Review by Frank Plowright

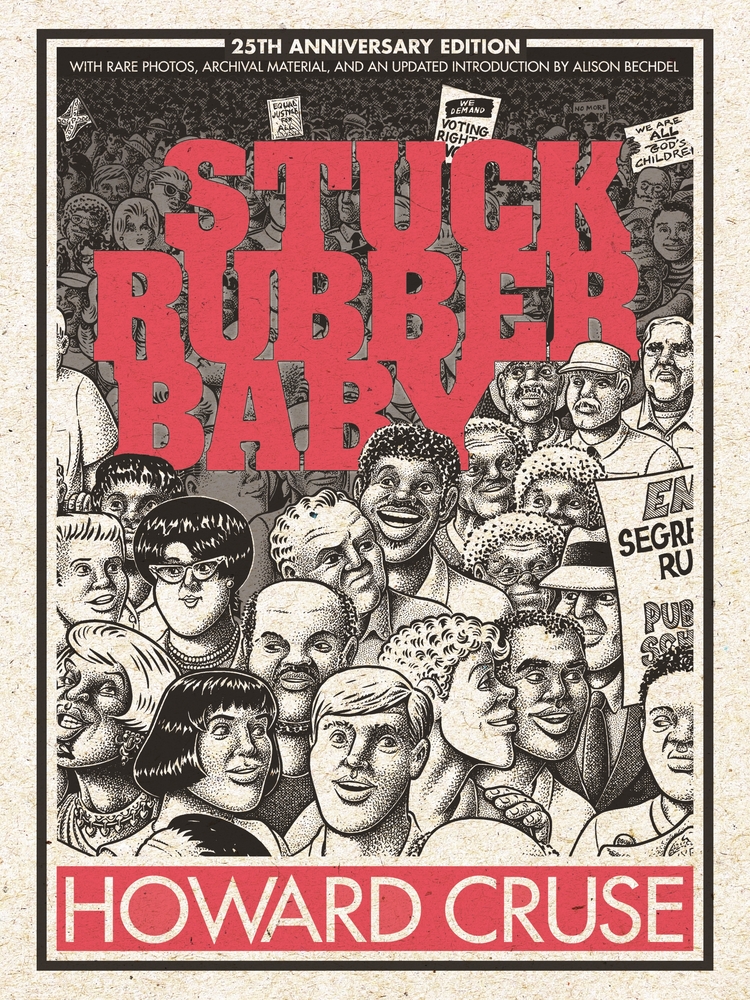

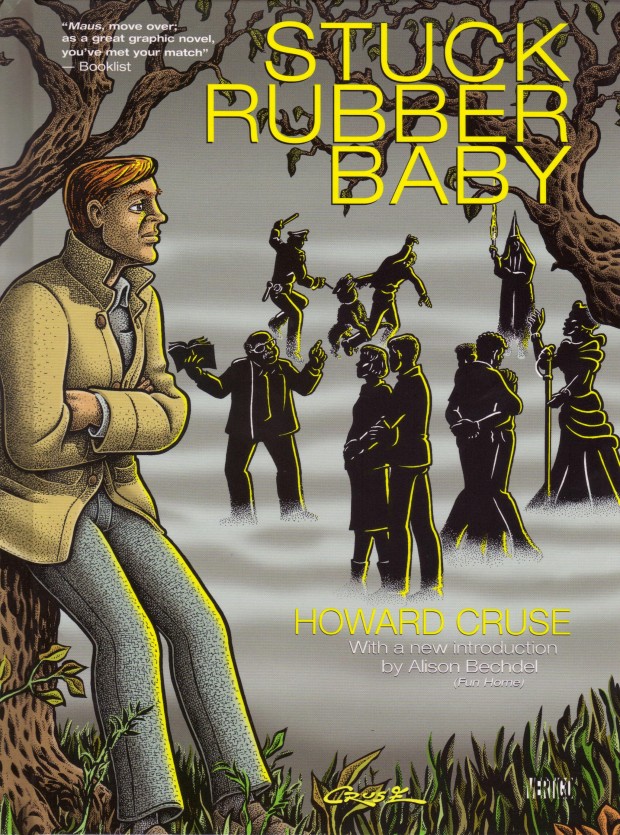

When first published in 1995, Stuck Rubber Baby accrued near universal acclaim. Comparisons were made with the best English language graphic novels, and not considered exaggeration, yet it’s drifted in and out of print. Maus and Watchmen still regularly top all-time best lists while Stuck Rubber Baby is absent. Perhaps a 25th anniversary edition with additional contextualising and background material will reinstate its reputation.

In the years since 1995 the world hasn’t been flooded with better semi-autobiographical coming of age graphic novels. There’s a case to be made for Epileptic or Fun Home, but Stuck Rubber Baby is every bit their equal despite the content not being one person’s experience. In his afterword Howard Cruse identifies Stuck Rubber Baby as fiction, while noting that anecdotes and incidents are informed by both his own experiences, particularly growing up in early 1960s Alabama, and those of friends.

The narrative voice is the middle-aged Toland Polk, now relatively content in a same sex relationship, reflecting on his formative years in the fictional Southern town of Clayfield. The narrator doesn’t spare his younger incarnation, laying bare self-obsession in the face of other people’s personal problems and the world’s wider issues. Polk is a confused teenager who gradually accepts he’s gay after a period of fighting it in order to conform. This strand alone is heartwarming and heartbreaking, but what elevates his story is linking it to the period’s growing social awareness and civil unrest.

The younger Polk is a passive character, perhaps not disengaged as Alison Bechdel would have it in her introduction to an earlier edition, but not one to place his head above the parapet either. He realises he’s gay very early on, but denies and represses this to maintain a distance from the problems it will bring. As with many, it takes a specific personal tragedy to awaken him and force the realisation that he has to accept who he is, and he has to commit to change.

While Polk is the focus, Cruse supplies a dense narrative, and many other cast members progress to a level of personal or civil understanding. This isn’t a hectoring process, but one of characters coming to terms with what they previously denied in a manner that never seems forced. The less sympathetic creations are those with bigoted views, but despite these being anathema to Cruse, if they have a significant part to play he never reduces them to caricature. This is key to why Stuck Rubber Baby is so compelling. Most cast members are inextricably linked to social issues, but were these all stripped out the remains would present a well-rounded and largely likeable, if flawed, set of characters.

Integral to this is Cruse’s art, which is as dense and detailed as his plot. He presents his story in an atmospheric deeply cross-hatched style, almost stippling the cast to death as the light plays off their features. He portrays people with chins on a Judge Dredd scale, but the compelling story absorbs that eccentricity. There are also interesting experiments: jagged layouts indicating conflict, and visually impressive panels presenting imagined scenes.

Is this all just preaching to the converted? One would hope not. While there’s been significant progress, for many teenagers affirming sexual orientation remains problematical due to parental, community or religious attitudes. It’s surely not possible to read Stuck Rubber Baby without considering the backdrop, and even the reader believing themselves informed and enlightened will discover something to ponder.