Review by Tony Keen

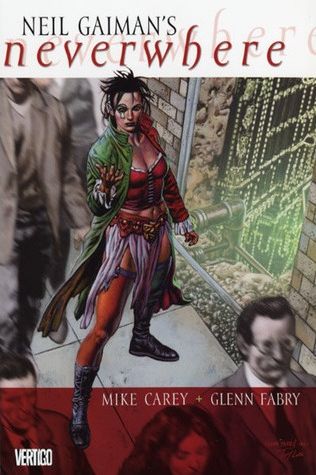

Given that Neil Gaiman first made his name in comics, it might seem surprising that it took until 2005 before someone adapted his 1996 fantasy TV series and novel Neverwhere into the graphic format. Gaiman’s old friends at Vertigo took on the role of presenting a new version of his other London, where the people who fall through the cracks find a home. The plot is a variation on a common Hollywood trope – boring office drone Richard Mayhew is on the way to marrying inappropriate fiancée Jessica, when Manic Pixie Dream Girl Door falls into his life. He ends up joining her on her quest to find out who killed her parents and why, in a fantastic London of strange individuals, where many characters share names with stations of the London Underground.

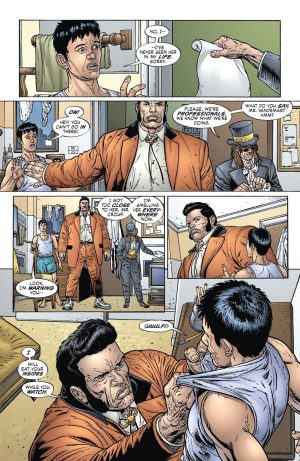

Gaiman having better things to do by now, the job of scripting the comic fell to Mike Carey, who at least has form in writing Gaiman’s characters. Carey’s main change is to replace Gaiman’s third-person narrative with a first-person account by the protagonist Richard (albeit one occasionally including scenes to which Richard was not witness and that he could not have been told about). Other than that, and making the Angel Islington male rather than neuter (arguably an error), Carey is, like the 2013 radio adaptation, pretty faithful to the structure of the original series. Some scenes are lost, with Gaiman’s rich epilogue particularly to be mourned, but the basic sequence of events remains untouched.

That does mean that the main problem of Gaiman’s story, that too many things happen merely because the plot needs them to happen, carries through. On the other hand, the overall attractiveness of Gaiman’s characters is also preserved, and Carey adds a couple of flourishes of his own. One endearing addition is the point where Richard is having the two Londons, London Above and Below, explained to him as London Above being a shadow of London Below. Surely, Richard says, it should be the other way around. No, he is told – London Above is too thin to cast shadows.

Glenn Fabry’s art is in some respects attractive and interesting. He has a clean line, and gives a sense of the culture of London Below by dressing many of the characters as if they have clothed themselves from a lost BBC costume store. The depiction of the mercurial and untrustworthy Marquis de Carabas as a literal black man echoes Michael Moorcock’s albino hero Jerry Cornelius, and is one of the more intriguing aspects of the visuals. On the other hand, the female characters are often depicted as scantily clad and in ways that emphasise their bodies. The lead female character, Door, is here a goth fetish model with an apparent disinterest in underwear, which sexualises the character in a way absent from any other version of Neverwhere. Carey at least has the grace to make a small plot point out of this, but it’s still a bit unpleasant. Also, nobody seems to have any shadows, and as a result characters look as if they have been layered over their backgrounds, rather than being integrated into them.

This isn’t a bad comic, by any means. But of all the various different versions of Neverwhere, this is the least essential.