Review by Ian Keogh

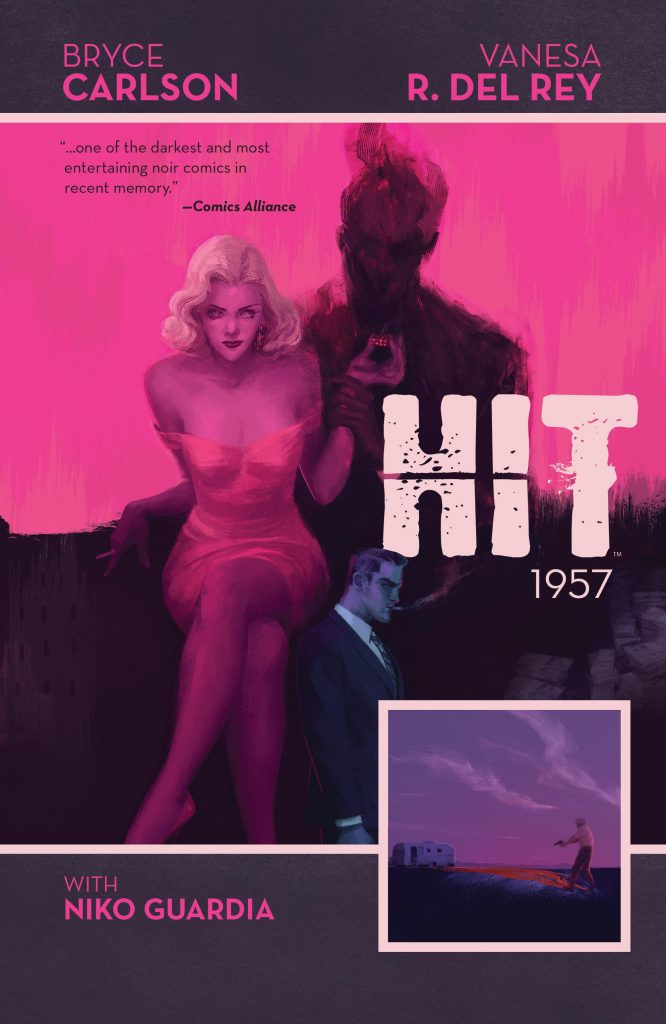

Sequels are problematical beasts. If you ask people what they want the answer is likely to be “more of the same”, yet give it to them and they’ll complain it doesn’t match the first shot. Changing the formula, however, is equally likely to alienate. With Hit: 1955 Bryce Carlson and Vanesa R. Del Ray provided a superb slab of period crime noir. They nailed the cast and promoted the LA locations amid a humdinger of a plot. Can lightning strike twice?

LAPD Detective Harvey Slater has an out of hours career. He and his vigilante partners cruise the city shutting down gangster-run clubs, with no concerns about killing individuals they consider too deeply connected to the mob. They’ve escaped attention for several years, but now Internal Affairs is taking an interest. That’s not Slater’s only problem. There’s a particularly gruesome serial killer on the loose, his relationship with his partner is deteriorating, and he’s also learned his former girlfriend, the one who left him high and dry, has been abducted and taken to Las Vegas.

Carlson works around the characters who survived 1955, and cements in the gaps in both Slater and Bonnie’s backgrounds. The heart of matters is how some people can never change. Of that group some accept what they are and accept the consequences, while others kid themselves on while repeating well trodden patterns. The result is a good noir story, but one which fails to match 1955 by a distance. It’s neither as elegant or as taut, separate investigations pulling the story apart rather than stitching it together, and the hidden in plain sight resolution to one plot strand is gratuitously contrived. The characters still work well for the most part, but much of 1957 reads as if it’s closure, filling in gaps, rather than telling a new story.

That 1957 doesn’t match 1955 is down to Carlson. Del Ray does the same creditable, character-building job as previously, although has less scenery to work with. The looseness and storytelling remains great, and she distinguishes the cast well, and as the sample page shows, the involvement of Las Vegas affects the colour scheme.

As previously, Carlson provides a text epilogue filling in on events that it’s not essential to know, but the consideration in supplying it displays an investment in the series. Had this been the opening Carlson/Del Ray collaboration, pats on the back would have been due for a promising début, but they’re victims of their own creative success, with the consequent raising of the expectation bar. Given the dip in quality, under other circumstances the advice would be to read this before 1955, but doing so would also lessen the reading experience of that earlier graphic novel. It’s a shame. This is by no means poor, but it fails to match expectation.