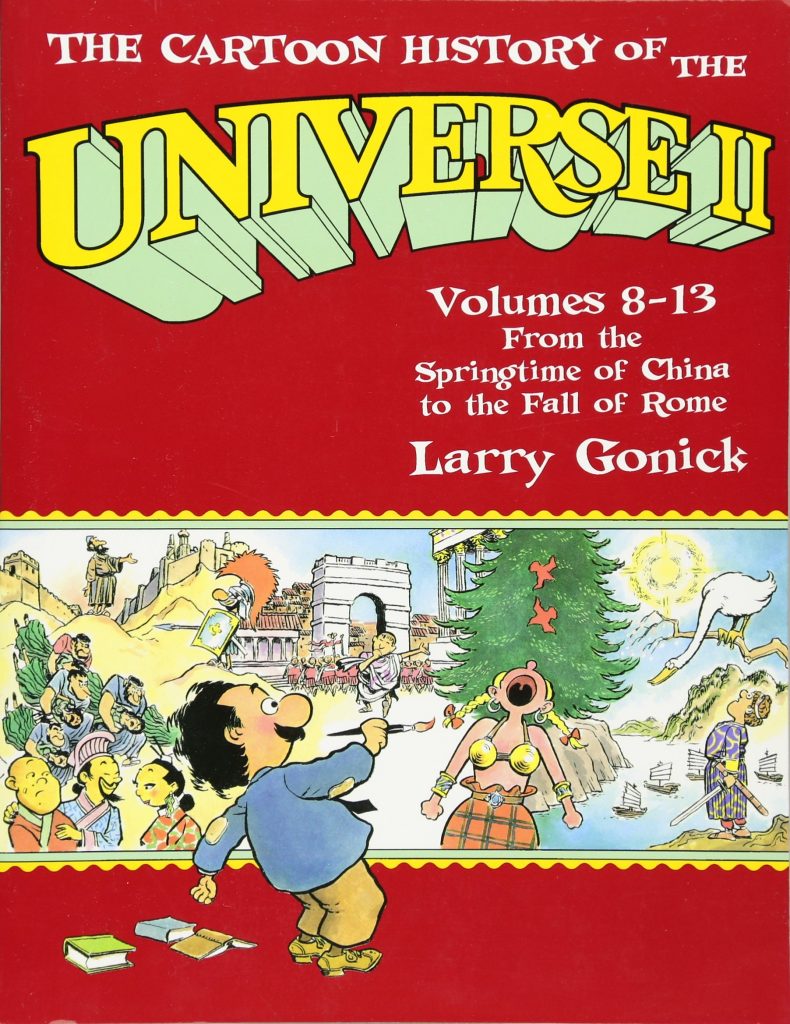

Review by Ian Keogh

Larry Gonick may have subtitled this second volume From the Springtime of China to the Fall of Rome, but it’s in India where he begins this journey. As previously, the sheer wonder is how he compresses so much into so little space, an example being the contracting the epic Sanskrit tale of The Mahbharata into a page and a half without short changing on the illustration. By contrast his précis of the Bhagavadgita features one of the few full page cartoons in the entire 300 pages.

The inclusion of both exemplify why The Cartoon History is so good. Gonick isn’t content just to provide a geological, biological and historical run through, but has a desire to illuminate and explain. The opening sections on the progress of what’s now India and China incorporate pieces on Buddha and Confucius, whose philosophies and thoughts still greatly influence today’s world, which in Confucius’ case has more than an element of good fortune. But Gonick doesn’t stop there. Approaching that same influence, although less known in the Western world, he looks at Mencius, and the I Ching. He’s simultaneously running through history, expounding on social practices then common that are appalling or amazing by 21st century standards. Killing yourself to motivate your successor? Sacrificing your children to mollify the Gods in times of hardship? It’s all here, with no glossing over man’s inhumanity to man. Furthermore, the heroic names of the past are sometimes revealed to have rather hollow credentials, or to have followed their achievements with a dissolute life that eventually killed them (Alexander the Great). Gonick distils an excess of gore without going over the top, about which he even manages a playful comment late on when detailing the destruction of Jerusalem and accompanying atrocities.

As well as being a genial educator Gonick manages to infuse what in some cases would be very dry material with humour to render it more accessible. If there’s not a specific gag, and on most pages there are several, Gonick’s expressive cartooning brings the chronology to life. In case anyone thinks otherwise, this isn’t trivialising the past, but revitalising it. There are incredible stories, such as that of would be ruler of China, Liu Pang and his many attempts to usurp his former warrior partner, or, late on, an adaptation of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The final third of the book reaches the year zero, and Jesus Christ. Steering clear of a bible that’s been altered on many occasions, Gonick gives us Jeshua Ben Joseph, healer, teacher, preacher and rabble rouser, killed for being a political nuisance, as was common at the time, then explains how his followers developed the Christian religion. Gonick sets the scene for volume III by finishing in 564AD with Europe in disarray and the Chinese Tang Dynasty initiating a recovery. Both had been ravaged by illness.

Is there a better way to learn history than Gonick’s presentations? It’s debatable.