Review by Frank Plowright

While the 20teens have seen a massive increase in the number of women reading graphic novels, there was a previous era where they consumed considerable quantities of comics. From the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s romance comics sold in their collective millions. Never slow to jump a bandwagon, Marvel published their fair share, and, credit to them, attempted a revival in the late 1960s, even if their ideas about women of the era were dated and skewed. Marvel Romance is a glimpse back into those eras, reprinting material from the period of 1960-1972, with the latter three years covering half the content. Reaction will occur along a spectrum, with the most strident viewing the material as a catalogue of patronising suppression at best and offensive views at worst, sliding all the way down to those considering it a selection of amusing timepieces reflecting the era. Actually, since only one of the 24 stories is credited to a woman (Jean Thomas) it’s more likely a reflection of the outmoded perceptions of middle-aged men (primarily Stan Lee, others unknown) who wrote the remainder.

Anyone likely to be offended by 1960s romance stories will have their expectations confirmed. Collectively they provide a message that a woman’s (or girl’s) life is only validated once they’re attached to the man of their dreams, and often keeping a home for them. Techniques required to ensure this include subterfuge, dishonesty and manipulation. Thomas’ story is no better in this respect, and narratively poorer than most, but at least she defines her protagonist as an intelligent woman. In the 21st century it’s to be hoped that the stories can be seen as harking back to an era from which we’ve greatly moved on.

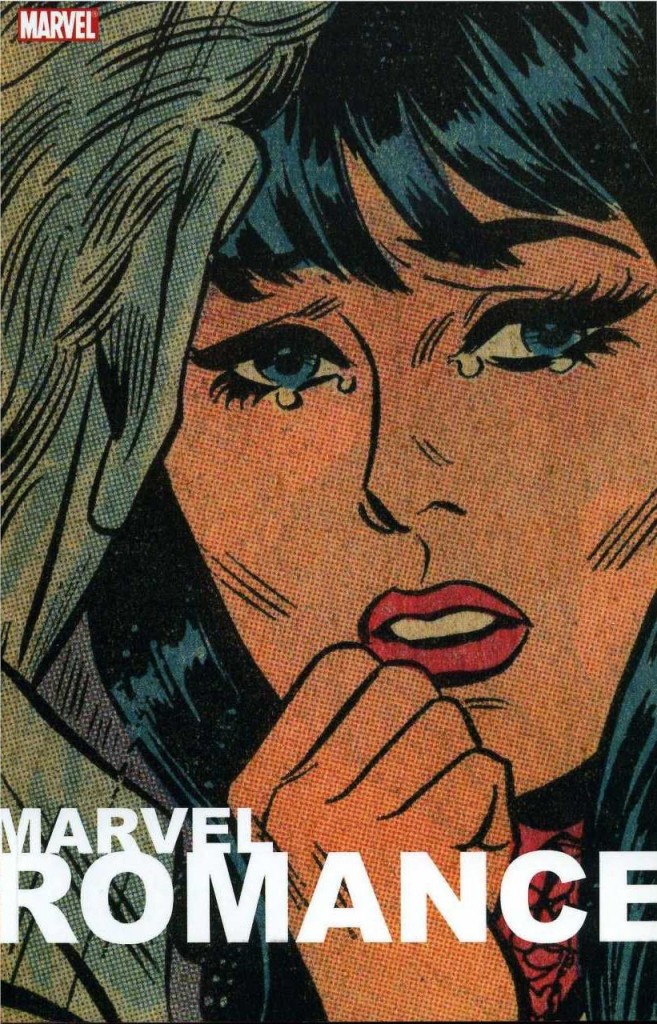

That leaves the art as the attraction, and it’s fantastic. The Lichetenstein style cover displays some consideration has been applied to the selection. There’s a sea change when the content leaps to 1969. The early 1960s pages are traditional, and universally elegant. Vince Colletta, later controversial for what he didn’t ink, gives many different pencillers, some still unknown, a beguiling polish. The Grand Comics Database now credits one of the anonymously illustrated strips to Joe Orlando, and ‘Please Don’t Let Me be a… Spinster’ has a great visual appeal from the opening in a rose garden to the refined characters. In both eras the artists paid careful attention to fashions, and we can be grateful now for the excesses of the early 1970s.

Artists from Marvel’s superhero titles applied the same types of layouts to romance material to create great looking pages. It’s a catharsis for some who earned their living drawing superheroes, but who weren’t fond of the genre. Don Heck inked by John Romita is stunning, John Buscema (sample art) is liberated, and Gene Colan spectacular (and unrecognisable as the same artist credited with a 1962 strip). One horrible misfire is the young Jim Starlin inked by an unsympathetic Jack Abel, but we have the glory of a Jim Steranko strip that takes the possibilities of pop art and late 1960s fashions to weave something still unique. For American comics at least. For British readers it’s reminiscent of the Spanish artists who contributed to weekly girls comics in the 1970s, with its fusion of light effects, minimal lines, and less black shading.

For those who want to read the original strips, this is the book, but there’s an alternative. Marvel Romance Redux presents most of the same art (not Steranko) with ironic modern day dialogue.