Review by Graham Johnstone

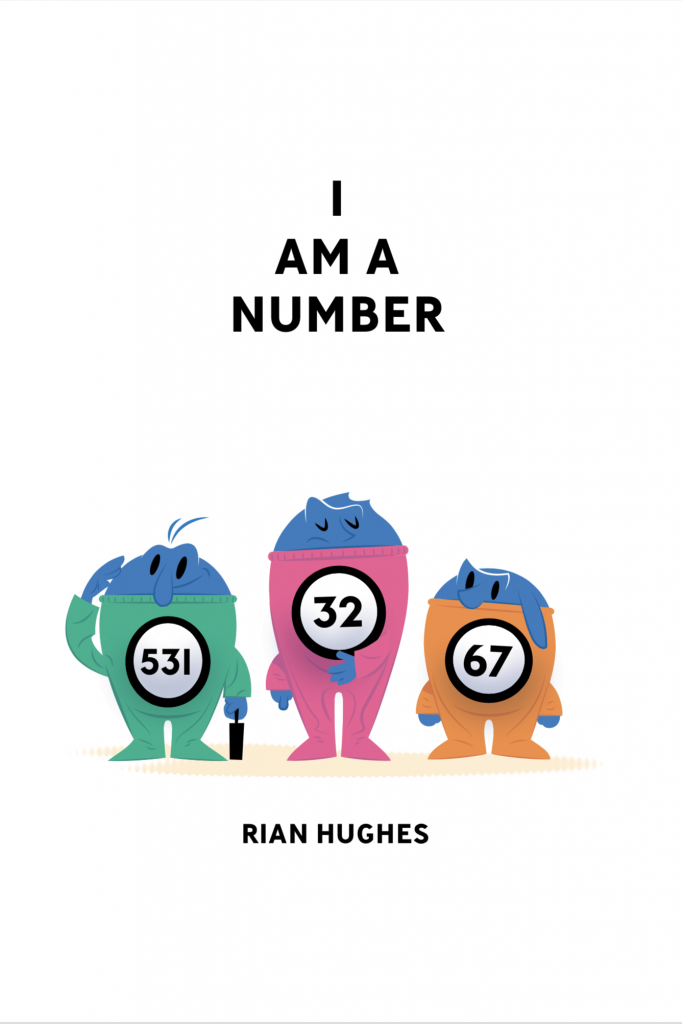

Rian Hughes’ first solo graphic novel is a series of wordless skits on different ideas, representations, and meanings of – you guessed it – numbers.

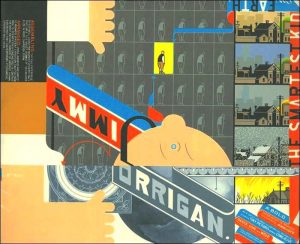

Hughes has made some beautiful comics – a small but distinctive oeuvre. He’s never been a work-for-hire illustrator, subservient to someone else’s vision. Instead he’s worked with writers to realise shared visions. They created a retro-futurist aesthetic, aptly summed up by the title of his collected works – Yesterday’s Tomorrows. The best, and most extended example was his reboot with Grant Morrison of Dan Dare, the 1950s British comics hero, as Dare. His comics also made the most of his skills across the fields of illustration, graphic design and typography, and demonstrate why he’s been kept busy there for 25 years. Many who don’t know his name, will have appreciated his logos for Marvel, DC, and Image titles.

I am a Number, then, is much anticipated in some quarters, so is it what people are anticipating? It’s very different from his other comics, yet distinctively Hughes. He remains a connoisseur of retro styles, and here moves from the 1930s and 1940s, to the 1950s, in a style evoking that period’s animation. The absence of words on the page, combined, with well-designed, and expressive characters also suggest animation, while the plays upon visual representations of numbers highlight his abiding fascination with type as both symbol and image.

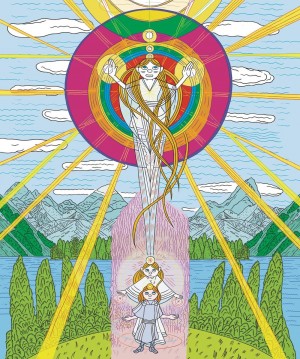

The cover blurb emphasises the idea of numbers as representations of a hierarchy, or pecking order, with the lower numbers being the elite. A boardroom scene provides an example. A character with a lower number is responsible for the profit graph steeply rising, requiring the Chairman to swap number shirts, and so promote the new star over himself. In another example, ‘143’ tries to upgrade his status with some new threads – and can’t believe the deal he’s got on elite number 18, but he’s seeing it in the mirror and doesn’t realise he’s really just ’81’ – until a resentful ’65’ puts him in his place. At times this suggests an uncritically capitalist or meritocratic worldview, and three-digit numbers do seem to be criminals. However, one might equally accuse him of an idealistic view of the opposite ideology, as in Communist, China (sample image), numbers are replaced by equals = signs for everyone – even the leader on the podium. Yet another page, shows model ’29’ strutting on a catwalk, before revealing her dress being made by a worn-out five digit number. Another time numbers show or hide age – a woman coming out of a beauty shop appears to be ’16’, until we look more closely and see a residual ’46’.

Each ‘story’ is only a few pages – hardly more than anecdotes, nonetheless they communicate their points. Stories are divided by a series of single, full-page drawings. These mostly play out cultural associations with numbers – ‘221B’ is a detective in deerstalker, and ’68’ channels that year’s fashions of psychedelia and paisley pattern. There are other fun moments, like when scientist ’71’ creates a portal, out of which steps his alternative world’s counterpart ‘-71′: with tragic results when the two – matter and antimatter – touch.

Hughes’ drawings are stylish, and the rendering pristine to a fault, as work produced in Illustrator software often is. He foregoes traditional line art, in favour of elegant silhouettes, and flat colours unconfined by outlines. With typically three panels to a page, they lack some of comics’ best features: whole page design, and movement effects within the page.

This is a stylish package, though beyond committed ‘Rianophiles’, may appeal more to lovers of illustration and animation, than to comics connoisseurs.