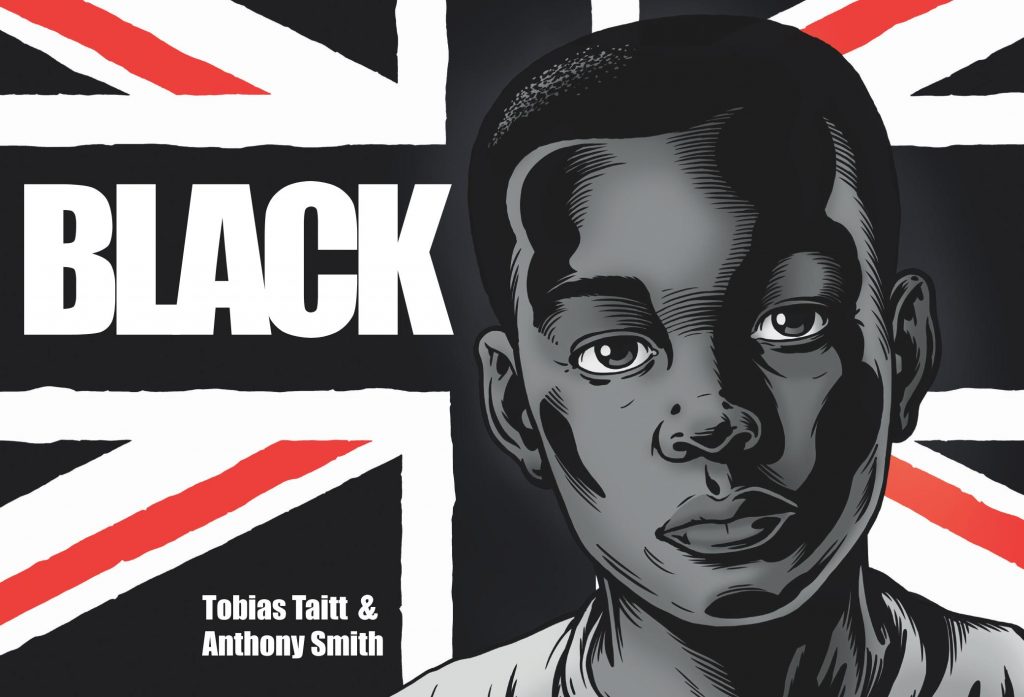

Britain would like to present itself to the world as a caring society, yet it’s institutionalised that a hypocritically turned blind eye ignores so much injustice. Black adapts Tobias Taitt’s autobiography Black Bastard, both published during a major enquiry into decades of abuses in British children’s homes. It’s where Taitt begins his childhood account, consigned to a Catholic institution after his mother murders the man who’s just raped her. In hindsight that’s almost the happy portion of his story.

It’s difficult to know where to begin in marshalling the outrage that builds on Taitt’s behalf. His narrative is honest and matter of fact, dispassionately relating the continuing disintegration of his younger self. The journey he subsequently took could so easily have been prevented by some care and understanding, yet Taitt becomes the product of constant brutality and a system prioritising obedience over all else. His welcome to one children’s home is to be given a kicking by the entire football team as the staff watch.

Artist Anthony Smith takes the same matter of fact approach as Taitt, providing neat and disciplined illustrations to accompany the captions, toning down the more unpleasant incidents to ensure a greater audience. Most of Black occurs in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and Smith nails the period exceptionally well. Those who lived through it will recognise the Ford Transit police vans and accompanying jam sandwich cars, the public telephone booths still a lifeline for many, and the modular plastic chairs, only missing their universal orange colour due to Black being a black and white publication.

While the content is harrowing and heartbreaking, the title is puzzling given the ending. As Black deals with an era when both casual and targeted racism was open and appalling, the title would suggest it plays a part in Taitt’s recollections, but it doesn’t in this opening section. What’s detailed will rouse enough anger on Taitt’s behalf, but it’s strange to reach the final panel of Taitt announcing he’s just discovered he’s black. Although Smith adapts Taitt’s autobiography, it’s a collaborative process with Taitt’s input, so that ending is exactly where both creators chose to break the story, presumably with the intention of picking up with a second volume.

The feeling left at the end is utter, utter horror that even one child experienced what Taitt did in a system that was supposed to care for him. Yet his is just one of thousands of children without a voice who experienced similar treatment in a system with no checks and balances, as if out of sight, out of mind was official policy. Is that system any more fit for purpose today?

On online retail listings pages this is wrongly titled Black Bastard as per Taitt’s novel.