Review by Frank Plowright

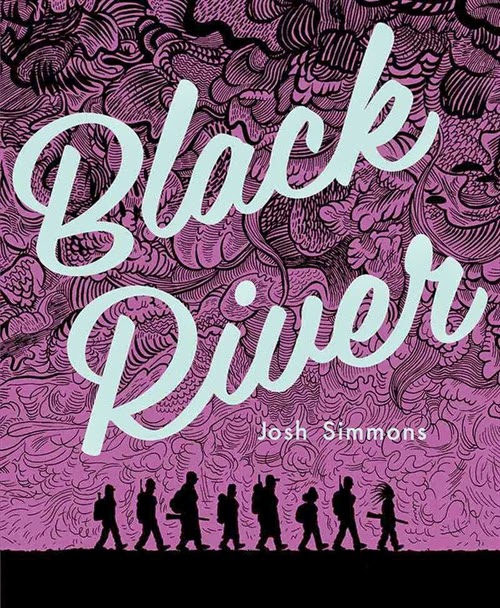

We’re never told how it happened, but in Josh Simmons’ desolate snapshot of the future, civilisation has disintegrated. Cities are shown still burning in the background and the world belongs to the strongest.

Our way into this horror is via a group of predominantly women travellers chancing on a stash of supplies in Alaska. The discovery of not only sustenance, but also indulgence is the most upbeat sequence of Black River, and the remainder is unrelentingly depressing without a sliver of hope or humour. The nearest comparison would be the nihilistic cartoons of Johnny Ryan transposed to a real world, where no law exists beyond might is right.

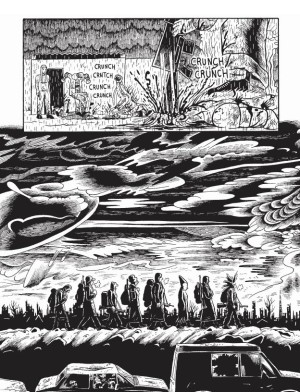

Life is brutal and cheap as humanity is reduced to predators and prey by need and lack of supply, and to accentuate the random occurrence of death or injury and the mundane existence, prolonged sequences are nothing but a plodding journey. These sacrifice the reader’s attention for verisimilitude.

A comedy club proves to be no such thing, except as an extremely black joke on Simmons’ part, and the entire middle section of the story is the women captured by a group of men. One of their captors prolongs their terror by keeping them bound and making no secret of their eventual purpose and fate. Some may interpret misogyny in the presentation, but that’s not a feature of Simmons’ other work, and Black River is centred within a fictional tradition of crumbling civilisation exacerbating humanity’s worst tendencies amid post-apocalyptic landscapes.

The artwork is as strange as the story, with the horrors on the surface contrasted by detailed and decorative skies. Intricate cloud patterns or the aurora borealis hover above carnage and wasteland, representing the beauty and unattainable freedom. In this detailed monochrome graphic novel black predominates, accentuating the gloom, but when it comes to the cast, Simmons’ artistic skills fail him. He supplies two basic facial expressions, the stoic and the wild-eyed loon, with the former predominant. It’s possibly intended as a form of passivity in adversity, but if so it works against the story he’s telling as it’s applied equally to the spotlighted cast and those they encounter.

Black River ends in strange fashion, with footsteps being erased, a commentary perhaps on how we’re drifting into and out of what’s torment ended only by death for those experiencing it.

The biggest problem with Black River is that Simmons raises so few issues, and all are explored within The Walking Dead, where the writing is better and the art is better. Additionally, for those to whom it matters, The Walking Dead offers interludes of hope among the horror. A strength of a graphic novel with intent beyond two super-powered characters pummelling each other is surely whether it will be read a second time. With Black River that’s unlikely.