Review by Ian Keogh

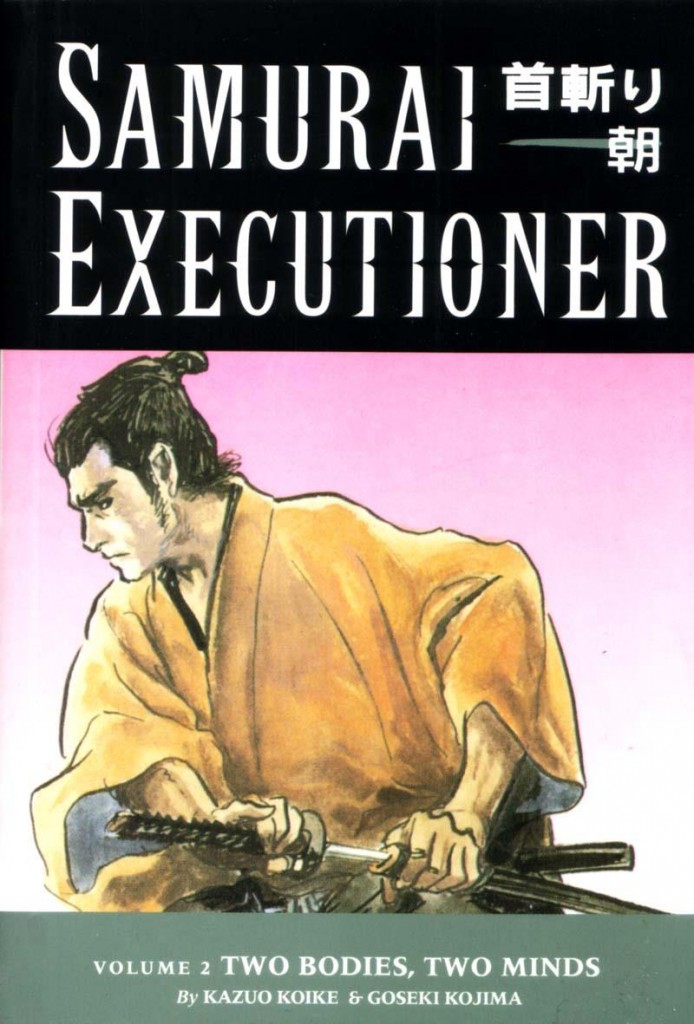

This features three further morality tales of master swordsman Yamada Asaemon, the Samurai Executioner of the title. There’s an admirably different tone to each of the stories here, the common thread being the deserving always meeting their end via the executioner’s sword.

O-Tsuya is a geisha girl and an arsonist, deriving no sexual pleasure whatsoever from standard encounters, but becoming intensely aroused by fire. The larger the conflagration, the greater the effect it has on her. Her story is followed by the conniving of a crooked businessman to save his rapist son, with Yamada taking a far greater part, and an angry woman tuning up on Yamada’s doorstep with a sure way of attracting attention.

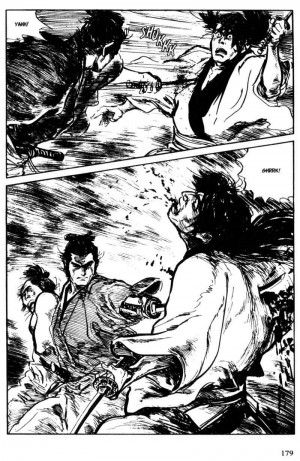

In the previous When the Demon Knife Weeps Kazuo Koike’s intensive research into Edo period Japan (1603-1868) manifested largely in social proprieties, but the topic of arson requires a rapid response from fireman in communities where houses are largely flammable, and the way Koike’s research merges with Goseki Kojima’s art is a brilliant display of function. Kojima is a frustrating artist. His action scenes are glorious, and his pages are wonderfully composed, but also characterised by smudgy work, some flat faces and a difficulty in distinguishing characters.

The assumed historical accuracy of Samurai Executioner results in some unpleasant attitudes by today’s standards. The inevitability of criminals eventually encountering the executioner himself won’t mitigate some explicit scenes of rape extended over several pages, which could be construed as of the having one’s cake and eating it variety. Yet the story following that opening is compelling, as Yamada out-manoeuvres a local businessman in terms of both protocol and swordsmanship. It’s the finest of three very good stories presented.

The final story also offers a disturbing (by modern day standards) insight into the application of the law in Edo Japan, where the interests of the more important were protected irrespective of any notions of right or wrong. The discussion of this is fascinating, but intrusive, Koike wanting to make his points at the cost of the story’s flow. It leads, however, to a brilliantly staged conclusion that’s as brutal and extended as the second chapter’s rape, but more understandable in context.

Japanese terminology abounds, and Dark Horse have kept these phrases intact, providing a glossary in preference to explaining them as they occur. It’s still an awkward mixture, and those unfamiliar with the Japanese culture of the period may find themselves losing track of the story as they follow one glossary explanation to the next.

It’s for Lone Wolf and Cub that Koike and Kojima are renowned, but parts of Samurai Executioner are equally brilliant. The blend of investigative depth and horrendous violence is difficult to resist. If preferred, this content is also available merged with the previous book and the the title story from the following The Hell Stick as Samurai Executioner Omnibus volume one.