Review by Ian Keogh

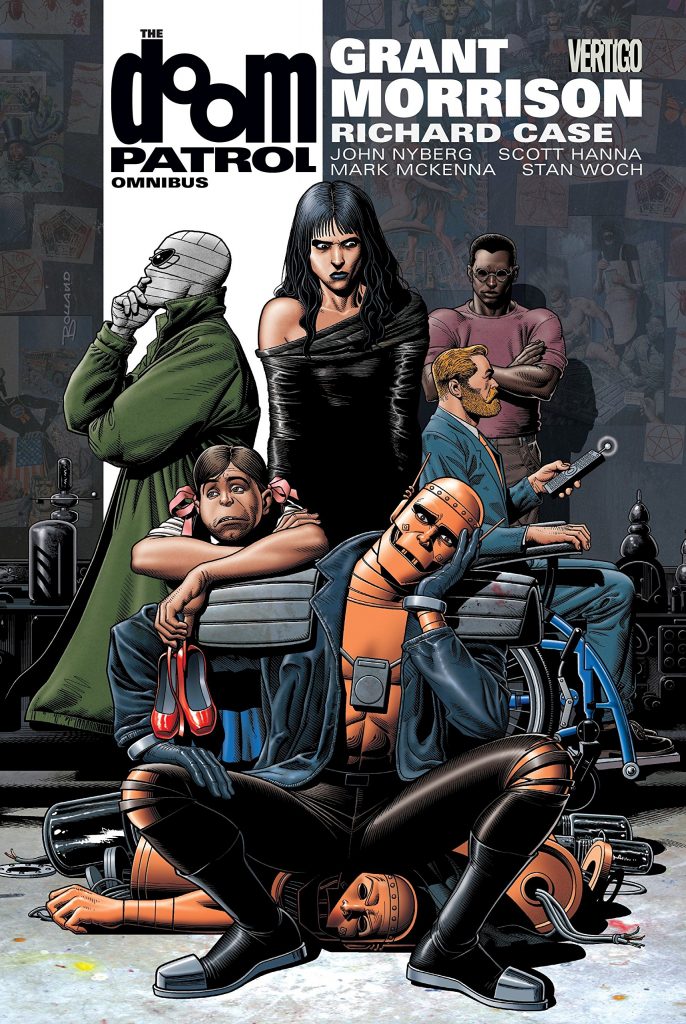

Grant Morrison wasn’t the first to take a surrealistic approach to superhero comics, but before his Doom Patrol no-one had taken it as far or sustained it as long. Handed a failing title in 1992, Morrison prioritised ideas. There’s almost always a superhero battle of some sort, sometimes absurd, but more important is that it’s allied to conceptual notions. It doesn’t look anything like Jack Kirby, but Morrison’s Doom Patrol is similarly infused with ideas, some to be discarded, some with a longer shelf life. Keeping this fresh when aimed at an audience expecting a superhero comic, to begin with at least, required a careful balance, and part of achieving this is the fundamentally ordinary art of Richard Case. No matter how weird or wild Morrison’s scripts may be, Case is almost always there to anchor them in a form of mundane reality. We may wish for an artist more equal to Morrison’s imagination, but would the series have lasted as long with a visionary artist in place? To give Case credit as well, very few of the artists contributing just the single story shine either. Jamie Hewlett is perhaps the best match for Morrison’s approach.

The 1960s Doom Patrol prioritised strangeness, which Morrison returns in spades after a 1990s revival had misguidedly presented a standard superhero team. Morrison has little interest in what he inherited beyond the core 1960s cast of manipulative and irascible team leader Niles Caulder, Cliff Steele (never Robotman) whose human brain operated an engineered metal body, and Negative Man, rapidly reconstituted as Rebis with the addition of a third, female, persona. To this he added Crazy Jane, a damaged asylum resident with 64 distinct personalities, each with their own ability. The other cast members Morrison inherited were kept around, but in background roles until he had a story worth telling about them.

Over the first half of the Omnibus Morrison appears to be throwing in every nutty notion he ever had about superhero comics, presenting a flood of great ideas tossed out and discarded in single panels. The resulting conceptual goldmine is ambitious and innovative, stories featuring absurd characters, the like of which had never been seen in comics before. It’s all very self-aware, but this isn’t intrusive until midway when Morrison has had to pause for thought after the initial creative rush. It’s not all-inclusive, but from the midway point there is the occasional feeling of repetition and writing now structured more like traditional superhero comics, with his final multi-part story almost bereft of inspiration. There are also some dated elements, and some exploration of sexuality that now come across as exploitative. This is however, sifted with some absolute gems, including a great Kirby homage, culminating in the disintegration of the Doom Patrol. And Morrison doesn’t ever receive enough credit for how funny some his material is, and that’s dated well.

Not everything works, but that’s always the case for experimental material, and Doom Patrol has a significantly higher hit rate than most. If preferred, these stories are still available broken down into paperback selections as Crawling From the Wreckage, The Painting That Ate Paris, Down Paradise Way, Musclebound, Magic Bus and Planet Love. Or in larger packages as Doom Patrol Book One, Book Two and Book Three.