Review by Ian Keogh

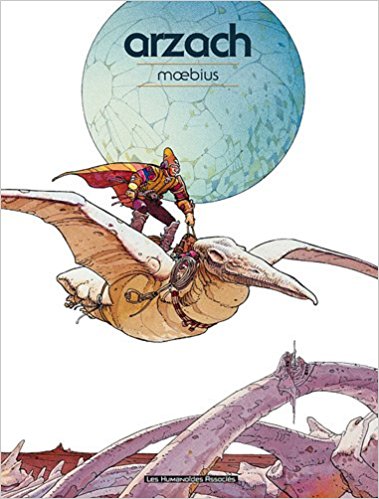

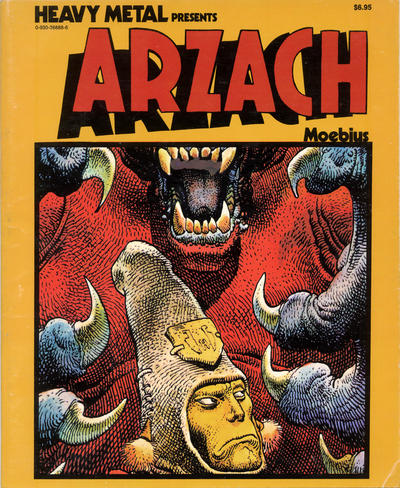

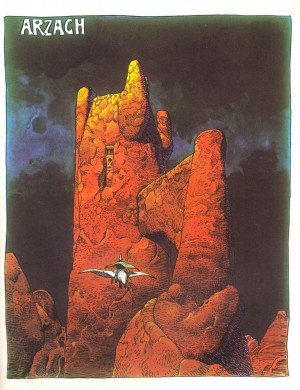

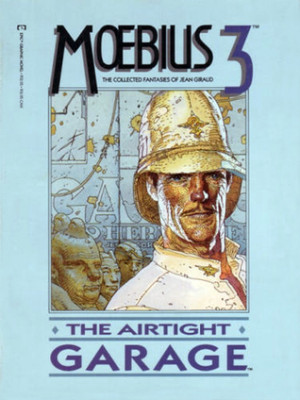

Arzach was a complete game changer for comics, both in France when it first appeared in 1975, then again when it was among the contents of the first issue of Heavy Metal in 1977. At the time he produced the first story Jean Giraud had a dozen years of traditional comic illustration behind him, primarily on the Western series Lieutenant Blueberry, and was looking for a new way to express himself. The result was an eight page wordless fantasy strip in which a distinctively dressed man riding an overweight flying pterodactyl through a distinctive rocky landscape notices a shapely young woman getting dressed. The ending is feeble, but the remainder has a mesmerising air of tranquillity that was unique at the time, as if an improvisation around dreams. It transcends the years since as an otherworldy piece of fantasy that opened new doors. Giraud reactivated an old alias of Moebius to sign the strip.

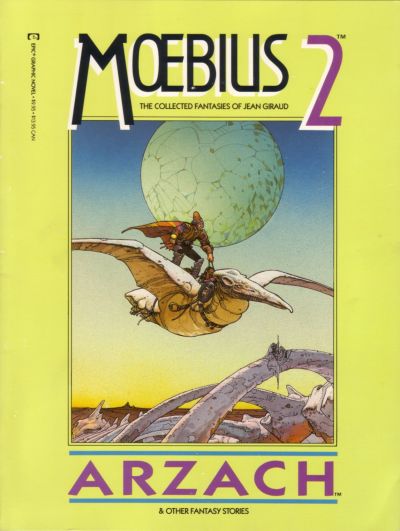

There’s a playful air about the remaining three strips collected in the first American publication, with Moebius changing the name of his strip on every occasion (to Harzack, Arzack and Harzakc). It’s both viable and redundant to ask if this is the same character, or others of his ilk, as Moebius explores the depths of his imagination. Fantasy is the connecting thread, but it’s the art and mood that matter, not any narrative element. The illustrations range from relatively simple flat landscapes with abstractions, to dense battle panoramas, delicately drawn in ink and as far as possible avoiding points and straight lines. Almost everything is curved, corrugated, mottled, and lumpy. The meditative mood induced by the lack of dialogue and sound effects has proved as enormously influential as the unlocking of imagination. In later years Moebius would ponder the symbolism of recurring curved escalating objects.

These four core strips comprised almost the entirety of the first American Arzach publication, the remainder being a handful of brief black and white strips and illustrations, and have formed the heart of any subsequent re-issue. Returning to the world of Arzach in later years Moebius tinkered with his formula to include dialogue, so for anyone concerned about following a story, the 1992 collection published byEpic is advised, although copies are now expensive. At the time of publication the final story, a sort of fairy tale for Giraud’s daughter, hadn’t seen print in Europe. Also featured are ‘The Detour’, a more whimsical interpretation of the Arzach concepts with Moebius himself at the centre of events, produced in order to sell the idea of a TV show based on Moebius’ concepts, and three short pieces. None of these feature Arzach, but have stylistic similarities of encounters with the unknown. For all the beauty of the art, and it’s very interesting to see a Moebius strip influenced by Richard Corben, adding dialogue is very much a mood-destroyer. ‘The White Citadel’ could have much of the dialogue, especially over the opening pages, removed to no great detriment.

While Moebius is again out of print in English, his works remain available in France, and as the essential Arzach remains the four original silent strips they’re viable in any language. Pick up a French version and admire the art over the remaining content.