Review by Ian Keogh

In 1995 Tricky Fingers were about to take that step into the big leagues, and their singer Sandro had the charisma, moves and lungs to take them there. It all went wrong. Eighteen years later Sandro’s ambition and dedication have ensured he’s a mega-successful solo act with all the trappings, while his former bandmates have drifted away from music for the most part. Will a weekend’s reunion heal old wounds or open them again?

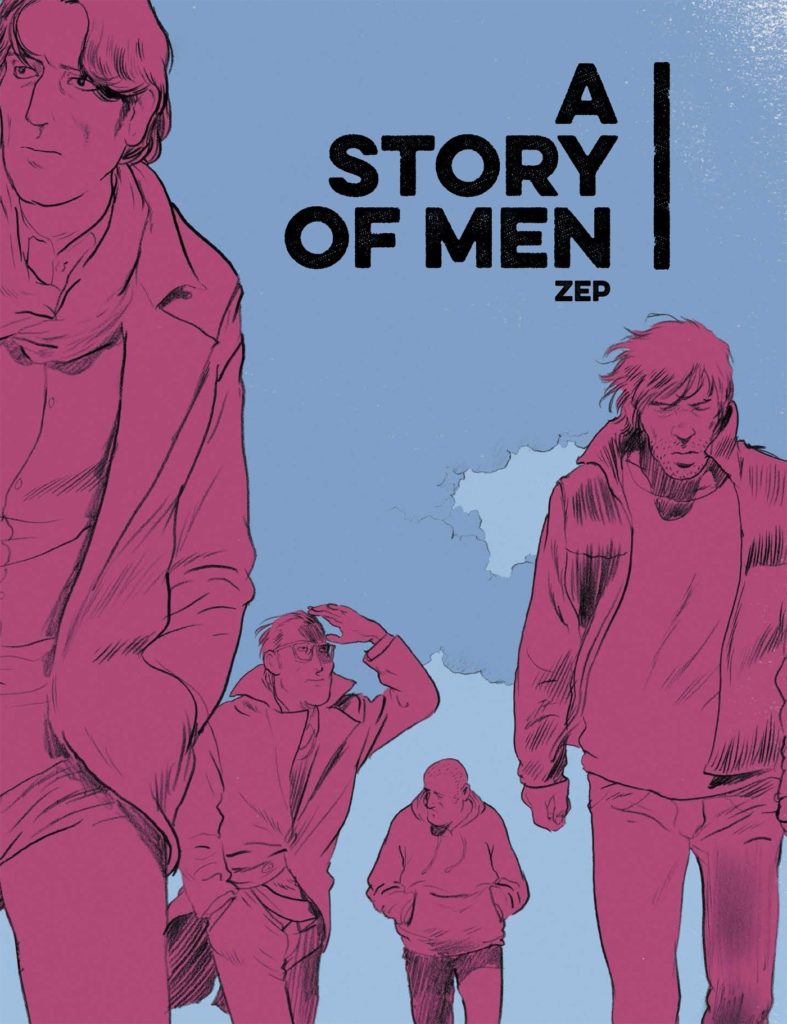

Swiss creator Zep (Philippe Chappuis) is known all over Europe for his gag strip Titeuf (think Dennis the Menace, UK version), drawn as bigfoot cartooning, but throughout Titeuf’s success he’s worked on other projects. These are mainly cartooning, but he also has an adventure style, and A Story of Men is illustrated in an attractive naturalistic cartoon form. He’s not as good, but Posy Simmonds establishes the broad area, and few people match her. The tone requires an illustrative sensitivity that’s well provided as the can of worms gradually squirms open, and there’s a nice visual understatement to what subsequently happens.

Zep opens with a dedication to all the bands he’s been in (Blik Bluk, Cap Lib, Titi and the Rauminets…), and rock music is a theme he’s used in other work, so what’s obviously a personal interest provides a convincing background. However, the title is a more accurate representation than the window dressing. Zep’s abiding theme is how men never deal with their emotional problems, for which the tensions within a band and the different personalities united by music form an ideal exploratory petri dish. Tragedy, jealousy, ignorance and shredded hope simmer under a veneer of appreciation with Zep throwing in funny, but surely slanderous comments to bolster Sandro’s rock god credentials.

A friendly bantering facade between old mates is maintained, Zep’s diverse selection of personalities creating the right chemistry to move the plot naturally, but a key resentment simmers until the final pages, and Zep has an additional bomb to drop concerning it. It’s tied too melodramatically to the awkward anomaly of a dream we’ve already seen, and the redemption it prompts is too convenient as narrative closure. Balanced against that is the likeable way Zep reinforces that the bonds forged during youth have a tenacity and honesty over-riding stature and absence, and his assertion that age doesn’t necessarily indicate change.

A few awkward spelling and grammar mistakes smudge the translation, but the bigger fault is Zep’s. A Story of Men is charming in places, funny in others, and certainly a worthwhile read overall, but drifts rather than grabs, the gentle bonhomie postponing the emotional crux too long, meaning it’s not quite all it might have been.