Review by Frank Plowright

Having taken his central plot idea from The Bourne Identity, Jean Van Hamme has twisted and folded it back in a manner every bit as artful as Robert Ludlum, and now he throws in another spanner.

While he retains no memory, XIII is at least convinced by the evidence that he’s actually Jason McLane. There is, however, a six year gap in McLane’s past when it’s assumed he was working for the CIA, but can anyone really be sure? The only certainty is that sometime during those six years he learned to speak Spanish. This is all knowledge that’s seeped into slightly wider circulation.

Thirteen to One was another volume in which some questions were answered, but at a cost. It’s proved extremely advisable that XIII and Agent Jones disappear, and luckily they have a friend with vast land holdings and a sense of discretion. Nothing ever remains static and simple for McLane, though, and in quick succession he learns that he apparently has a wife, she’s the leader of guerilla freedom fighters in Costa Verde, and she’s been captured, imprisoned and is awaiting execution. Oh, and by the end of the book it appears XIII has yet another identity to contend with. Or possibly two.

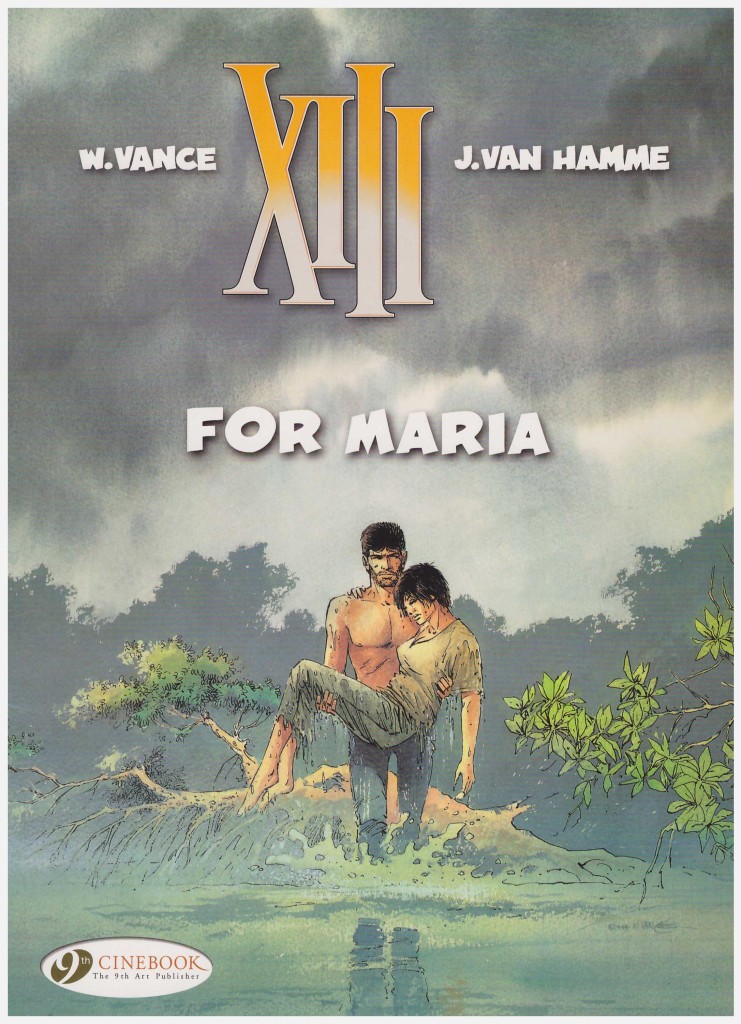

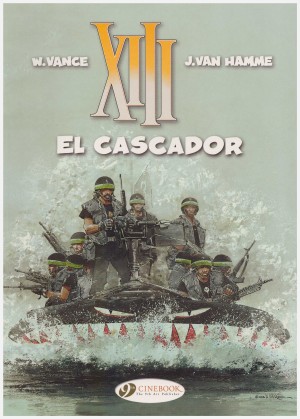

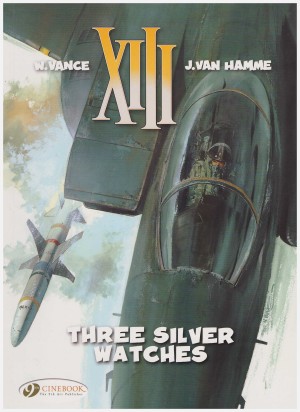

For Maria and its continuations El Cascador and Three Silver Watches are Van Hamme shifting tone a little. We’re still very much in action thriller mode, but now in a small Latin American country struggling to overthrow a dictator. There’s a considerable amount of set-up and exposition required to make the next portion work, and it slows For Maria down, but that’s a price worth paying unless your intention is to buy this book and this book alone. Van Hamme surprises with a previously seen character recurring, and he introduces a sound variation on the archetype of the Latin American priest who sees no contradiction between his faith and engaging in revolutionary activity.

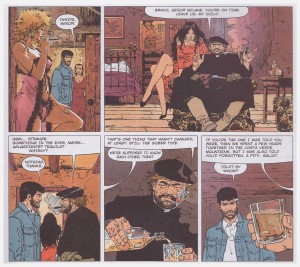

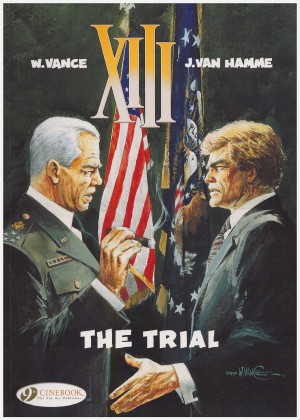

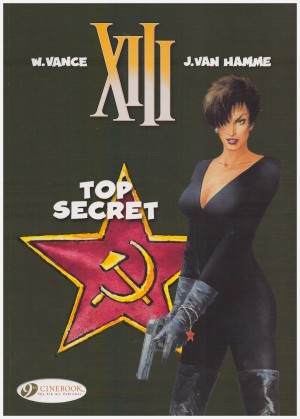

William Vance’s cover is somewhat misleading, although to say how would drop into spoiler territory, but his internal artwork is the superbly disciplined storytelling we’ve come to expect. There’s a largish cast, all well distinguished, and Vance is the master of illustrating Van Hamme’s lengthy conversations. Towards the end of the book there’s a two page conversation extending over nineteen panels. There’s one wordless panel among the first fifteen, and in all but one of the remainder twenty words is the lower end of the scale. Vance varies his angles, his distance and his backgrounds to ensure a visual appeal. If that weren’t enough, as the conversation occurs in the Presidential palace, those backgrounds are plastered with faux oil paintings. It’s another spectacular example of what can be achieved when an artist is permitted a year to illustrate 46 pages.